Rising rents and housing shortages aren't just making it harder for young Canadians to find a place of their own-they're fundamentally changing how families live together, according to new research from the University of British Columbia.

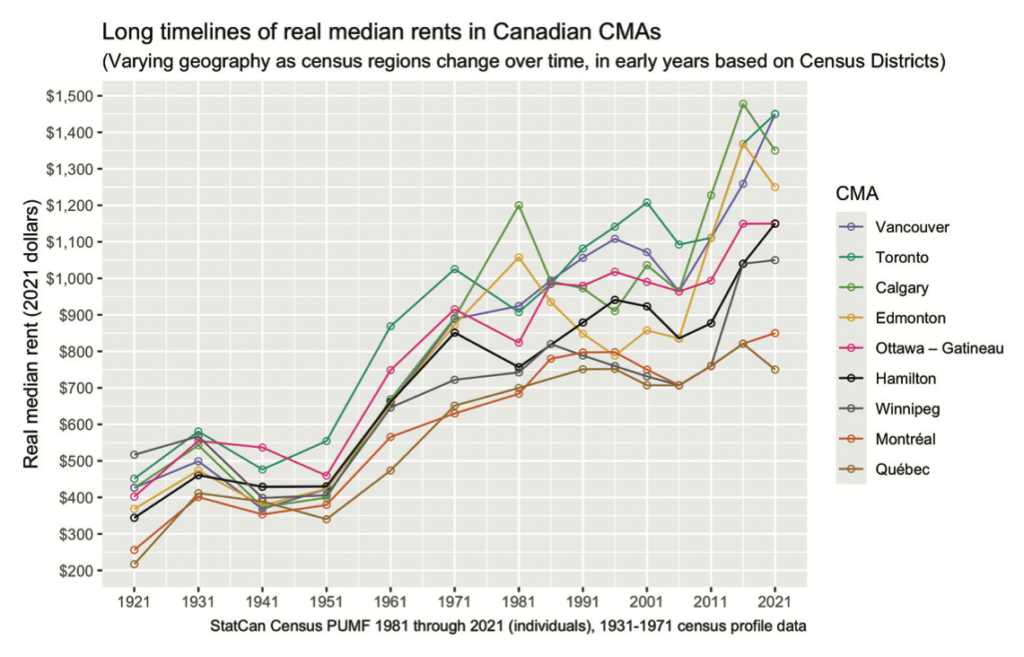

The study, published in The History of the Family , examines how rising housing costs across major Canadian cities have affected household formation from 1981 to 2021. The findings show that in cities like Toronto or Vancouver, where rents have surged, the number of young adults forming their own households has plummeted. Instead, many are staying with family or moving in with roommates to manage costs.

In sharp contrast, cities where rents have remained lower, like Quebec City and Montreal, have seen more stable or even increased household formation.

"The historical trend in Canada has been that people want to form independent households. But when housing is scarce and expensive, they adapt by living in ways they wouldn't otherwise choose," said lead author Dr. Nathanael Lauster, an associate professor of sociology at UBC.

