According to the United Nations Environmental Program, nations across the globe produce about 300 metric million tons of plastic waste every year. That's nearly equivalent to the weight of the entire human population.

Where to put all of those plastics or how to recycle them are just two of the problems we face. Another one is the increasing prevalence of microplastics and even smaller nanoplastics in our environment. They are the tiny particles smaller than a single bacterium that break off during plastic degradation, making them very hard to clean up.

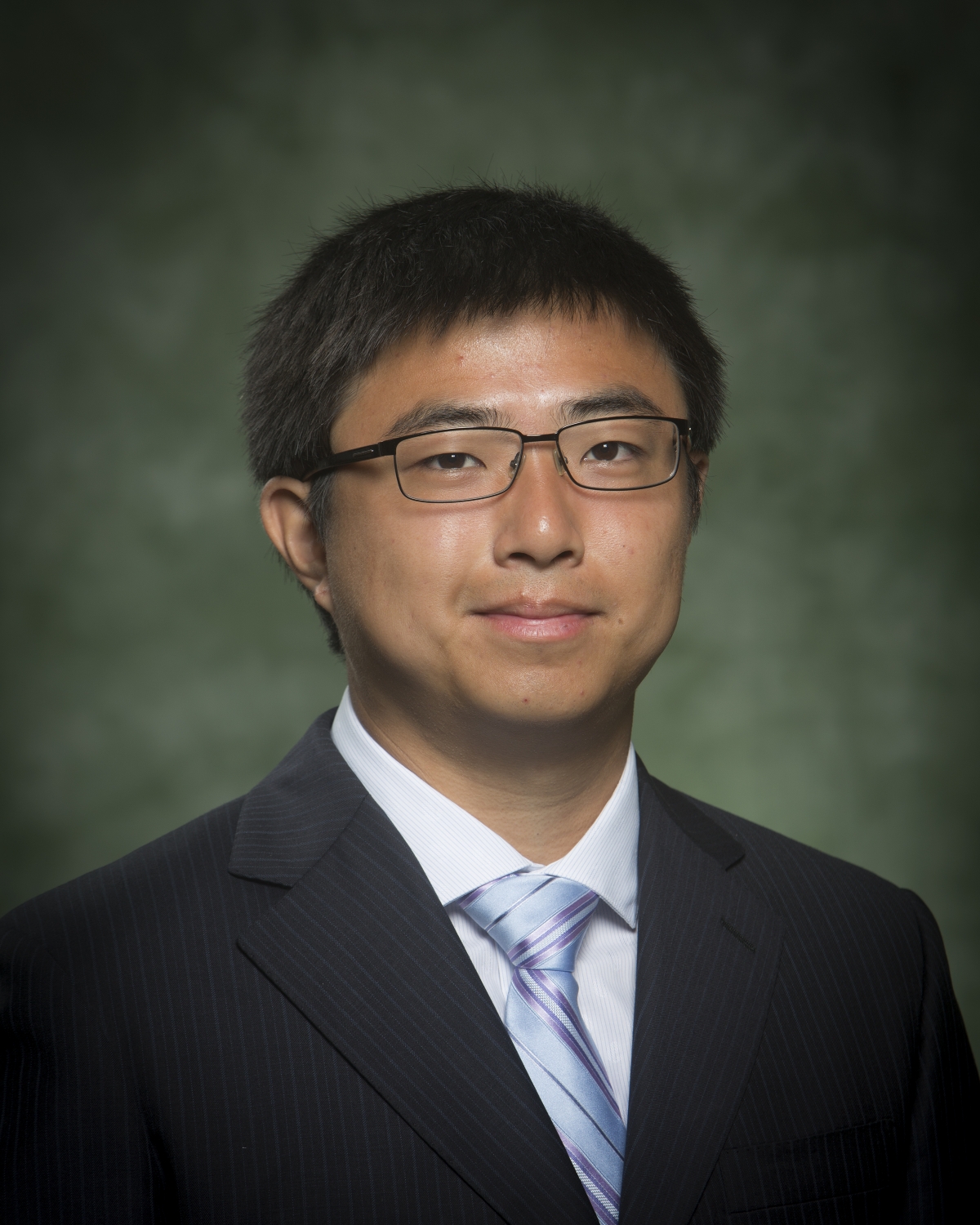

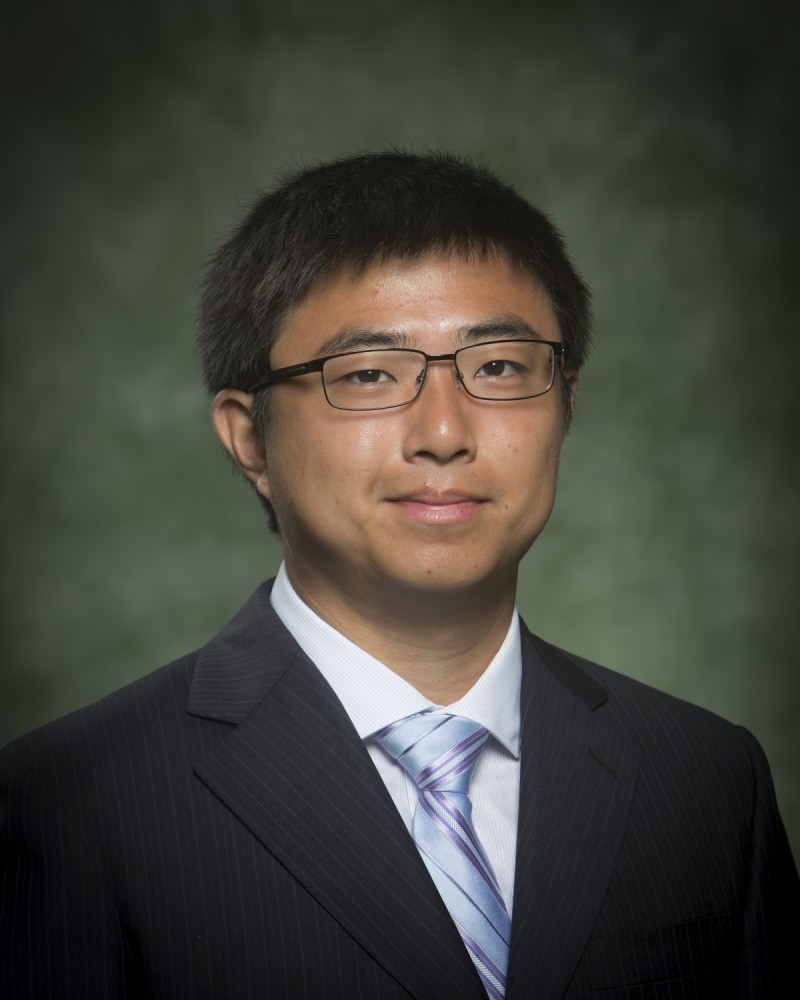

Humans and animals unintentionally could ingest nanoplastics in much of the food and drinks they consume. Researchers are investigating how that affects our health - and among them is Associate Professor Xin Yong, a Department of Mechanical Engineering faculty member at Binghamton University's Thomas J. Watson College of Engineering and Applied Science.

Recently, Yong and Assistant Professor Ke Du from the Rochester Institute of Technology received funding from the National Science Foundation's Chemical, Bioengineering, Environmental and Transport Systems (CBET) Division to examine the effects of nanoplastics on living cells. Binghamton's portion of the grant is $266,014.

Yong and Du's research differs from other studies because it will replicate the complex shapes that plastic particles can have as they degrade.

"Most of the previous studies focused on using nanometer-sized plastic spheres that are made in a laboratory to represent those particles," Yong said. "They have the same chemical composition and surface properties as what we see outside the lab. However, the most important thing is the shape, and in the real world, the shape is not going to be regular. During natural degradation, particles can never become a very perfect sphere."

