This article was published in the Autumn 2024 issue of Litterae Populi. The full issue can be found here.

Hokkaido University has a student group called the Brown Bear Research Group, also known as Kumaken. It studies the ecology of brown bears living in Hokkaido. They have single-mindedly followed the traces of brown bears for more than half a century. What have they uncovered through their steady efforts?

Former Kumaken leader Taiga Yamamoto (left) and current leader Moe Sakai diligently look for traces of brown bears

Tracking the traces of brown bears for more than half a century

"Poi-po-i, poi-po-i"-the chant of Kumaken members echoes through Hokkaido University's Teshio Experimental Forest in Horonobe Town, located about 300 km north of Sapporo, near the northern tip of Hokkaido. Clad in hiking gear, the students push their way through undergrowth as tall as they are while repeating their chant. This "poi-po-i" serves the same purpose as a bear bell, alerting bears to the presence of humans as the group enters the forest to conduct research. This chant has been passed down for generations within Kumaken. After chanting, the students continue their trek, listening carefully for signs of wildlife around them.

Founded in 1970, Kumaken conducts research on brown bears in Hokkaido, including in the suburbs of Sapporo. The Teshio Experimental Forest is a research site they visit annually. The students follow predetermined routes, searching for bear tracks, droppings, claw marks, and signs of feeding. At the same time, they count and examine the nuts, berries, and fruits that serve as food for the bears. Instead of making direct contact with the bears, they diligently study the traces left behind in the mountains to better understand their ecology.

