Hydrogen is conventionally extracted from natural gas. In a reaction with oxygen, it generates energy which we can use for a variety of purposes, including to power machinery and vehicles. The chemical reaction creates no pollution — just water.

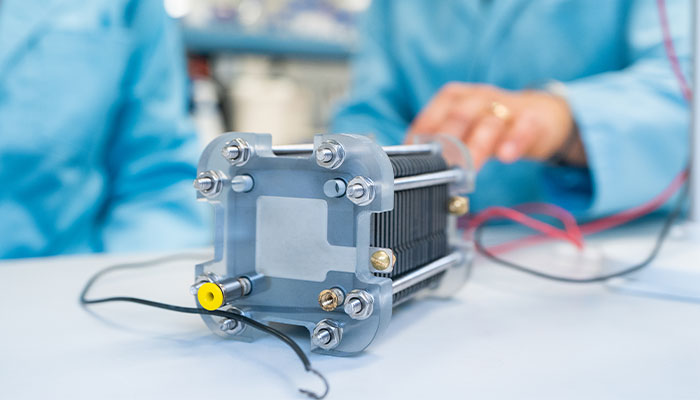

Hydrogen fuel cells (HFCs) convert the hydrogen into electricity to power passenger vehicles, trucks and buses. Larger HFCs can deliver back-up power to a whole building, replacing diesel generators.

The problem is that 99 per cent of all hydrogen fuel used in the world right now comes from coal and natural gas which are fossil fuels.

To get the hydrogen, you blast natural gas with steam at more than 700 degrees Celsius in a process known as steam methane reforming. This is energy-intensive and creates a lot of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change.

While the hydrogen fuel combustion itself produces no carbon emissions, the process to make hydrogen does.

Hydrogen produced from coal or gas in this way is called 'black and grey hydrogen' respectively, while 'blue hydrogen' refers to a process in which the carbon dioxide is captured from coal gasification and stored beneath the earth.

So, while the hydrogen fuel combustion itself produces no carbon emissions, the process to make hydrogen does.

Renewable sources

The good news is that the remaining 1 per cent of global hydrogen supply is generated using renewable energy, and that's where there's a lot of research activity. You could almost say that it's a race to develop the most efficient and least expensive renewably generated hydrogen.

Key alternative: A hydrogen fuel cell, which can convert hydrogen into electricity to power vehicles, while larger HFCs can deliver back-up power to a whole building.

One of these 'green hydrogen' methods involves running an electric current generated by wind turbines or solar panels through water using an instrument called an electrolyser to split the hydrogen from water.

Similarly, nuclear power is also being considered to create 'pink hydrogen'.

Biological waste is another possible source – and this is where a group of researchers at Macquarie are involved.

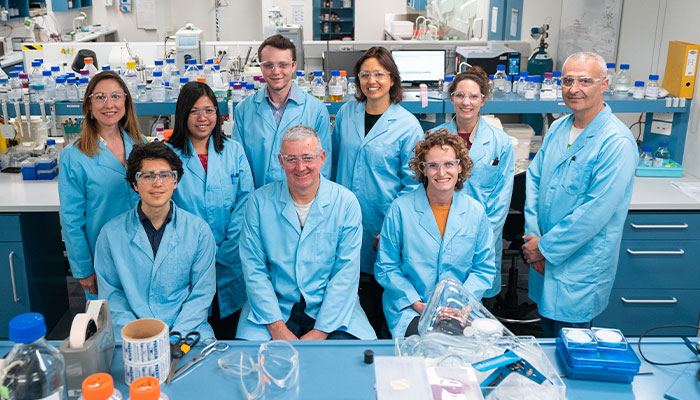

Three Macquarie academics, Professor Robert Willows, Associate Professor Louise Brown, Dr Kerstin Petroll and I have formed HydGene Renewables, a company developing processes to extract hydrogen from farm waste such as stubble — the stalks left behind after harvest from wheat or barley.

The challenge now is to bring the price of extraction down so that it's comparable to fossil fuels.

Through our process, we extract sugar from the stubble which we then feed into our engineered bacteria, which produces hydrogen.

The plan is that farmers use farm waste on their property to create their own hydrogen day or night, with no dependence on wind or sun, to power their vehicles and farm machinery so they'd have their own closed-loop, on-farm source of energy from a renewable source.

We anticipate our technology will be ready to go to market by 2025. The challenge now is to bring the price of extraction down so that it's comparable to fossil fuels.

Hydrogen power uptake

Hydrogen fuel produced from 100 per cent renewable electricity is already being used in Australia. There's a trial fleet of 20 hydrogen-powered government vehicles in Canberra and a hydrogen filling station.

Turning farm waste into fuel: The research team at HydGene Renewables (front, from left) Ari Edmonds, Robert Willows, Louise Brown and (back, from left) Jocelyn Johns, Thi Huynh, Samuel King, Natalie Curach, Kerstin Petroll and Tony Jerkovic.

Hydrogen storage tanks are also lighter than electric batteries and the car can travel further on one tank compared with electric vehicles.

Filling a vehicle with hydrogen is also as fast as filling it up with diesel or petrol — you don't have to wait while an electric battery charges. Manufacturers, such as Toyota and Hyundai, have already created electric- and hydrogen-powered cars.

Speed advantage: Filling a vehicle with hydrogen is as fast as filling it up with petrol – you don't have to wait while an electric battery charges.

What the world needs now is more funding for researchers, such as our team at Macquarie

That would help speed up deployment of the technology we need, lower costs and improve efficiency – and bring about more rapid adoption at scale of a key alternative to fossil fuels.

Dr Tony Jerkovic is a post-doctoral researcher in the Department of Molecular Sciences at Macquarie University.