The first patient in a clinical trial to receive purified CAR-T cells manufactured at MUSC Hollings Cancer Center is home and is, so far, doing well, his doctor said.

Brian Hess, M.D., and Shikhar Mehrotra, Ph.D., have partnered for almost three years to get this clinical trial off the ground. They hope that the purified CAR-T cells will prove to have fewer side effects and a longer-lasting result than commercial CAR-T cells currently on the market.

Patient Ted Kopacko, who's lived with marginal zone lymphoma for 11 years, hopes that the treatment gets him off the merry-go-round of maintenance drugs that work for a while and then lose effectiveness.

"I had read about clinical trials and kind of already knew that I wanted to do something extra," he said. "And if there was an opportunity for me to get rid of this for a few years, then let's try it. I was for it. Otherwise, it's back to the same thing - doing treatments for the rest of your life."

CAR-T-cell therapy is an approved treatment for several types of lymphoma and multiple myeloma, once standard treatments have all been tried. In this treatment, a patient's T-cells - part of the immune system - are removed and then engineered in a lab to add a CAR, chimeric antigen receptor, which helps the T-cell to home in on specific proteins expressed on the surface of the cancer cells. The supercharged CAR-T-cells are then returned to the patient.

The treatment can be extremely effective against cancer - but it also can produce serious side effects, including cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity that can require hospitalization and close monitoring.

Hess, a hematologist-oncologist, has treated numerous patients with conventional CAR-T. He's seen some patients have great results, but he's not satisfied that the treatment is as good as it could be. Neither is Mehrotra, who specializes in targeting T-cell signaling.

Mehrotra is also scientific director of the Center for Cellular Therapy at MUSC. The center is key to this clinical trial; it's an FDA-registered cGMP (current Good Manufacturing Practice) clean-cell facility that offers scientists the ability to manufacture cellular therapy products - an ability that most hospitals do not have.

Manufacturing the CAR-T cells in-house potentially offers a number of advantages. It gives Hollings researchers control over the process so that they can create a purer product. It should substantially reduce the cost of this expensive therapy. And it means that the product is delivered to the patient's bedside fresh, rather than being shipped in a frozen state and then thawed, a process that could compromise the effectiveness of engineered cells, Mehrotra said.

Tweaking the CAR-T recipe

Creating CAR-T cells starts with designating the target on the cancer cells. For approved CAR-T-cell therapy, that's either the protein BCMA for multiple myeloma or the protein CD19 for lymphoma.

But Mehrotra is adding his unique spin. He's starting with a blueprint based on work by researchers at Loyola University Chicago. However, he's adding an additional cytokine "cocktail" that his group has patented for improved efficacy and persistence.

"When we put them back into the patient, they'll be able to sustain longer; that is, at least, what we have concluded from our previous preclinical studies in the lab," Mehrotra said.

The Loyola University Chicago recipe started with expressing a truncated version of the protein CD34. Like a team jersey, the CD34 will allow the researchers to pick out only those cells that have been modified into cancer-fighting machines. Most commercial CAR-T products contain not just the CAR-T cells but also a whole stew of cellular products, including T-cells that didn't take to the engineering process and dead cells. These extras may also contribute to cytokine release syndrome, a syndrome prompted by an over-response from the immune system.

Hess said they'll be able to ensure that 90% or more of the product contains the engineered CAR-T-cells.

"Compare that to the commercial product where the majority of the time they don't tell us what percentage of the product is CAR-T-cells versus other things," Hess said. "As an example, I had a patient who I was giving 150 million cells, and CAR-T cells were only 10% of that product. So, you're likely giving a lot of other T-cells with that, and those T-cells probably contribute to that cytokine release syndrome."

"We're really hoping that we prevent those higher grades of cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity," Hess added.

Seeking solutions

Kopacko, the first patient in the trial, said he wasn't overly worried about side effects. He's dealt with side effects over the past decade - he's just hoping for a better solution.

Like many young men, Kopacko, now 64, left a difficult home life by joining the military. He did his four years with the U.S. Marines and got out, establishing a career in international merchandise transport.

