Wanting to explore the Antarctic in 1908 could have been thought of as a form of madness.

When famed explorer and University graduate, Sir Douglas Mawson, with team mate Alistair Mackey, set out to be the first to reach the magnetic South Pole, it meant bodily dragging their supply sleds almost 2000 kilometres across a treacherous, snow-covered landscape.

An earlier explorer had described how the extreme Antarctic cold had killed the nerves in his teeth which then began to crack; a confronting idea for anyone. Mawson and Mackey were 35 at the time, and this environment pushed them to their limits.

So consider the other member of the team who was nearly 50 at the time. His name was Sir Tannatt Edgeworth David, and he was a Professor of Geology at the University of Sydney.

Exploring land and sea

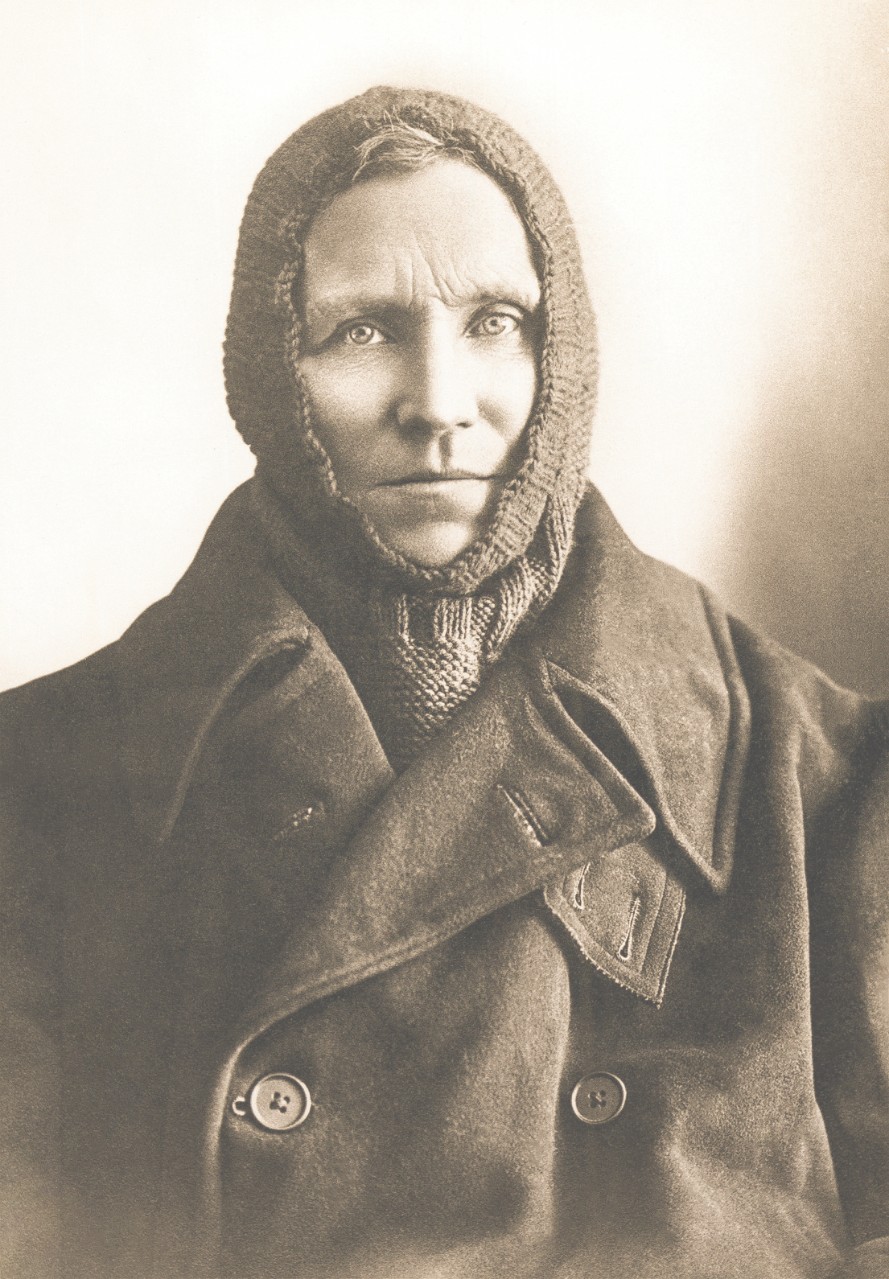

Professor Tannatt Edgeworth David in 1909, just after his historymaking Antarctic ordeal. Photo: University Archives (G3_224_1206).

David had been Mawson's geology lecturer and mentor at the University, and Mawson recommended he be one of the team leaders in the multi-team Antarctic expedition being organised by that other renowned explorer, Ernest Shackleton.

David was already a household name in Australia for identifying the Greta coal seam which became the motherlode of the Hunter Valley coal industry, setting New South Wales on a path to previously unimagined prosperity.

Talking about it at public meetings, David demonstrated he was a compelling speaker with great charm, intelligence and humour. His fame grew, as did his capacity to fundraise for his projects, including the Shackleton expedition - part of the reason Shackleton included him.

Born in Wales, David first came to Australia in his early 20s to recover from a nervous breakdown likely caused by the loss of his Christian faith; a tricky situation in a deeply religious era, especially when his father was an admired reverend who expected David would take holy orders.

Returning to the UK still faithless, David pursued a longstanding interest in geology and quickly began producing learned papers that impressed the geological academic community.

Meanwhile in New South Wales, the job of Assistant Geological Surveyor to the NSW Government became available and David returned to Australia take it. This led him to identifying the Hunter Valley coal seam, putting him in good stead to apply for the chair of geology and palaeontology when it came up in 1891 at the University of Sydney.

A subsequent mining boom allowed David to convince the University that it needed a school of mines, and soon his one man geology department in a shabby cottage became a new building and a lecture hall with a growing number of students.

More international attention came to David as he led a team to Funafuti Atoll, in the central western Pacific, to deepdrill for evidence to prove a theory about how reefs were formed. Two previous teams, including one from the Royal Society of London, had had failed the drill attempt, spurring David on. With the world watching, his attempt was a spectacular success, though the reef evidence uncovered was inconclusive.

David, with shouldered pick, and assistant Jack Rourke in 1886, having uncovered the Greta Coal Seam in Swamp (Deep) Creek near Abermain. Photo: University Archives (G3_224_1589).

Geological warfare

Returning to the University, David's already immense popularity grew, with students fondly calling him "The Prof". But with the start of World War I, David had an audacious idea. He convinced the government to let him lead a team of Australian geologists and miners to France and the Western Front, which he did in 1915. He was 58 at the time.

The specialised knowledge of David's team, the so-called Australian Mining Corps, led to pioneering thinking on how to place and dig trenches and deal with ground water. But David had come with another, much bigger idea.

His plan was to dig tunnels under the German lines on the Messines- Wytchaete Ridge, fill them with TNT and detonate them. Which he did spectacularly in 1917, changing the course of the battle.

Tannatt Edgeworth David died in Sydney in 1934, aged 76, after being Professor of Geology at the University of Sydney for 35 years.

Unheard of for a lowly geologist, he was given a State Funeral and thousands crowded the streets to farewell a person of truly heroic stature.

Written by George Dodd for the Sydney Alumni Magazine, with thanks to Professor Maxwell Bennett AO.