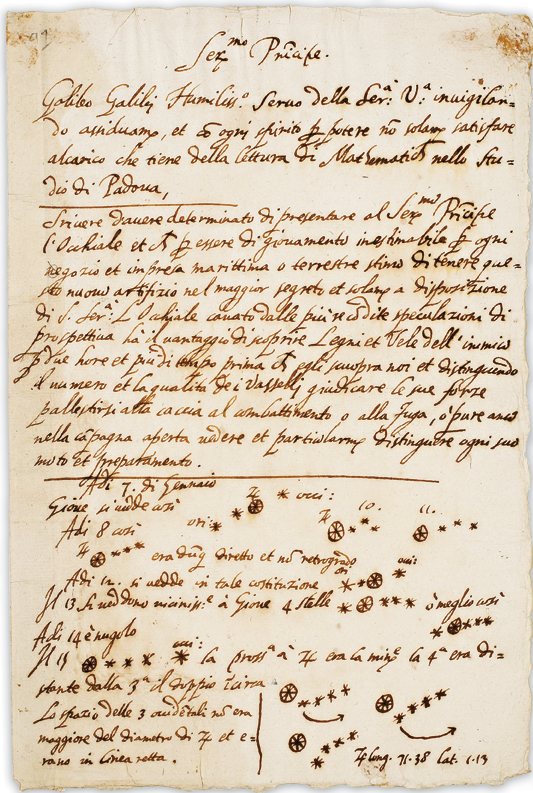

On Jan. 7, 1610, Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei peered through his newly improved 20-power homemade telescope at the planet Jupiter. He noticed three other points of light near the planet, at first believing them to be distant stars. Observing them over several nights, he noted that they appeared to move in the wrong direction with regard to the background stars and they remained in Jupiter's proximity but changed their positions relative to one another. Four days later, he observed a fourth point of light near the planet with the same unusual behavior. By Jan. 15, Galileo correctly concluded that he had discovered four moons orbiting around Jupiter, providing strong evidence for the Copernican theory that most celestial objects did not revolve around the Earth.

In March 1610, Galileo published his discoveries of Jupiter's satellites and other celestial observations in a book titled Siderius Nuncius (The Starry Messenger). As their discoverer, Galileo had naming rights to Jupiter's satellites. He proposed to name them after his patrons the Medicis and astronomers called them the Medicean Stars through much of the seventeenth century, although in his own notes Galileo referred to them by the Roman numerals I, II, III, and IV, in order of their distance from Jupiter. Astronomers still refer to the four moons as the Galilean satellites in honor of their discoverer.

In 1614, the German astronomer Johannes Kepler suggested naming the satellites after mythological figures associated with Jupiter, namely Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, but his idea didn't catch on for more than 200 years. Scientists didn't discover any more satellites around Jupiter until 1892 when American astronomer E.E. Barnard found Jupiter's fifth moon Amalthea, much smaller than the Galilean moons and orbiting closer to the planet than Io. It was the last satellite in the solar system found by visual observation - all subsequent discoveries occurred via photography or digital imaging. As of today, astronomers have identified 95 moons orbiting Jupiter.