The high cost of independence

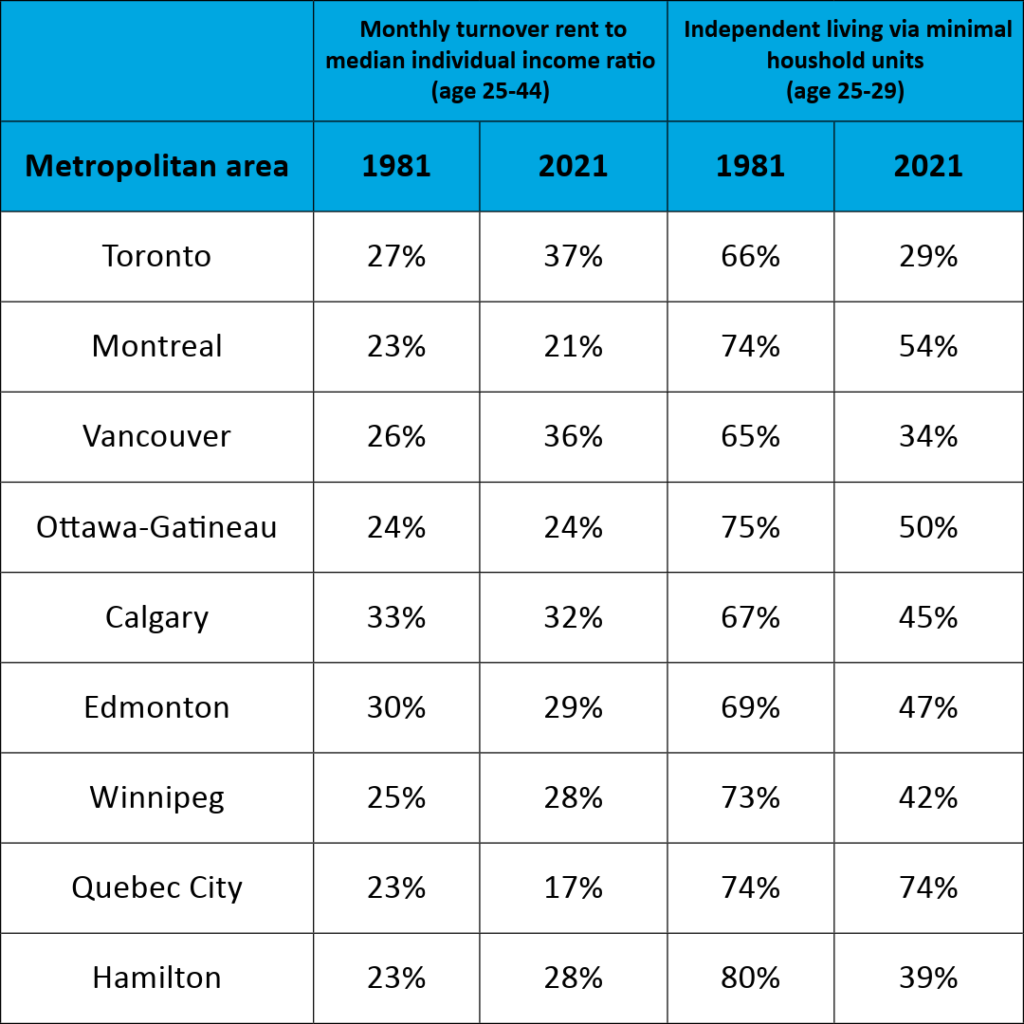

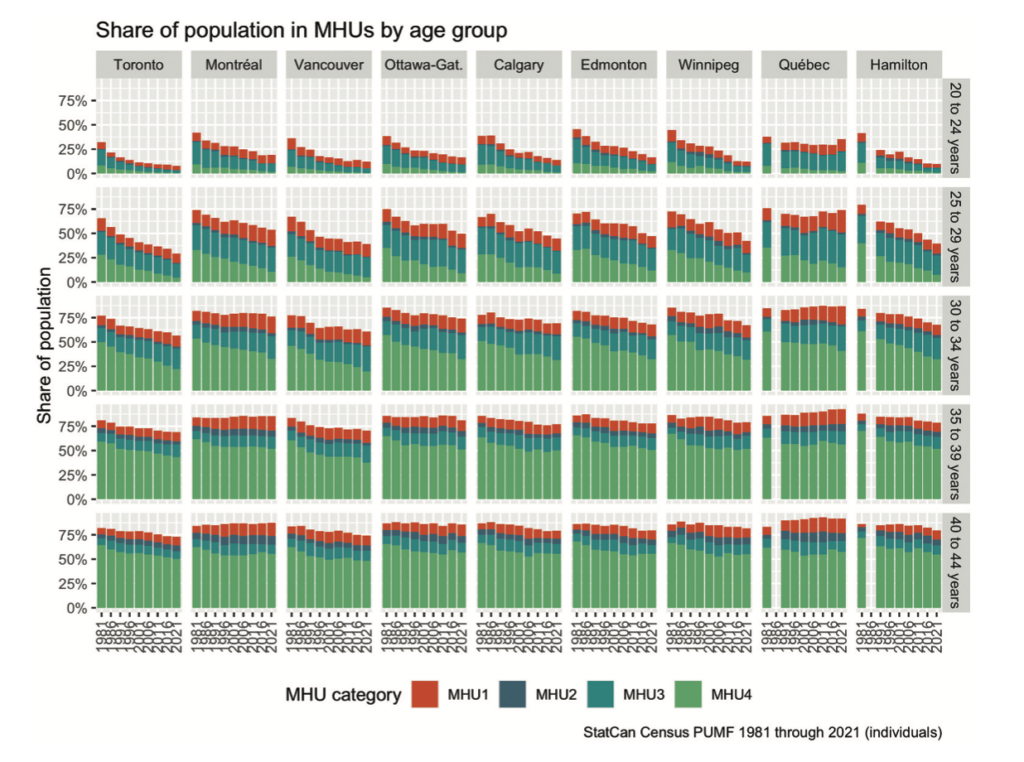

The study analyzed census data from nine major metropolitan areas: Toronto, Vancouver, Montreal, Calgary, Edmonton, Ottawa, Hamilton, Winnipeg and Quebec City between 1981 and 2021. It focused on minimal household units (MHU), which include single-person households, couples, couples with children and single parents with children.

The researchers compared these trends to housing accessibility, as measured by inflation-adjusted turnover rents. They found a strong link between rental costs and household formation. In cities where rents have soared, millions of Canadians are "stuck in place," unable to move into their own households.

Key findings include:

- Across all metropolitan areas, the number of smaller households increases when rent is lower and decreases when rent is higher.

- Rising rents have been accompanied by more young adults "doubling up" instead of forming their own households. While these effects are visible across age groups, the declines are most readily apparent and interpretable for the 25- to 29-year-old range.

- The burden of rent has increased. In 1981, median rent in Toronto and Vancouver consumed 25-27 per cent of the median young adult income. By 2021, this had risen to 36-37 per cent, forcing more people to share housing costs.

- In Quebec City and Montreal, the proportion of young adults living independently remained much higher, rising to 75 per cent in Quebec City and 50 per cent in Montreal. During this time, rents fell as a proportion of income, from just under 25 per cent to around 21 per cent in Montreal and 17 per cent in Quebec City.

- In 1981, over two-thirds of 25- to 29-year-olds in Toronto and Vancouver lived independently in MHUs. By 2021, this had dropped to just over a quarter in Toronto and one-third in Vancouver.