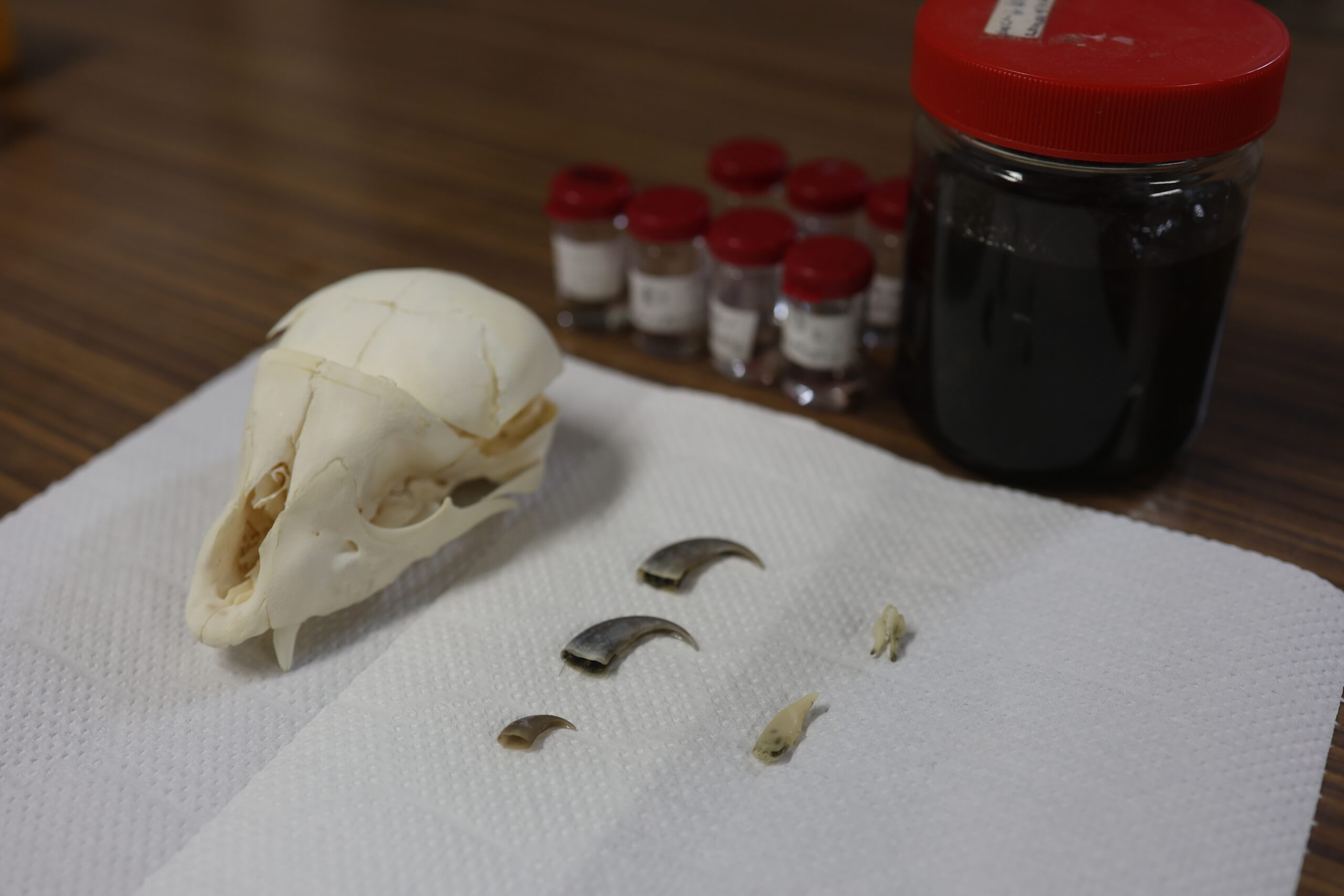

Being omnivores, bears produce droppings that vary in contents-such as digested berries, fruits, grass, and insects-giving each sample a distinct appearance. Taiga Yamamoto, a former leader of Kumaken and a third-year student at the School of Law, explains, "We collect all bear droppings as samples, rinse them, and preserve their contents in alcohol to analyze the bears' diet." Last summer's survey revealed that most of the bear droppings they collected contained very few seeds from berries and fruit. Last year saw poor yields of nuts, berries, and fruit in the mountains nationwide, and bears in Teshio also appear to have had difficulty finding enough food. The food shortage led to a significant increase in bear sightings near human settlements, which became a major social issue across Japan last year. Yamamoto notes, "During the transitional period between late summer and the autumn harvest, or in years of poor yields of berries and fruit, it seems that bear droppings containing dent corn used for livestock feed have increased." All these records on bear ecology have been carefully preserved since Kumaken's founding. Led by former Kumaken members, the group compiled 40 years of data, including on bear droppings and footprints, and published their findings in an academic paper in 2021.

Understanding and appropriately fearing bears

During its decades of research, Kumaken has never had a single bear-related incident. Before new members begin their first survey, they must review bear safety manuals and learn how to use bear spray. Before surveys, including those on bear dens, study sessions are held to pass down knowledge and safety measures from one generation to the next. Yamamoto emphasizes, "The most important thing is to avoid encountering bears. We make sure no one ever acts alone in the mountains; we only go after sunrise and avoid entering when visibility is poor, such as in fog." During the surveys, if they discover fresh bear signs-like footprints with small, distinct claw marks as well as mud splattered around; or large, cylindrical droppings-they immediately turn back.

Yamamoto has sighted brown bears several times during his research. The first time was in his freshman year when he was about to turn a corner on a mountain path and suddenly felt a senior student pull him back by his backpack. As they slowly backed away and looked carefully, they spotted a bear about 200 to 300 meters ahead. When they called out "poi-po-i," the bear noticed them and ran away, and they backed away slowly as well. "Honestly, it was terrifying," Yamamoto recalls. "Since then, I've been much more cautious to avoid encountering bears." Last year saw a rise in public interest in bears across Japan, with frequent sightings not only in Hokkaido and the Tohoku region, but also in Tokyo. Yamamoto paused for a moment before addressing how society at large can navigate its relationship with bears: "It's a difficult issue, and it's hard to generalize. Personally, however, I think we should understand bears and fear them appropriately. By doing so, I believe many incidents can be prevented."

Moe Sakai, this year's leader of Kumaken and a third-year student in the School of Science, said with a sparkle in her eyes, "What I love about Kumaken is that, no matter how simple a question may be, the group values the spirit of inquiry and gives us the freedom to engage fully in our research. I hope we continue to share our knowledge about bears and become even more dedicated to fieldwork while honoring our traditions."

A video introducing Teshio Experimental Forest, Kumaken's field base

This article was published in the Autumn 2024 issue of Litterae Populi. The full issue can be found here.