This article was published in the Autumn 2024 issue of Litterae Populi. The full issue can be found here.

Much of bear ecology remains unclear. On the Shiretoko Peninsula, a UNESCO World Natural Heritage site, researchers from Hokkaido University are conducting ongoing studies on the ecology of brown bears, including on what they eat and how to identify individual animals. What do these researchers aim to discover through their work?

Bounties of mountain and sea sustaining the lives of brown bears

The Shiretoko Peninsula in northeastern Hokkaido, a UNESCO World Natural Heritage site, is home to an estimated 500 brown bears, one of the highest densities of brown bears in the world. These bears thrive on the abundant food sources provided by mountains and the sea. The Rusha area, at the northern tip of the peninsula, is particularly significant for its river mouths, where pink salmon and chum salmon ascend to spawn, creating a high-density habitat of brown bears. Associate Professor Michito Shimozuru of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine has conducted various studies in the Rusha area for about 15 years, shedding light on the ecology of brown bears.

Associate Professor Michito Shimozuru conducts research on brown bear ecology (Photo by Associate Professor Shimozuru Michito)

Associate Professor Shimozuru's research group spent roughly seven years from 2012 studying the diet of brown bears in the Rusha area by collecting droppings and observing bear behavior. From June to November each year, the group collected bear droppings, and they have analyzed 2,079 samples. They found that the bears' diet changes with the seasons: In August, the bears feed on nuts from the Japanese stone pines that grow at high elevations, while in September, they consume salmonids. The research showed that the bears traverse different environments to benefit from mountain and marine resources.

Associate Professor Shimozuru points out that salmon catches have gradually decreased over the past decade, likely due to climate change, including warmer ocean temperatures from global warming. Last year, shortages of both salmon and stone pine nuts, coupled with a poor yield of acorns-another important autumn food source-resulted in more bears venturing into human settlements in search of food. As a result, more than 180 bears were killed for management purposes in Shiretoko alone.

Japanese stone pines, a mountain tree whose bounty sustains brown bears in the Rusha area (Photo by Yuri Shirane)

Toward better relations between bears and humans

While measures to prevent encounters with bears are necessary, Associate Professor Shimozuru believes it's also important to manage the bear population flexibly. "In Shiretoko, brown bears are recognized as a key element contributing to the area's World Heritage status, so simply reducing their numbers is not a solution," he explains. The gender and age of captured bears can significantly affect future reproduction and population size in the region, but age is not always easy to determine by appearance. Previously, age was estimated by anesthetizing the bear and extracting a tooth, but Associate Professor Shimozuru developed a highly accurate method for estimating bear age from blood samples, based on a technique previously used to estimate the age of other animals from DNA in the blood. In experiments with brown bears, this method allowed for age estimation with a margin of error of about one year. "Previously, we had to anesthetize bears and extract teeth, which put a significant burden on their bodies. Moving forward, I hope to explore whether we can estimate age from DNA obtained not only from blood but also from hair or droppings, and whether this method could be used for other bear species, such as Asian black bears."

Effective bear management requires scientific knowledge, including an understanding of the food environments that lead to increased bear sightings near human settlements, the bears' habitats, and the age and gender composition of the bear population. Associate Professor Shimozuru looks ahead, stating, "I want to continue using the knowledge we've gained to help foster better relations between bears and humans, with the goal of minimizing conflict while ensuring the survival of bears."