- For every $1,000 increase in median rent, the share of young adults forming their own households declines by 23 per cent.

- The largest drop in independent living was among couples with children, reflecting trends in delayed childbearing. In Quebec, this was offset by increases in single-person or coupled households.

- Newcomers to an area were more likely to form their own households, likely due to more limited family and social connections.

The study also controlled for income levels and demographic shifts, and explored how different cultural backgrounds might shape preferences for living arrangement. It found that while cultural differences matter, the biggest predictor of household formation is the cost of rent relative to income.

Housing policy isn't just about numbers - it's about choices

Government housing policies typically estimate housing needs based on in-migration and population growth, but this approach overlooks affordability's impact on household formation.

"Our research shows that households are malleable," said co-author and data scientist Dr. Jens von Bergmann, of MountainMath Software and Analytics. "It confirms what many renters already know-high rents don't just squeeze budgets; they fundamentally change how people live."

The researchers argue that increasing the housing supply would allow people not just to move out, but to form households in entirely different ways. Policymakers must account for the households people want to have, not just those they're forced into by high costs.

While rent freezes or subsidies may seem like potential solutions, researchers suggest that addressing the root issue is key.

"Housing operates as a system. If the goal is to give Canadians more freedom to live independently, the most effective solution is to increase the housing supply, particularly in high-cost cities," said Dr. Lauster. "Otherwise, we're just shifting the problem around."