Keep your head down when you're out in the paddock this winter.

That's the tip from The University of Western Australia (UWA) Senior Research Officer Dr Kevin Foster, who said now is a good time to really get to know your paddocks.

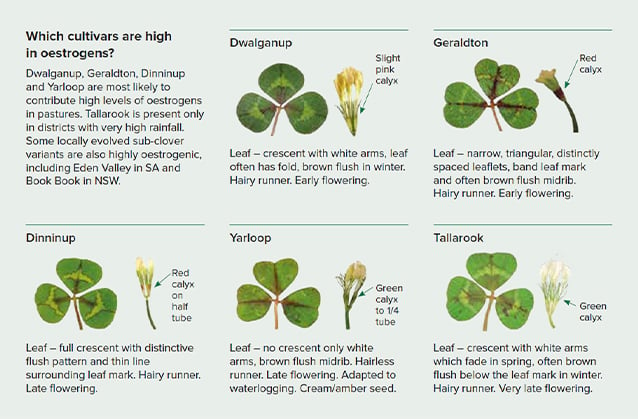

The colder months bring out the most distinguishing features in the leaves of subterranean clover (sub‑clover), making it easier to identify cultivars – including the old oestrogenic cultivars which can negatively affect sheep health and reproduction rates.

With decent autumn rains across much of southern Australia, Dr Foster warns an early break could mean higher intake of oestrogenic clovers and an adverse impact on flock fertility.

Solving a historical problem

In the early 1970s, it was found that many of the sub‑clover cultivars planted widely across southern Australia in the first half of the 20th century contained high levels of an oestrogenic compound, formononetin, in their green leaves.

The release of new, low‑formononetin cultivars in the late 1970s was thought to have resolved the issue.

However, hard‑seeded nature of oestrogenic cultivars has seen a gradual resurgence of the issue in recent years.

In response, MLA Donor Company supported a project (led by Dr Foster and his UWA colleague Megan Ryan) to provide producers and advisors with information and skills to identify and manage the presence of oestrogenic sub‑clover.

The researchers trekked through hundreds of paddocks across southern Australia identifying oestrogenic clovers.

"It's probably the best snapshot of our sub‑clover pastures out there that we've had for many, many years," Dr Foster said.

In analysing hundreds of plant samples, the researchers found around 20% of pastures in southern Australia are dominated by high‑oestrogen sub‑clover, with some districts having a figure of higher than 65%.

The most common oestrogenic clover found in the pasture samples submitted so far has been Dinninup.

What's the damage?

Consumption of older cultivars – Dinninup, Dwalganup, Yarloop, Geraldton and Tallarook – can lead to two forms of infertility in ewes. One is short‑term, with a return of fertility after removal from the high‑oestrogenic pastures, and the other is permanent infertility which increases in severity with continued exposure.

Permanent infertility can also be accompanied by ewe mortality, difficult births and post‑natal lamb mortality.

Even lambs dropped onto oestrogenic pastures may be infertile as maidens. It can also cause udder development problems in maiden ewes and urethral blockages in wethers.

Before this research, many producers and agronomists were not aware of high‑oestrogen cultivars, so poor reproductive performance was often attributed to other husbandry problems.

"When you see the light‑bulb moment that happens when producers realise they have a problem with their sub‑clover, which could've been causing a whole lot of challenges they haven't been able to get to the bottom of until now, it makes you realise this has been such a great investment in research, development and extension," Dr Foster said.

"Our research suggests we need to rule out if it's what ewes are eating in the pasture that's the actual reason for dry ewes."

Think you might have a sub‑clover problem?

If producers suspect they have problem sub‑clover, the first step is to get confirmation.

Seek expert advice and support from your local agronomist or vet, or talk to an agricultural department staff member in your district to help identify cultivars.

After confirming the presence of high‑oestrogenic sub‑clovers, work with your advisors to establish a management plan.

"When prices and demand are strong, it's a good time to allocate funds to invest in improving your pastures, particularly those which aren't supporting your animal enterprise productivity as best they could," Dr Foster said.

Samples of sub-clover can still be submitted for testing as part of this project. Contact Dr Foster for a testing kit, but be quick, as there are limited test kits available for 2020.

Two ways to manage problem cloversIf you have problem clovers in your paddocks, there are two management options. 1. Avoid grazing the paddock with young ewes or lambs and limit grazing by wethers (rams are not thought to be affected). Don't 'grass clean' pastures, as dilution is part of the solution. Oestrogenic clovers need to be less than 20% of overall pasture to avoid livestock health issues. Help livestock avoid the oestrogenic pastures when green by providing other feed sources or using other paddocks. Keep soil phosphorus and sulphur nutrition up to the sub‑clover, as formononetin in the green leaves can increase when clover growth is limited. 2. Go for the ultimate solution and renovate pasture with a low‑formononetin sub‑clover cultivar suitable for your district. New cultivars also have other improved traits to enhance productivity. This is also a good opportunity to improve soil fertility and rhizobia for long‑term productivity gains. Tip: Hay or silage made from green, high‑oestrogenic clover is likely still potent, but sub‑clovers can be safely grazed when they dry naturally at the end of the season. However, ewes should not start grazing until six weeks after drying starts. |