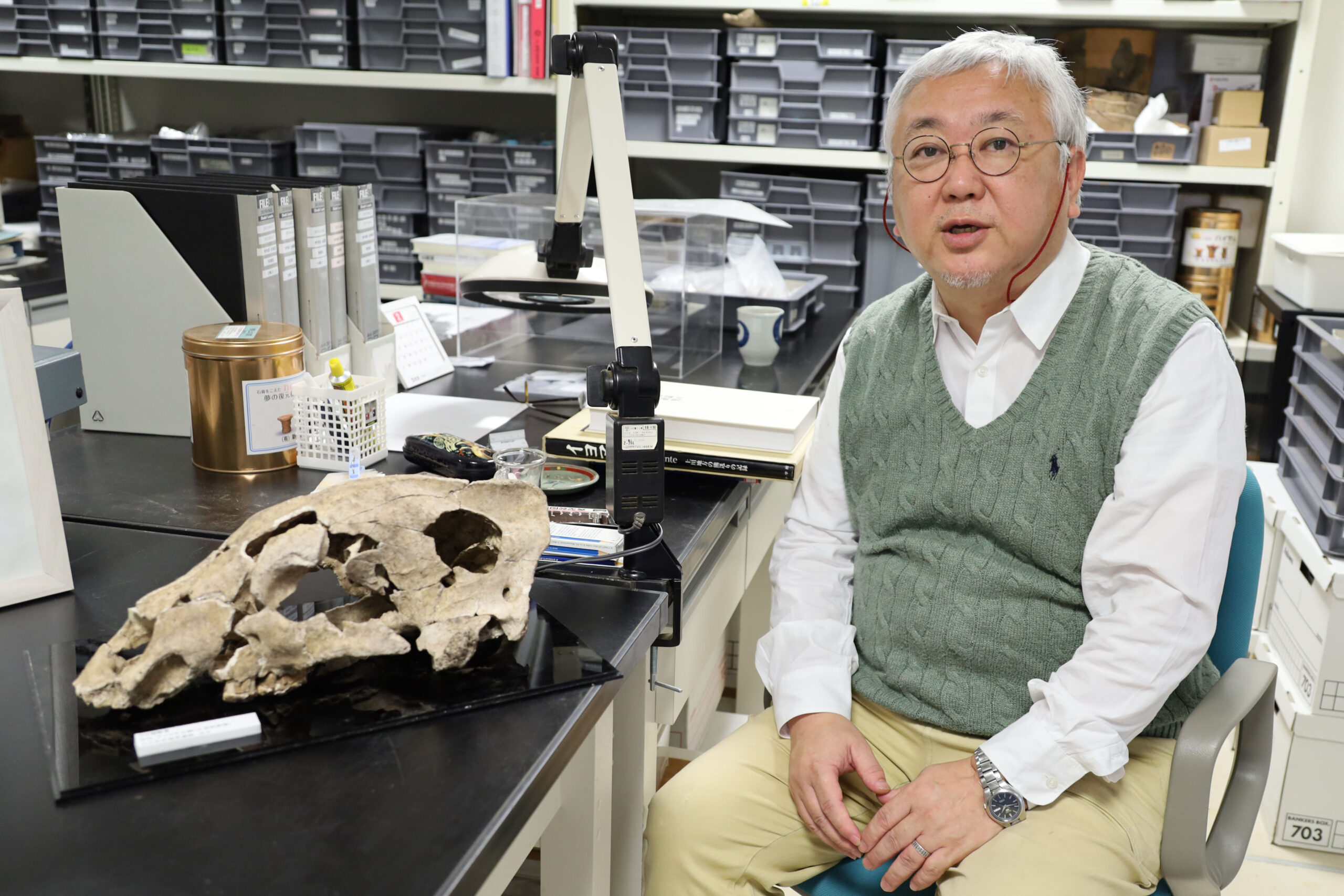

The iyomante (bear spirit-sending ceremony): The relationship between the Ainu people and brown bearsThe Ainu, the Indigenous peoples of Hokkaido, traditionally lived as hunter-gatherers and regarded animals that were deeply involved in their daily lives as "gifts bestowed by spirit-deities." Among these animals, brown bears held the highest status and were referred to in Ainu as kimunkamuy, meaning "spirit-deities residing in the mountains." After capturing a bear, the Ainu performed a ritual known as the iyomante to return the bear's spirit to the realm of the kamuy (spirit-deities). Professor Hirofumi Kato of the Center for Ainu and Indigenous Studies at Hokkaido University discovered evidence of the iyomante ritual in the form of a brown bear cranium with a large hole in the parietal bone during an excavation at the Ikushina-Kita Kaigan Site in Shari Town on the Shiretoko Peninsula. According to tradition, Ainu crafted a ceremonial decoration called an inaw (stick) by peeling the bark of willow or dogwood trees and shaving it into a thin, tuft-like shape using knives. This inaw stick, which served a purification function, was inserted into a hole made in the bear's cranium and was displayed on an altar until it naturally decayed. Professor Kato explains, "The Ainu have a cyclical philosophy: By respectfully sending the spirit of the bear, which is a gift from kamuy, back to the realm of kamuy through the ceremony, they ensure that the bounties of the mountains will return to them in the future." Regarding the relationship between humans and brown bears, Professor Kato comments, "For the Ainu, nature, including brown bears, is something to be treated with respect and dignity. They believe that humans live as part of an interconnected relationship with nature. In light of the bear-related issues that have arisen across Japan, I feel that now is the time to reconsider the relationship between humans and the natural world, including animals." |

This article was published in the Autumn 2024 issue of Litterae Populi. The full issue can be found here.