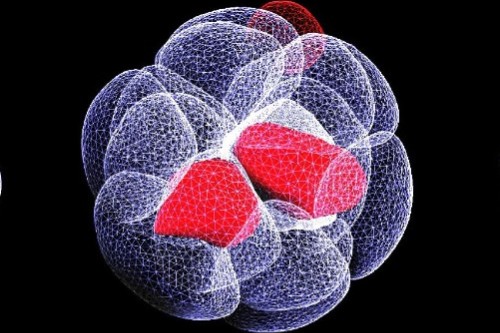

Image, which was not part of this study, shows the developing embryo of a small mammal.Dr M. Zernicka-Goetz, Gurdon Institute: Wellcome Collection

A study has shown that a dangerous game of 'brinkmanship' between rival genes in mammals could help explain why many fertilised eggs don't result in a new life.

Within the genome genes can be in conflict, where opposing chromosomes act in their own evolutionary interest. Although this tussle between male and female genes is commonly understood, what determines the winner – or if there even is one – has long proven elusive.

Biologists from the University of Bristol and University of Exeter have demonstrated that a dangerous game of 'brinkmanship' could provide the answer, where the stakes are increasingly raised resulting in either the boldest being triumphant or mutual self-destruction.

Co-lead author Dr Patrick Kennedy, Lecturer in Biological Sciences at the University of Bristol, said: "In many mammals, it is known that genes from each parent find themselves in a tug of war over the traits shown by the offspring.

"Our findings show the triumphant genes are those which keep upping the ante, prompting their adversary to back down and surrender, similar to the Cold War military strategy of brinkmanship. But if both genes take it too far to breaking point, they could ultimately perish."

The researchers used a combination of evolutionary theory and computational simulations to explore strategies deployed by genes during risky negotiations. In their models, genes could invest different amounts in the conflict depending on whether they are from the male or female. Their findings showed that if both parties invested too much, and ultimately tipped over the edge, the body they are in might not survive at all.

Their published theory suggests that, in a high-stakes game between selfish genes, the winning genes are those prepared to step closer towards the brink, deterring counteraction by rivals.

When genes in the same genome act differently depending on whether they came from the male or female, biologists say there is "genomic imprinting" – a process of rival chromosomes acting in their own evolutionary interest. Although imprinting conflicts are now well-known, predicting which side wins has puzzled scientists.

Dr Kennedy explained: "In the foetus's genome, genes from the male can evolve to try to make the foetus greedier – grabbing more resources from the female. Meanwhile, genes from females try to resist. Biologists think this struggle is risky: the more each set of chromosomes tries get its own way, the greater the risk to the foetus's growth and survival.

"After the Cuban missile crisis, the Nobel Prize winning game theorist Thomas Schelling coined a famous metaphor for brinkmanship, which also captures the genetic forces at play in our model. Imagine two mountaineers, roped together and arguing. To get the other to give up, each climber can step closer towards a crumbling cliff edge, increasing the risk that they both slip into the abyss."

Co-lead author Dr Andy Higginson, Senior Lecturer in the Centre for Research in Animal Behaviour at the University of Exeter, added: "Our results have some surprising implications. Developmental events like early pregnancy loss, could be the products of disputes between genes that have evolved to go to the brink in attempts to coerce other genes into letting them win. This increasingly dangerous conflict between genes could affect why around one in four fertilised eggs never develop past the first trimester.

"Our model suggests that Schelling's mountaineers are not only found in Cold War nuclear threats but also in the genome itself."

Paper:

'Brinkmanship in intragenomic conflict' by P. Kennedy and A.D. Higginson, A. D. in Proceedings of the Royal Society B