Your cells constantly generate and conduct electricity that runs through your body to perform various functions. One such example of this bioelectricity is the nerve signals that power thoughts in your brain. Others include the cardiac signals that control the beating of your heart, along with other signals that tell your muscles to contract.

Authors

- