Many disease-causing bacteria are able to inhibit the defense mechanisms in plants and thus escape dissolution by the plant cell, a process known as xenophagy. Animal and human cells have a similar mechanism whereby the cell's defenses 'eat' invading bacteria - yet some bacteria can inhibit the process. An international research team has now described the inhibition of xenophagy in plants for the first time. The team is headed by Professor Suayb Üstün from the Center for Plant Molecular Biology at the University of Tübingen and the Ruhr-Universität Bochum. The study has been published in The EMBO Journal.

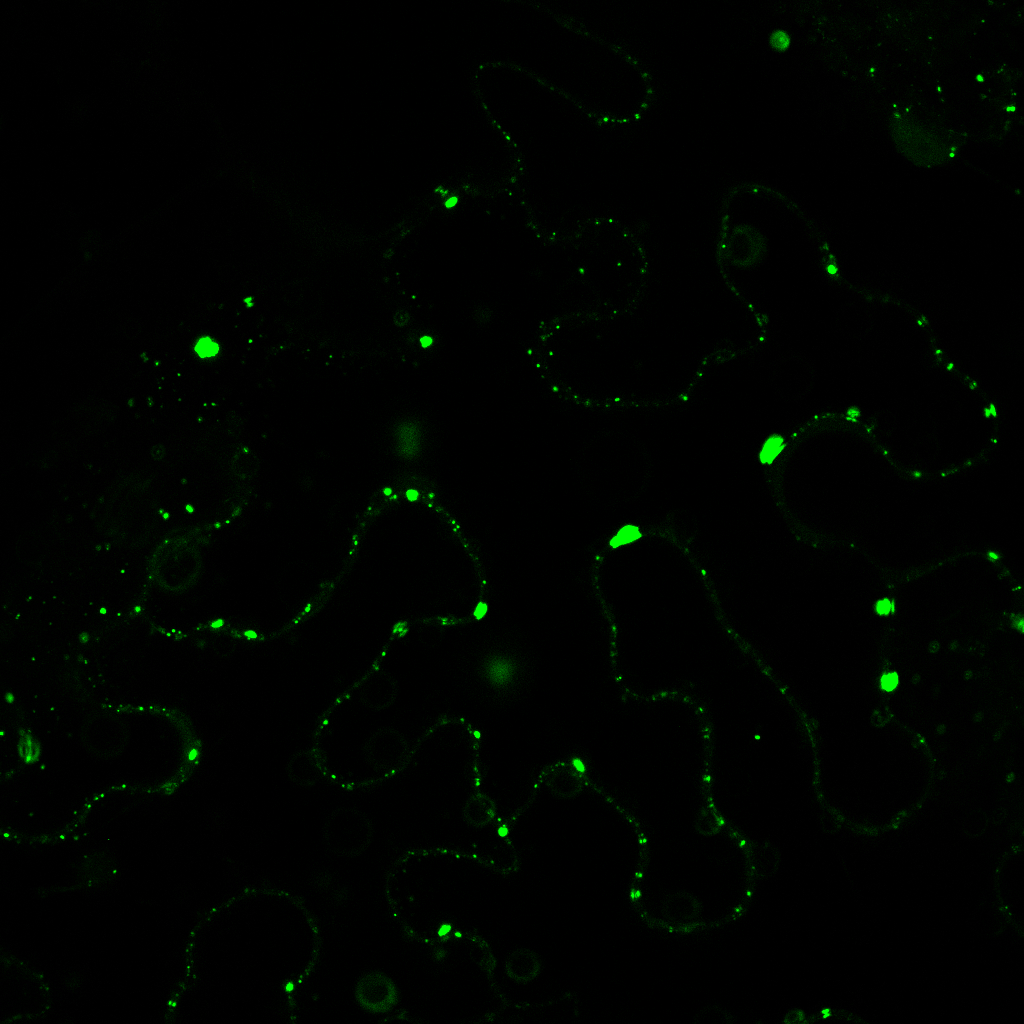

Cells must constantly adapt the proteins inside them to changing functions and to influences from their surroundings. "Constant protein degradation is unavoidable, otherwise the cell becomes cramped and runs out of material," explains Suayb Üstün, whose working group studies these strictly regulated degradation processes. When the cell has to degrade large protein complexes, insoluble aggregates or entire organelles, it usually uses a process known as autophagy, literally 'eating itself.' "Animal and human cells also sometimes use this method of degradation when they want to eliminate invaders such as pathogenic bacteria. In this case, the process is also called xenophagy - eating the stranger," says the scientist.

Arms race between host and pathogens

But the arms race between host and pathogen does not end there. Some bacteria have developed proteins that block the autophagy machinery directed at them. This gives them an advantage and they can spread further. "This state of research has been known for several years in human cells. With plants, we haven't got that far yet. There is an important difference between autophagy in plant and animal cells - in plants, pathogenic bacteria do not penetrate the cells. They stay in the extracellular space," says Üstün. This is the case, for example, with the bacterium Xanthomonas, which causes wilting and rotting of leaves, stems and fruits in a whole range of plants and also affects tobacco, the model plant studied by the research team.

"Xanthomonas bacteria introduce an effector into the plant cells. We found that this suppresses an important component of the autophagy machinery. This allows Xanthomonas to spread further," Üstün explains. "However, the plant in turn produces a protein that degrades the effector by autophagy." This is the first evidence of antimicrobial xenophagy in plant-bacteria interactions, he says. Üstün adds that "an interesting aspect of this is that the proteins involved, such as the Xanthomonas effector and the components of the autophagy machinery, are very similar in humans and plants, although they are attacked by different bacterial pathogens." Biologists observe that some proteins have been strongly conserved in very different organisms over the course of evolution.

The new study provides important pointers for further basic research on autophagy and xenophagy in plants. In the long term, these processes could help prevent crop diseases.

Publication:

Jia Xuan Leong, Margot Raffeiner, Daniela Spinti, Gautier Langin, Mirita Franz-Wachtel, Andrew R. Guzman, Jung-Gun Kim, Pooja Pandey, Alyona E. Minina, Boris Macek, Anders Hafrén, Tolga O. Bozkurt, Mary Beth Mudgett, Frederik Börnke, Daniel Hofius, Suayib Üstün: A bacterial effector counteracts host autophagy by promoting degradation of an autophagy component. The EMBO Journal, https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.2021110352