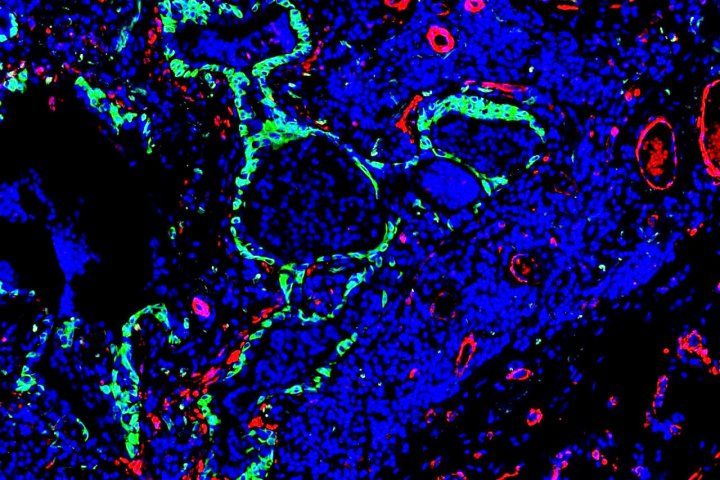

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is characterized by abnormal stem cells (green) present near the scar-forming fibroblasts (red). Image by Monica Cassandras

In response to certain types of injury and inflammation, many organs produce tough scar tissue, a process called fibrosis, which can ultimately lead to organ failure or even death. Fibrosis is such a central component of so many different diseases - from cardiovascular disease to kidney failure - that scientists estimate that it may be the direct cause of 45 percent of all deaths in developed nations.

Now a new study conducted in mice by Monica Cassandras and colleagues at the UC San Francisco Cardiovascular Research Institute (CVRI), published Oct.12 in Nature Cell Biology, highlights the potential of a novel, inhalable regenerative therapy for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

IPF is characterized by progressive scarring - with no identifiable cause - of the sensitive lung tissue responsible for exchanging blood CO2 for oxygen. It affects one in 200 adults over the age of 60 in the United States, which translates to more than 200,000 people currently living with the condition. Each year, approximately 50,000 new cases are diagnosed in the U.S., and as many as 40,000 individuals die from the disease. Currently, there are no therapies that stabilize or reverse fibrosis, only medications that slow the rate of decline.

"Current therapy and pharmacologic strategies target the scarring process in IPF, but little attention has been paid to how scarring alters the natural regenerative capacity of the lung," said Tien Peng, MD, an assistant professor in residence in the UCSF Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care and the principal investigator of the new study.

In cases of fibrosis, researchers have long observed the growth of abnormal trachea-like tissue deep in the lung, a result of dysregulated stem cells, which appears to correlate with the severity of disease in patients with IPF.

Cassandras and colleagues discovered that the same cells that produce scarring in the fibrotic lung also trigger the misbehavior of these abnormal stem cells in areas of damage in the lung.

By examining the signaling between the scar-forming cells and the lung stem cells, the UCSF researchers identified the specific signaling proteins that go awry in the fibrotic lung. They showed that if mice with lung fibrosis inhaled a lab-grown version of a key protein, called bone morphogen protein 4 (BMP4) it could reverse the misbehavior of their stem cells, restore normal lung regeneration, and ultimately improve lung function.

"Local delivery of BMP has been approved for clinical indications such as spinal fusion, but we were surprised and impressed that inhalation of recombinant BMP was able to effectively penetrate through the respiratory tract to instruct proper stem cell regeneration deep in the lung," Peng said. "This demonstrates a potentially novel therapeutic route that appears to maximize treatment efficacy while lowering the toxicity profile for other organs that would be seen with an injectable or oral medication. This also presents a new therapeutic paradigm for lung fibrosis, where the goal is not just to stop the scarring, but also to stimulate native stem cells toward a regenerative program to restore healthy lung."