While conservative politicians have a reputation for opposing federal assistance programs for low-income Americans, do those who lean conservative and would benefit from those programs feel the same way?

New research from Manoj Thomas, the Nakashimato Professor of Marketing in the Johnson Graduate School of Management, and Shreyans Goenka, Ph.D. '20, finds that low-income conservatives are just as likely as their liberal counterparts to accept federal assistance, with the caveat that work is a requirement.

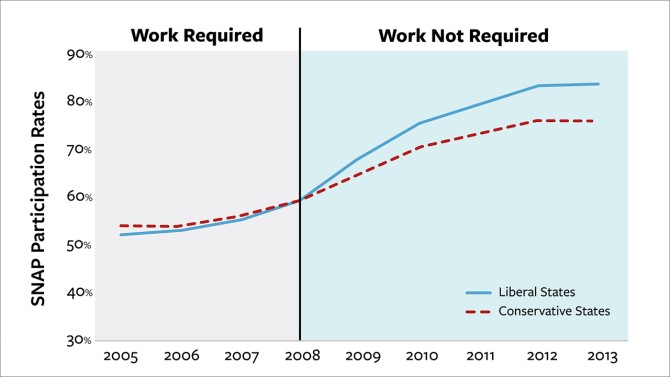

The chart shows SNAP participation rates among liberal and conservative states, both before and after the work requirement was waived in 2009. The states were divided into two equal groups based on Republican vote share.

Goenka is corresponding author of "Are Conservatives Less Likely Than Liberals to Accept Welfare? The Psychology of Welfare Politics," published March 3 in the Journal of the Association for Consumer Research.

For his dissertation, Goenka - now an assistant professor of marketing at Virginia Tech - wanted to explore the idea of "moral heterogeneity."

"It's the idea that, in this case, conservatives and liberals have very different moral outlooks," Goenka said. "Across cultures, people have very different moral values as well. There's no right or wrong, just different groups and they have different moral values."

Exploiting a policy change enacted during the Great Recession, the researchers found that with a work requirement, enrollment in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps) was about the same for liberals and conservatives.

But when the government waived the work requirement in 2009, during the economic recovery period following the recession, enrollment increased at a greater level for liberals than for conservatives. The difference is small but significant; enrollment in liberal states increased by approximately 40%, and by about 29% in conservative states.

"Thanks to Shreyans, I've started looking at the moral influences on economic transactions," Thomas said. "This is one of the most foundational questions that economists and philosophers and others have dealt with. Ideologically, we know that conservatives are against welfare. But many of the people who are against these benefits are people who would not qualify for them."

For their study, Goenka and Thomas first examined state-by-state SNAP participation rates both before and after the work requirement was waived. Participation levels were nearly identical, at around 60%, in the four years (2005-08) when part-time work was a minimum prerequisite for enrollment.

But in the five years after the work requirement was waived (2009-13), participation in liberal states rose to 68% in the first year, and eventually to 84% by year 5.

In conservative states, participation jumped to 65% in the first year, and to 76% in the final two years of the study period.

Goenka notes that the study focuses on state participation, so exactly who was signing up for these benefits is not known. "We're looking at an average for, say, Arizona or Texas," he said, "and not everyone in Arizona and Texas is conservative."

In three subsequent controlled experiments, in which participants were asked to offer views on morality and values as well as federal assistance programs, conservatives were more accepting of government assistance if it contained a work requirement.

Their third study examined how perceptions changed based on marketing materials used to promote the SNAP assistance. They found that if the assistance was promoted as being good for one's community, even with no work requirement, conservatives were as likely as liberals to accept the benefit.

This is one of the goals of their research, Thomas said - getting lawmakers and federal officials to promote assistance programs as being good for one's community, and not just for the individual.

"If you frame it as 'something for nothing,' then it becomes a moral evaluation," he said. "We're hoping lawmakers can see this and reframe promotion of the program as 'something you deserve, something that's good for your country.' Then we hope everybody will accept it."