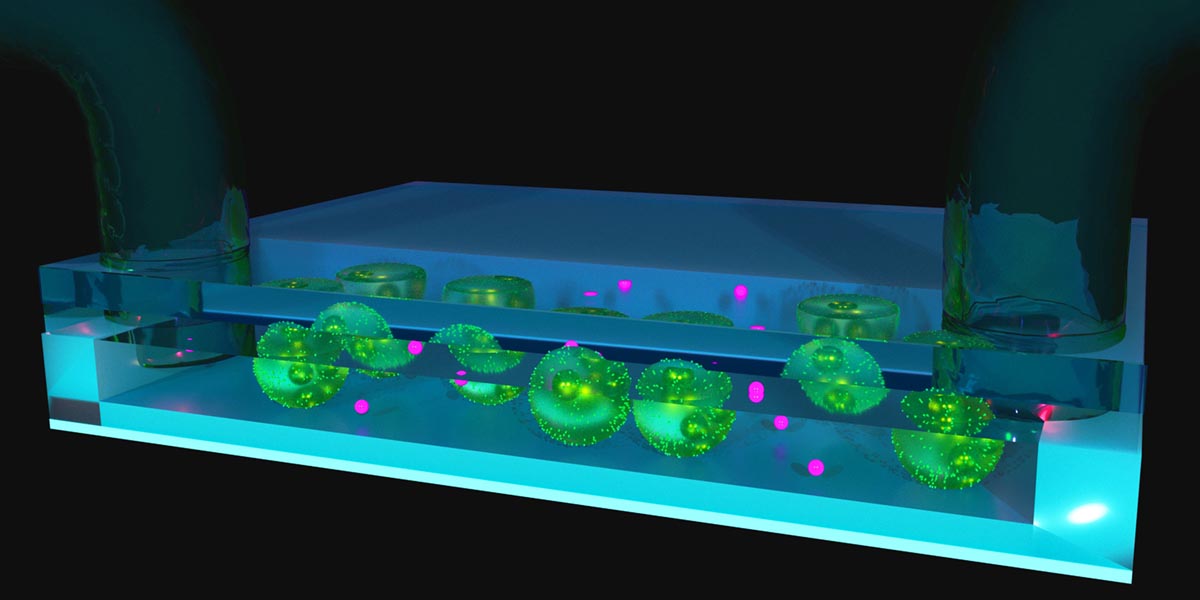

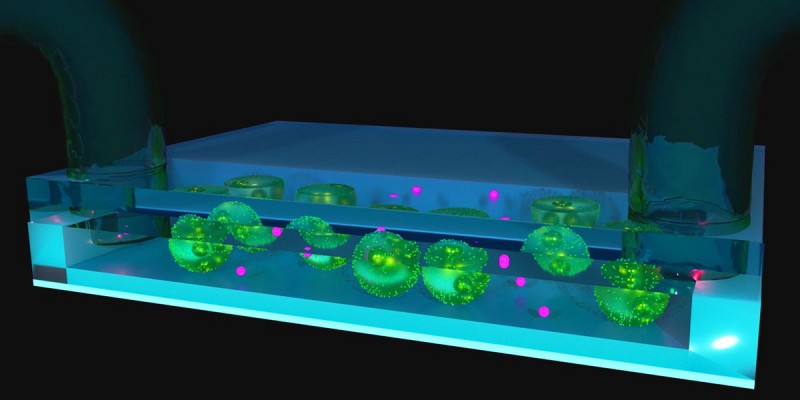

Because it is challenging to do the experiment with nanoparticles collected from the environment, such as a nearby stream, the team needs to create them a different way. Their proposal is to manufacture silver particles in a variety of irregular shapes and coat them with the same plastics that are breaking down after disposal. There also is a florescent component that will help to track the nanoplastics inside living cells.

"Because of their irregular shape, discarded nanoplastics have edges and sharp tips," he said. "They could easily damage cell walls as well as the membranes, which could kill the cell."

Du's part of the project at RIT is to make the irregular particles, introduce them to microalgae and observe how the tiny organisms interact with the nanoplastics.

Of particular interest is how the cells wrap around and absorb nanoplastics through a process called endocytosis. Yong will develop computer models simulating how this might affect the cells, and he will compare those simulations with actual results.

"We start with algae because we recognize it's a very important component of the food chain," he said. "Plankton will eat algae, and then plankton will be eaten by small fish. It goes all the way through the food chain, so this is a starting place to understand the uptake of these nanoplastics."

The two researchers have collaborated in the past, but this grant is special, Yong said: "This is the first proposal we wrote together, and we're really fortunate and appreciative that the NSF is supporting this research."

One component of the grant will involve outreach to the community, particularly high school students, to increase their awareness about the potential dangers of microplastics and nanoplastics. By tapping into a hobby that has gained a wider following in recent years, they will stress to young people about how to dispose of plastics in a more environmentally friendly way.

"The plan is to create videos that introduce the issues around nanoplastics and use 3D printing as something that students can relate to, because that has become more common outside of laboratories in the past 10 years," Yong said. "You can buy a plastic 3D printer for a few hundred dollars and do a lot of things at home. We can start the discussion about recycling the things you make and then move on to the wider global problem."

Yong and Du's NSF research is "Understanding 'wild-type' nanoplastic uptake in single microalgae cells with fluorescence tracking and computational modeling" (award #2034855).