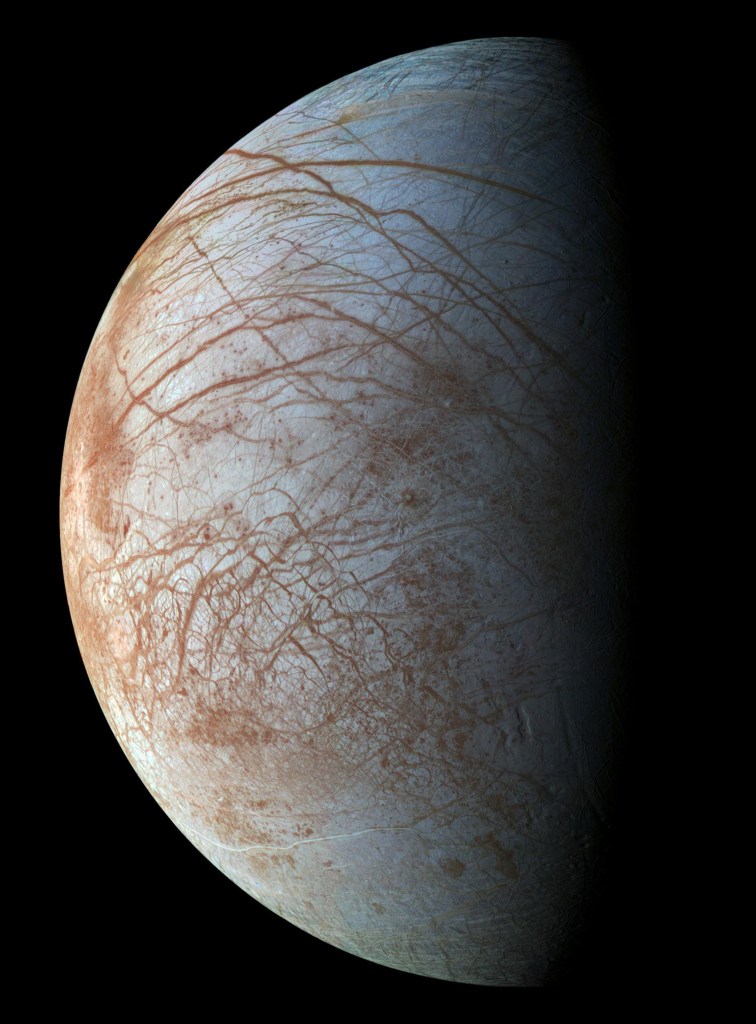

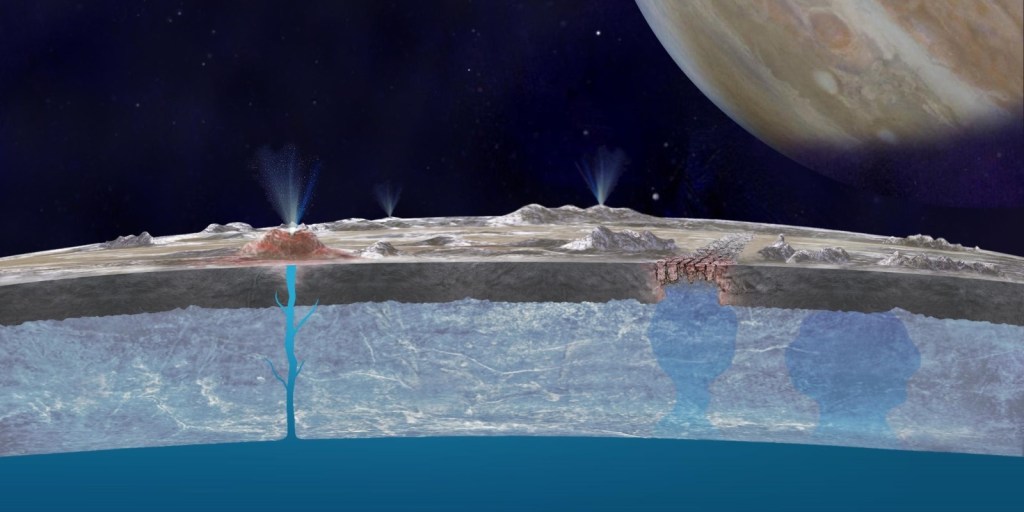

Although each of the Galilean satellites has unique features, such as the volcanoes of Io, the heavily cratered surface of Callisto, and the magnetic field of Ganymede, scientists have focused more attention on Europa due to the tantalizing possibility that it might be hospitable to life. In the 1970s, NASA's Pioneer 10 and 11 and Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft took ever increasingly detailed images of the large satellites including Europa during their flybys of Jupiter. The photographs revealed Europa to have the smoothest surface of any object in the solar system, indicating a relatively young crust, and also one of the brightest of any satellite indicating a highly reflective surface. These features led scientists to hypothesize that Europa is covered by an icy crust floating on a subsurface salty ocean. They further postulated that tidal heating caused by Jupiter's gravity reforms the surface ice layer in cycles of melting and freezing.

