A microbe that breaks down a key digestive enzyme in the large intestine of humans and mice has been identified by RIKEN biologists1. This finding could eventually lead to the development of probiotics that can help restore balance to people who have too much of the enzyme in their large intestines.

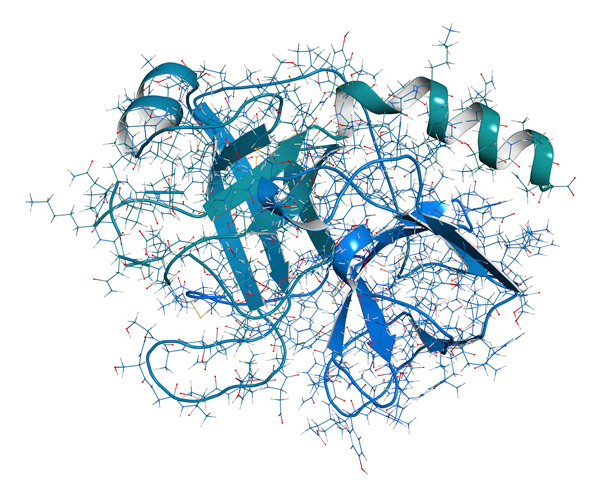

An enzyme known as trypsin (Fig. 1) helps us to digest food by chopping up proteins in the small intestine. But high levels of trypsin further down the digestive tract in the large intestine can be problematic, potentially leading to complications such as inflammatory bowel disease.

The interaction between digestive enzymes such as trypsin and the 10 trillion or so microbes that inhabit the human gut is highly complex. These gut bacteria belong to somewhere between 500 and 1,000 species in any individual, and it is fiendishly difficult to untangle the roles that individual species play in the gut.

"To isolate and culture the gut microbes outside the body is often challenging, especially since most of them are sensitive to oxygen," says Youxian Li of the RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences (IMS). "To establish a causal relationship between a microbe and a change in our body is even more difficult."

Figure 1: The molecular structure of trypsin, an important digestive enzyme for breaking down proteins. RIKEN researchers have discovered a gut microbe that can degrade trypsin, and which thus may help to keep trypsin levels in check in the large intestine, where the enzyme can cause problems. © MOLEKUUL/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Now, a team led by Kenya Honda of IMS has succeeded in establishing that a species known as Paraprevotella clara degrades trypsin in the large intestine and thus could play a major role in keeping trypsin levels in check in this region of the gut.

The rod-shaped bacterium was first isolated from human feces in 2009 by researchers at the Japanese probiotic company Yakult, but there was nothing to indicate its role in breaking down trypsin. "There was no indication that this species was special," notes Li.

The team went further and showed that P. clara's ability to degrade trypsin provided mice with added protection against intestinal infection by mouse hepatitis virus type 2 (MHV-2), a coronavirus that needs trypsin to gain entry into cells.

"We found that mice with low levels of trypsin in the large intestine were protected from infection when the virus was applied through the gastrointestinal route-more of them survived and they had less dissemination of viral particles in other organs," explains Li. "So this indicates that having trypsin-disintegrating species in the large intestine is probably protective when it comes to intestinal infections by viruses that depend on trypsin."

This opens up new avenues of research. "We now have a tool we can apply to different kinds of intestinal disease models to see if trypsin plays a role in various diseases," says Li.