A hundred years ago, the Ukrainian author Isaac Babel wrote about grotesque acts of violence in the Polish-Soviet war. Today, authors like Babel are important when a new war rages in the same region.

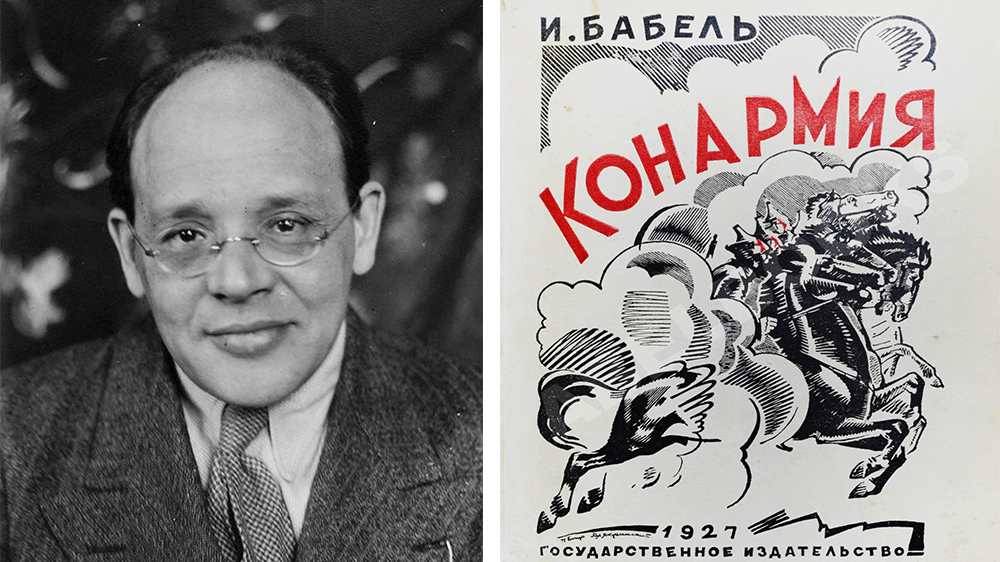

NEW RELEVANCE: "Isaac Babel's descriptions of the conflicts between Russians, Ukrainians, Poles and Jews during the violent upheavals of the last century are as disturbing today as they were when first published," says Professor of Polish, Knut Andreas Grimstad. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Isaak Babel is best known in Norway for his collection of short stories called "Odesa Stories", a realistic but also humorous and exotic depiction of the underworld in the city of Odesa, where Babel grew up.

However, it is "Red Cavalry", about the Polish-Soviet war in 1920, that has remained Babel's most famous work, according to Professor of Polish Knut Andreas Grimstad at the University of Oslo.

This collection of short stories is inspired by Babel's experiences as a war reporter. Many of the battles were fought in western Ukraine, in the region of Galicja.

"Babel's credible, explicit depictions of the increasingly grotesque acts of violence differed greatly from the revolutionary propaganda of the time. This was the first time many Russian readers were exposed to the realities of the war," Grimstad says.

In the West, Babel was known by many as the Soviet Hemingway. Hemingway himself, who always was on the lookout for a good story, admired Babel's writing, and after reading "Red Cavalry" he stated: "Babel's style is even more concise than mine".

Longing to gain acceptance

In the article "En "jødebolsjevik" rapporterer fra Ukraina: Isaak Babels mangfoldige minoritetsspråk" (A 'Commie Jew' Reports from Ukraine: Isaak Babel's Diverse Minority Idiom), which is published in the journal "Norsk litteraturvitenskapelig tidsskrift", Grimstad takes a closer look at what characterises Isaac Babel and his short stories in Red Cavalry.

Babel was born in a poor district of Odesa in 1894 when the Ukrainian city was still part of the Russian Empire. He grew up in a Jewish, Russified middle-class family.

Right from the start, he wrote about Jews with cleverness, humour and warmth, but according to Grimstad, he probably identified most with being an 'Odesite'.

