A new genetic mutation behind childhood glaucoma has been identified by a team of international researchers, including from Flinders University.

The research found through DNA sequencing and further testing that a genetic mutation in the THBS1 gene led to the development of severe childhood glaucoma.

The discovery may improve disease screening and personalise treatments, says the team led by the Massachusetts Eye and Ear at Harvard University and other experts.

Together they discovered a new genetic mutation that may be a root cause of severe cases of childhood glaucoma, a devastating condition that runs in families and can rob children of their vision by 3 years of age.

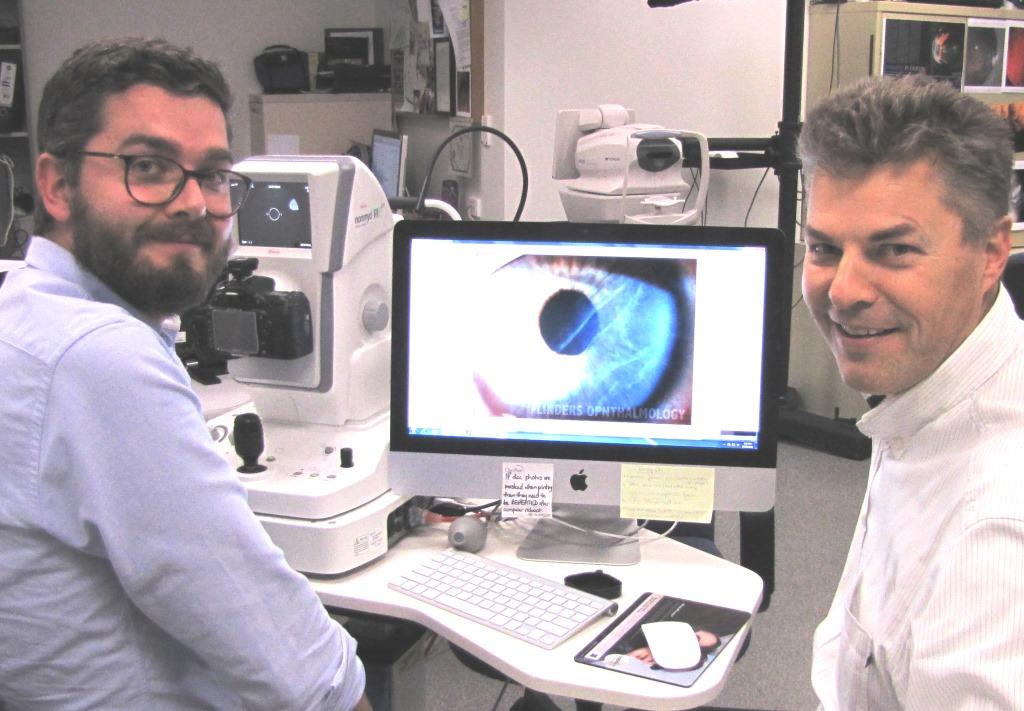

Through advanced genome-sequencing technology, led in part by Flinders University and other Australian ophthalmology experts, the researchers found a mutation in the thrombospondin-1 (THBS1) gene in three ethnically and geographically diverse families with childhood glaucoma histories.

The researchers then confirmed their findings in a mouse model that possessed the genetic mutation and went on to develop symptoms of glaucoma driven by a previously unknown disease mechanism.

The new findings, published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, could lead to improved screening for childhood glaucoma and earlier and more targeted treatments to prevent vision loss in children with the mutation, according to the study's authors.

"This is a very exciting finding for families affected by childhood glaucoma," said Janey L. Wiggs, MD, PhD, Associate Chief of Ophthalmology Clinical Research at Mass Eye and Ear and the Vice Chair for Ophthalmology Clinical Research and Paul Austin Chandler Professor of Ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School.

"With this new knowledge, we can offer genetic testing to identify children in a family who may be at risk for the disease and start disease surveillance and conventional treatments earlier to preserve their vision. In the future, we would look to develop new therapies to target this genetic mutation."

Childhood, or congenital, glaucoma is a rare but serious disease that presents in children as early as birth and as late as 3 years of age. Despite its rarity, childhood glaucoma is responsible for 5 percent of cases of child blindness worldwide.

When this research began 30 years ago, scientists were only able to identify regions of the genome affected in glaucoma. Thanks to advances in genomic technology, researchers gained the ability to review the complete genetic makeup of individuals with and without glaucoma to determine which specific genetic mutations play a role in the disease.

Later collaborations with colleagues at Flinders University in Australia sought further evidence of any childhood glaucoma families with thrombospondin mutations.

This was the first time that researchers identified this kind of disease mechanism for causing childhood glaucoma.

"This work highlights the power of international collaborations," says study co-author Flinders University Associate Professor Owen Siggs, also the Garvan Institute of Medical Research. "There's such incredible genetic diversity across the globe, and comparing this information is becoming more and more critical for discoveries like this."

Flinders University coauthor, PhD Lachlan Wheelhouse Knight says with about 1 in 30,000 born with the condition in Australia and other largely European countries, the international collaboration means more individuals can be captured in the data collaboration.

"This research continues to increase our understanding of childhood glaucoma genetics," he says.

The researchers will also continue to look for new genes associated with childhood glaucoma in the hopes of one day developing very comprehensive screening.

The article, Thrombospondin-1 missense alleles induce extracellular matrix protein aggregation and trabecular meshwork dysfunction in congenital glaucoma (2022), by H Fu, OM Siggs, LSW Knight, SE Staffieri, JB Ruddle, AE Birsner, ER Collantes, JE Craig, JL Wiggs and RJ D'Amato has been published in JCI, The Journal of Clinical Investigation. DOI: 10.1172/JCI156967.

This study was funded by the March of Dimes foundation, US NIH (grants R01EY031820 and P30EY014104), the Ophthalmic Research Institute of Australia, the Channel 7 Children's Research Foundation, Department of Innovation, Industry, Science and Research and Australia's National Health and Medical Research Council.