How an exoplanet survived the rebellion of its home star

When stars, similar to the sun, have reached the end of their lifetime, they inflate into red giant stars. The sun, for example, would then have a diameter hundreds of times larger than today. Whether the Earth will survive this final stage of its home star is uncertain. The planet called Halla around a sun-like star near Polaris, however, was lucky.

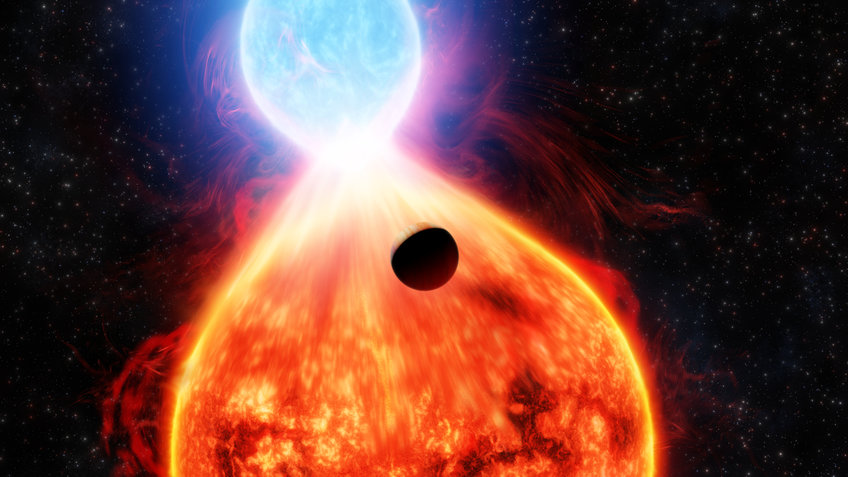

The planet Halla may have once orbited two stars that interacted with one another by mass transfer as depicted. The eventual merger between the stars allowed Halla to escape engulfment and persist around the star that resulted from the merger.

© W. M. Keck Observatory/Adam Makarenko

The constellation Ursa Minor is home to a planet that cannot exist. At far too close a distance, Halla orbits the red giant star Baekdu. When Baekdu inflated in its previous expansion phase, it should have "swallowed" such a close companion. No other planets orbiting similarly close to a red giant star are known. An international team of 42 researchers led by the University of Hawaii examined the unusual pair and presents an explanation for its existence in the journal Nature. A researcher from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Göttingen contributed to computer simulations that led to this explanation. Most likely, Baekdu was born as part of a binary system and therefore never expanded to a size that would be expected for a single star reaching the same evolutionary stage. As a result, Halla may never have been in any danger.

Upon its discovery eight years ago by a South Korean research team, exoplanet Halla was by no means deemed remarkable. Also, the measurements at the Bohyunsan Optical Astronomy Observatory at that time could not firmly identify the evolutionary state of the star. Without knowing of the host star's red-giant stage Halla's close orbit did not surprise. It wasn't until Nasa's space telescope Tess (Transiting Survey Satellite) took a closer look between 2019 and 2022 that it became possible to determine other properties of the star and its companion. Tess routinely records observational data such as characteristic brightness variations caused by stellar oscillations from thousands of stars. With the help of methods of asteroseismology, scientists can then infer the stars' age, mass and evolutionary state. In addition, the W. M. Keck Observatory and the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope on the Hawaiian volcano Mauna Kea also inspected Baekdu and Halla closely.

An unusual pair

Analyses of these data prove Baekdu and Halla to be something of an oddity. Baekdu is one of the fainter objects in the constellation of Ursa Minor and, unlike its "neighbor" Polaris, cannot be seen with the naked eye. It turns out to be approximately 1.5 times heavier than the Sun and must have reached the red giant stage. When stars similar in mass to the Sun reach the end of their lifetimes, a spectacular transformation takes place. The fusion of hydrogen atoms in their core comes to a halt, and the star collapses. The tremendous pressure and heat thus generated in the core causes helium fusion to begin. The star, now called a red giant, inflates to up to a hundred times its original size before shrinking again a little. In the case of Baekdu, the data describe a star that reached a radius of a little more than one hundred million kilometers. Its planetary companion Halla is about one and a half times heavier than Jupiter and orbits its star on a nearly circular orbit at a distance of about 75 million kilometers; this seems entirely impossible.

"Naturally, we wanted to understand how this strange planetary system came to be," said Chen Jiang of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, who was involved in the study. How could the planet survive in such close proximity to a red giant? With the help of extensive computer simulations the researchers weighed various possibilities. As it turned out, the most likely explanation is a turn of events that never placed Halla in direct danger of being devoured by its host star.

From binary star to red giant

Portrayed is the violent merger between two stars that may have formed the helium-burning giant star Baekdu. The merger produces a debris disk that gave birth to the planet Halla.

© W. M. Keck Observatory/Adam Makarenko

"We believe that Baekdu was once a binary star," Jiang said. "When one partner of a binary star expands toward the end of its lifetime, both stars can merge. This stops further expansion," he adds. In this case, the red giant might not have inflated to the orbit of its planet at all. To test this hypothesis, the team simulated this scenario on the computer. The scientists modelled not only the stellar merger itself, but also how this process would affect orbiting planets. Their calculations show that the newly formed star Baekdu would have expanded to a much smaller size - and Halla in turn would have been completely unaffected by the transformation of its star; it would continue to orbit unchanged.

It is also conceivable that Halla did not witness the merger of the double star, but was formed after this process. When two stars merge, rotating disks of dust can form around the new star. As in the early Solar System, this dust can gradually cluster together to form planets.

Neither impossible nor rare

Binary stars are far from rare. On the contrary, most stars are part of such stellar partnerships. And numerous exoplanets orbiting binary stars are also already known. "It is likely that planets orbiting in the close proximity to red giants are not as extraordinary as thought," Jiang concludes. Future space missions and observation campaigns may discover many more.

BK/TB