NASA space debris expert Dr Don Kessler was the first to observe that once the amount of space debris reaches a critical point, unavoidable collisions will cause more debris, in a disastrous chain reaction that will make space inaccessible to us. This has been termed the Kessler Syndrome. Once the cascading collisions begin, they cannot be stopped.

For the past two decades, some low-Earth orbits may already have accumulated that critical amount of debris - or so Kessler has calculated. We are like the skier beneath the avalanche-prone ridge, with dangerous amounts of snow built up and awaiting the smallest shift to trigger catastrophe.

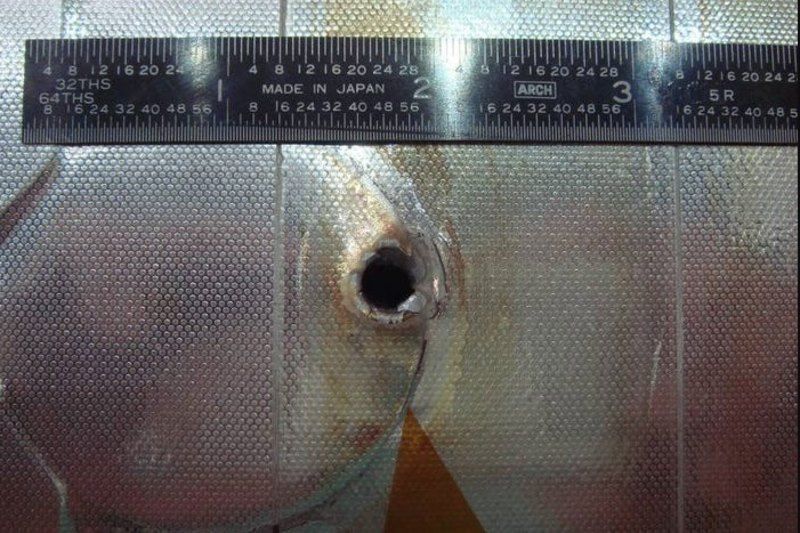

Already, space experts estimate there are 12,000 pieces of debris 10 centimetres long and larger that we can track, but nearly one million from one to 10cm in size, and over 100 million pieces smaller than a centimetre that we simply can't see coming. At the speed with which such pieces of debris travel in orbit, a single screw has the energy of a grenade upon collision.

Since we rely on satellite technology for everything from navigation to weather reports to communication to security networks underpinning your local ATM, if space were to become inaccessible it would dramatically change our way of life.

Cleaning up orbit

Many scientists are working on identifying and removing space debris from orbit. Some use old-fashioned techniques inspired by the age of sail, such as harpoons and nets, to remove larger pieces of debris. But smaller pieces can hardly be seen, let alone captured.

Earth's atmosphere is always shimmering, like the road ahead on a hot day. It makes it hard for astronomers to see objects in space, particularly the smallest of space debris.

NASA image showing damage to the Endeavour space shuttle's radiator from space debris. circa 2007. CREDIT: NASA

That's where Electro Optic Systems (EOS) technology comes in. From Mount Stromlo in Canberra, Australian astronomers affix a laser to their telescope and shoot it into the sky, whose shimmering action then distorts the laser light. As astronomers know the laser should be a point of light, they can deform the telescope's mirror until the laser image sharpens back to that pinpoint. The effects of the atmosphere have been corrected and now they have a telescope that can see the objects behind that laser point.

With this sharpened view astronomers can spot debris and advise countries and companies to move their spacecraft, satellites or astronauts away from danger. They are also planning to use a different high-powered laser to shoot small pieces of debris - the pressure from the laser slowing the debris so it lowers its orbit towards the Earth, hitting the upper atmosphere and eventually burning up on re-entry.

Australia has an important role in this global issue, as we monitor vast skies with space technologies that few others in the Southern Hemisphere have.

Avoiding Kessler Syndrome

It is vital we avoid causing more space junk. Since the 1950s we have sent thousands of rockets, satellites and assorted objects into space. That number is growing exponentially. Just this year, SpaceX set a record for the number of satellites sent to space on a single rocket: 143.

Given our reliance on space and the incredible potential of satellite technology, we cannot expect countries and companies to stop sending satellites into orbit, nor should we want to. But as space becomes more populated, we will no longer be able to rely on human reaction to move satellites and the International Space Station out of the way in time. More collisions will cause more debris and eventually the avalanche will be set in motion.

But what if satellites could move themselves out of the way?

Artificial intelligence (AI) can be used to create a system of satellites smarter than their predecessors, able to avoid debris and remain whole and operational.

However, if these AI-enabled satellites cannot work together, the worst-case scenario could see them catalyse the very disaster we are trying to avoid. A satellite avoiding a single screw could shift out of the way, causing another satellite to move and another until a domino effect causes crashes - perhaps into the International Space Station, our slowest-moving asset and home to our astronauts.

Swinburne University of Technology has partnered with professional services network EY (formerly Ernst & Young) and their space technology and AI lead for Oceania, Dr Olivia Sackett, the CSIRO's data science research and engineering arm, Data 61, and the Australian space industry consortium SmartSat CRC to develop an industry standard for AI in space, so that systems from different owners can operate in the same space, literally.

The project, called 'Responsible AI in Space', is a collaboration between space scientists, law and policy experts, the space industry, government and practitioners in the emerging field of AI assurance.

AI assurance is about maximising the benefits and minimising the harms associated with AI-enabled systems. The team will create a framework that companies, satellite operators, regulators and insurers can use to assess the trustworthiness of AI-enabled systems in space.

Responsible AI is the new final frontier in space - and it may be our final hope to preserve it too.

This article is republished from The Age under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.