"It was interesting, but nothing glamorous. But it was solid. It's a solid industry," he said.

His four years in the Marines stayed with him, though.

"It taught me some things that stay with you forever. You can do whatever you want to do if you just put your mind to it and keep at it. It teaches you a little bit of toughness," he said.

Unfortunately, that time left a mark in another way. Kopacko was stationed at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, where the water was contaminated by industrial solvents. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs now automatically considers several cancers and Parkinson's disease to be linked to time spent there, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Kopacko's marginal zone lymphoma is a type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

"A lot of people were there. A lot of families were there. That's what hits me the most - not the service members but families, the children who lived there and came down with all these horrible things," Kopacko said. "And so many people have it worse than me, have worse kinds of cancer. My first doctor had told me, 'If you're going to get one, this is the one to get.'"

Kopacko was first diagnosed in 2013 after going to the doctor to check on his extreme fatigue and weight loss. Thus began the journey of trying to find the right therapies.

"Some of the combinations would last for six months. Some would last for a year. But, eventually, it kept coming back, and we would try something different," he said.

"When it came back again at the end of 2020, that's when I said, 'Enough, let's retire and put all my time toward getting better.'"

For the past couple of years, he was on a maintenance drug that was working well.

"The past year is when I think it started to lose its grip, and then once it started to lose its grip, that's when the VA put me over here," he said.

When Hess first met Kopacko, he wasn't in great shape. He needed bridging therapies to get the disease under control enough that he could undergo CAR-T-cell therapy.

Marginal zone lymphoma does not have an FDA-approved CAR-T-cell therapy. However, this clinical trial is open to people with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes that have yet to be approved for CAR-T-cell therapy, including marginal zone lymphoma, Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, Burkitt lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma. Also included in the trial are subtypes that do have FDA approval for CAR-T-cell therapy, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma.

"He's a great patient for it because his marginal zone lymphoma does not have a current approval for CAR-T, and he's been through so many different therapies," Hess said. "There's nothing left under standard of care that would be a good option for him."

Launching the clinical trial

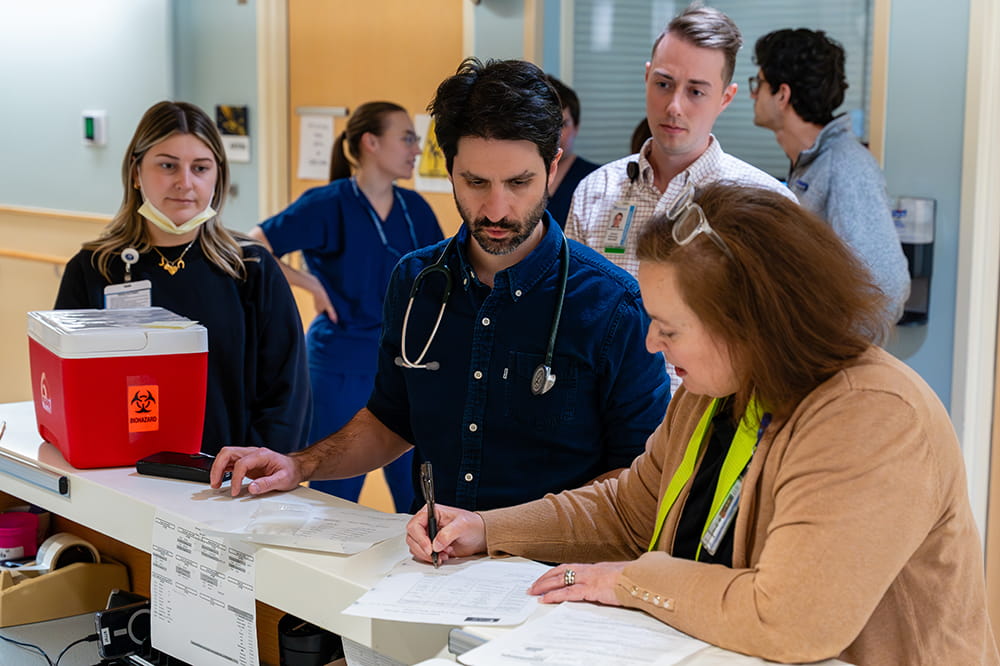

All of the months of planning, testing and protocol development led up to Jan. 8, when Kopacko became the first patient in the trial.

