Old convict records and today's digital technologies have come together in a world-first memorial in the Hobart Pententiary, launched on November 29.

The Unshackled memorial, the brainchild of UNE historian Professor Hamish Maxwell-Stewart, allows visitors to tap into the records of 75,000 convicts shipped to Van Diemens Land over 50 years.

Curious visitors can now use smartphones to tap into two million records from a wide range of sources to look "not just down the grain of a person's life, but at their connections to other people and places throughout their lives", Prof. Maxwell-Stewart said.

The information produced by a visitor enquiry appears on a digitised memorial pillar suspended from the Penitentiary chapel roof. Over four minutes, slowly progressing around the pillar's four sides, information appears about the convict's crime and sentence, their voyage to the penal colony, and what the records say about their lives in Van Diemens Land.

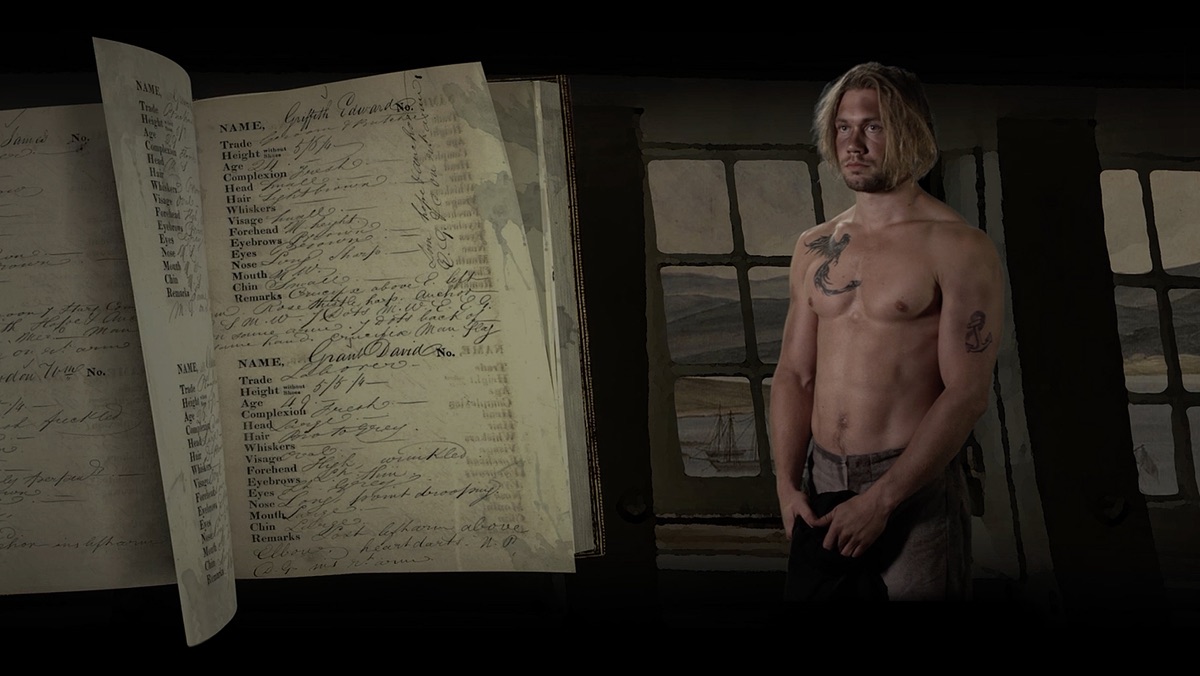

About 1000 AI-generated avatars of real convicts, based on prison records, have been generated. Many more are to come, as a way of humanising people aged from 10-80 who were shipped to the island from more than 50 countries.

Above: Convict record of Edward Griffiths, and digital avatar made from descriptions of physique and tattoos.

"Tasmania has digitised a greater proportion of its archive than any other Australian state or territory," Prof. Maxwell-Stewart said.

"Thanks to Tasmanian Government funding, that data has now been spun into something quite magical." The Government put $1.25 million towards the project.

Prof. Maxwell-Stewart anticipates this is just the beginning of how old records, digital tech, smartphones and people's undying curiosity about convict ancestors will be used.

With a $540,000 Australian Research Council grant awarded to the National Trust Tasmania and partners, UNE and Monash University, the project team intend to expand the digital project across old convict-frequented sites through Tasmania.

In future, he says, he hopes that visitors who agree to have their phone tagged will be able to visit other convict sites around Tasmania and be automatically shown whatever information the records can reveal about the convict they are interested in.

Because the records extend into post-convict civic life, old pubs and other heritage buildings are interested in tapping into the same digital network. A modern visitor will be able to have an uncanny insight into the places their ancestor frequented, as a convict and afterwards.

"There's the potential to create a tailored experience for visitors that draws on a real curated dataset, but presents that information in new and unusual ways," Prof. Maxwell-Stewart said. "It's totally unique."

He also notes that the reliability of AI is often questionable because it scrapes data from the internet. The digital work being done in Tasmania is drawn from robust, curated records.

The 75,000 convicts (male and female) transported to Van Diemen's Land from 1803 to 1853 represented about 47% of the approximately 160,000 convicts transported to Australia.

More than 20% of Australians and 74% of Tasmanians are descended from convicts.