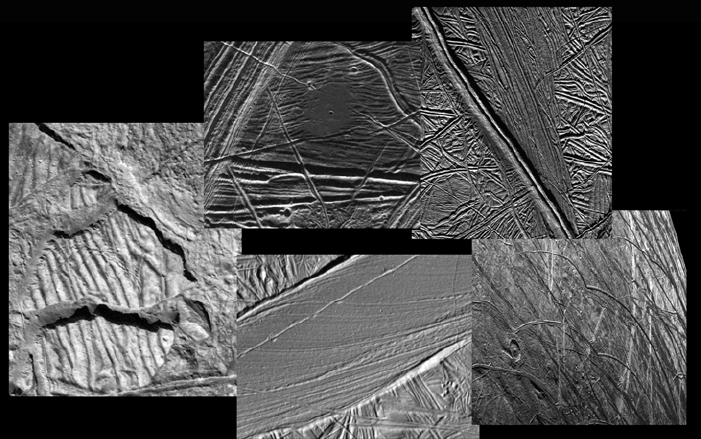

More detailed observations from NASA's Galileo spacecraft that orbited Jupiter between 1995 and 2003 and completed 11 close encounters with Europa revealed that long linear features on its surface may indicate tidal or tectonic activity. Reddish-brown material along the fissures and in splotches elsewhere on the surface may contain salts and sulfur compounds transported from below the crust and modified by radiation. Observations from the Hubble Space Telescope and re-analysis of images from Galileo revealed possible plumes emanating from beneath Europa's crust, lending credence to that hypothesis. While the exact composition of this material is not known, it likely holds clues to whether Europa may be hospitable to life.

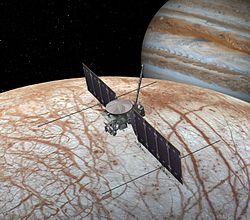

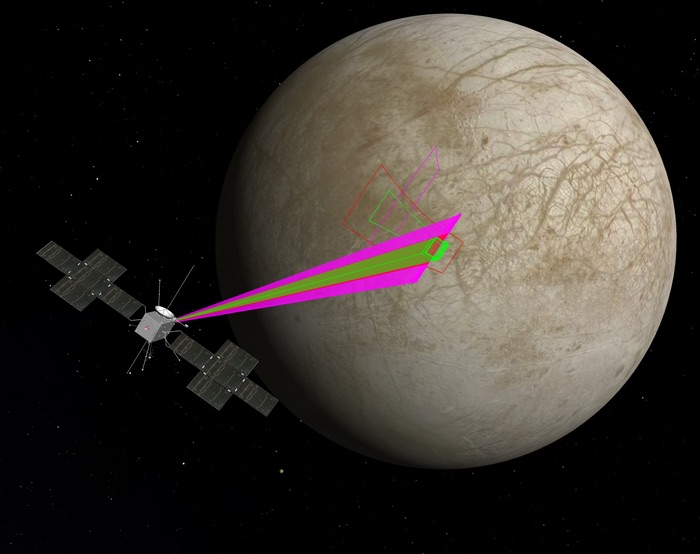

Future robotic explorers of Europa may answer some of the outstanding questions about this unique satellite of Jupiter. NASA's Europa Clipper set off in October 2024 on a 5.5-year journey to Jupiter. After its arrival in 2030, the spacecraft will enter orbit around the giant planet and conduct 49 flybys of Europa during its four-year mission. Managed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, and the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, Europa Clipper will carry nine instruments including imaging systems and a radar to better understand the structure of the icy crust. Data from Europa Clipper will complement information returned by the European Space Agency's JUICE (Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer) spacecraft. Launched in April 2023, JUICE will first enter orbit around Jupiter in 2031 and then enter orbit around Ganymede in 2034. The spacecraft also plans to conduct studies of Europa complementary with Europa Clipper's. The two spacecraft should greatly increase our understanding of Europa and perhaps uncover new mysteries.