"Like most Jews with experience from Russian schools, literary and social circles, Babel longed to gain acceptance, and he got it, not as an advocate for Judaism, but as a kindred spirit who had faith in Pushkin and the Russian cultural canon, as well as in the Revolution," Grimstad says.

Alexander Pushkin is considered by many to be the greatest Russian poet and holds the position of Russia's national poet.

Followed the Red Army as a reporter

At the beginning of the 1900s, the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party was split in two, and the Bolsheviks formed the radical wing. They were led by Vladimir Lenin and later called themselves Communists.

During the October Revolution of 1917, they seized power and established a new state power in Russia. The Communists wanted to spread their ideology around the world, and Poland was the place they wanted to start.

This led to the Polish-Soviet War, in which Babel was a war reporter. Under the alias Kirill Vasilyevich Lyutov, he followed the Bolshevik Cossack cavalry divisions through hard-hit villages in eastern Poland and western Ukraine.

According to Grimstad, his short stories express the identity conflict that Babel found himself in.

"On the one side is the Jew, who has joined the Russian Revolution and is now recording all the heinous acts that are being committed against the Jews and their Galicja culture. On the other side is the Bolshevik-literary stylist, who is never entirely comfortable with Bolshevism and Russia's increasing demands to be uncompromisingly unambiguous."

A fluid public self-image

According to Grimstad, Babel's writing is far from unambiguous. He has a job to do as a war reporter, but he is the total opposite of the archetypal macho soldiers with big, bushy moustaches he accompanies.

"We can imagine Babel as a small, frail intellectual with glasses. He was a feminine and delicate figure. For him, it was about gaining acceptance and approval. In Red Cavalry, he describes the resulting dilemma; among other things, he writes about a test of manhood in which he must crush a goose's head with his foot," Grimstad says.

In the opening short story called Crossing the Zbruch, Babel describes the heroic strength of the Cossacks, but also the suffering experienced by the Jews:

(I) find two ransacked wardrobes, scraps of women's fur coats on the floor, human excrement and shards of the sacred plate that Jews use once a year - on Passover.

"Babel often distances himself from his Jewish past, but not in the opening short story. In my opinion, one can say that Babel moves into and out of a Bolshevik identity. He portrays a fluid public self-image that never takes hold," Grimstad says.

Executed at the age of 45

The demand to write unambiguously became stronger and stronger in Russia, which didn't suit Isaac Babel. In 1932, under Stalin's rule, an ideologically based way of writing was introduced as dogma, and it meant that different ways of writing were forbidden.

"Unfortunately for Babel, everything in the Soviet Union under Stalin's rule was political and muscular. Furthermore, the problem wasn't just that Babel's stylistic taste was politically vague, but he was also nondescript with regard to ethnic and gender stereotypes," Grimstad says.

In Babel's Red Army prose, he blurs the boundaries between what is dominantly masculine and submissively feminine. The former is primarily associated with the bravery of the Cossacks and Bolsheviks, while the latter is associated with the Jewish and Polish.

These fluid boundaries that characterised many of Babel's stories throughout the 1930s eventually became too much for the Soviet establishment. Babel was imprisoned by the Soviet authorities in 1939, accused of anti-Soviet activities and executed the day after his arrest, at the age of 45.

One of the most famous Ukrainian authors

Russia did not succeed in subjugating Poland in 1920. Still, Isaac Babel did go down in history as one of the most famous Jewish-Ukrainian authors, along with names like Sholem Aleichem, the man behind the story in the musical "Fiddler on the Roof".

Now that Ukraine once again finds itself at war, it is especially important for the Ukrainian people to express their own culture - even though Babel once saw himself as a Soviet citizen, Grimstad points out.

"If you were born and raised in what is now Ukraine, you are Ukrainian. The borders and the people who live in these areas have been at the whim of others for several centuries."

"Telling a broader truth than the official one can have its price, and this was also the case when the Soviet Union was emerging: after Babel was executed, he was banned, and it was not until 1954 that he was cleared of all wrongdoing. Readers could once again experience the irrational brutality depicted in his texts," Grimstad says.