Excited to see the project come to fruition, the entire Center for Cellular Therapy team escorted the small cooler containing the CAR-T-cells across campus from the center's home in the Clinical Research Building to Ashley River Tower. This MUSC Health hospital houses the specialized HOPE (hematologic oncologic protective environment) unit.

Inside the cooler was an even smaller IV bag containing millions of Kopacko's own cells, engineered into CAR-T-cells.

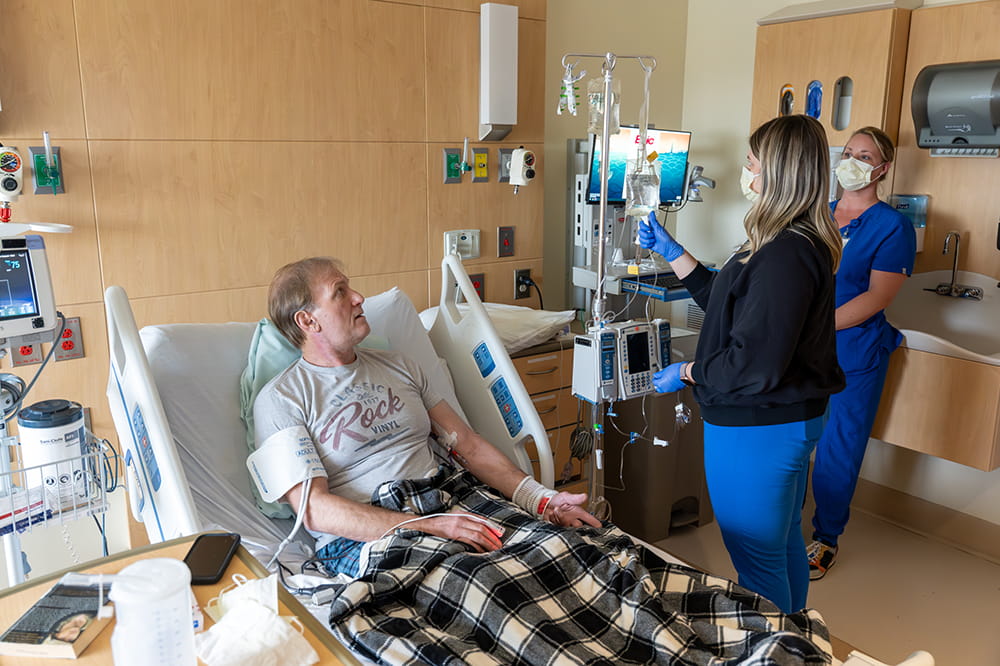

After the official handoff from Mehrotra's team to Hess, the nursing staff took over, carefully setting up the infusion to reintroduce the cells to Kopacko's bloodstream.

The worst of the cytokine release symptoms typically occur within the first two weeks of infusion. The clinical team kept Kopacko in the hospital for a week, but he didn't experience cytokine release syndrome (CRS) or neurotoxicity.

"Currently the patient is greater than two weeks out from receiving CAR-T and has not experienced any CRS or neurotoxicity," Hess said. "I was excited to see him tolerate it so well and hope this to be the outcome for patients to come."

The longer-term question is whether the treatment is more durable than existing CAR-T-cell therapy, meaning that the CAR-T-cells can continue doing their job longer.

More durable therapy will give Kopacko more time with his family, including his 6-year-old and 4-year-old grandkids, who live only a few miles away.

"I get to see my grandkids all the time," he said. "There's nothing better at this point of your life than to be able to watch your grandkids grow up."

To get a handle on results, the research team will need results from multiple patients. The second patient in the trial is scheduled for the beginning of the month. In the meantime, Kopacko maintains a hopeful spirit.

I want nothing but good people and good things in my life," he said. "I don't have time for people with bad attitudes."