It has long been known that some plants tolerate drought better than others. As some of the first to do so in the past 100 years, Danish scientists have investigated the mechanisms behind the Aloe plant's ability to survive extended periods of drought. New knowledge could contribute to more resilient crops for a future of more weather extremes.

Researchers from the Natural History Museum of Denmark and the Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences at the University of Copenhagen, have in collaboration with researchers at the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew in England, demonstrated that certain Aloe species shrink, or more scientifically speaking - fold - their cell walls together. In doing so, the plants preserve resources during drought. Concurrently, the carbohydrate (polysaccharide) composition of their cell walls are altered. The results have just been published in the journal Plant, Cell and Environment.

"Our results tie changes in carbohydrate composition with the Aloe plant's ability to manage extended periods of drought. It is highly relevant, that we understand the physiological mechanisms that allow certain plants to survive under extreme conditions, due to climate change and the potential for severe climatic fluctuations," says plant biologist Louise Isager Ahl of the Natural History Museum of Denmark.

Useful genetic traits

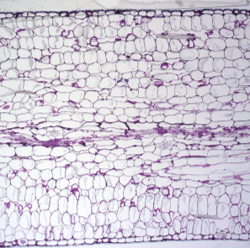

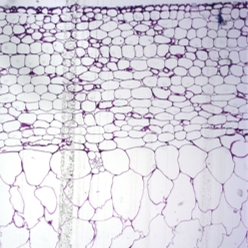

The majority of succulents can survive in areas susceptible to shorter or extended periods of drought. This ability has made succulents popular as houseplants. Aloe vera, along with other Aloe species, have a special tissue in the middle of their leaves known as the hydrenchyma. This tissue has a well-developed ability to control water content in leaves.

One of the mechanisms that succulents use to resist drought is to fold their cell walls together during dehydration and unfold them again as water becomes available. The unique composition of carbohydrates in the cell walls and within the cells of the hydrenchyma is partly responsible for these plants' ability to regulate and retain water. It is a trait that may be transferable to other plants.

"I can imagine that by identifying and understanding the genetic mechanisms allowing Aloe species to fold and unfold their cell walls, we will be able to integrate similar mechanisms into crops to make them more resilient to climate change," says Louise Isager Ahl.

Results based on 100-year-old observations

The first descriptions of succulent plant species with folded cell walls were made by a German botanist at the end of the 19th century. His observations were investigated further by another German botanist at the beginning of the 20th century. Since then, few researchers have delved into the underlying mechanisms behind cell wall folding. Not until Louise Isager Ahl and Jozef Mravec wondered if there might be a correlation between the changes they observed in carbohydrate composition and the folding of cell walls. Together, they began studying the composition of carbohydrates in Aloe plants, both before and after droughts.

"The ability to survive drought by cell wall adaptations is also found in other succulents, but the changes in carbohydrate composition in Aloe, in relation to drought, had not previously been investigated in Aloes. The unique collaboration between botanists and carbohydrate chemists in this project has provided us with a better understanding of the composition and function of these carbohydrates in relation to the drought management abilities of these plants," says Louise Isager Ahl.

- Read the journal article in Plant, Cell and Environment: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/pce.13560

The research group is consists of: Louise Isager Ahl, Postdoc & PhD, Natural History Museum of Denmark; Nina Rønsted Professor, PhD, Natural History Museum of Denmark, Jozef Mravec, Assistant Professor & PhD, Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences; Bodil Jørgensen, Associate Professor & PhD, Department of Plant and Environmental sciences, Olwen M. Grace, Senior research leader & PhD, Comparative Plant & Fungal Biology, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Dr. Paula J. Rudall, merit researcher (emeritus), Comparative Plant and Fungal Biology, Royal Botanic Gardens Kew.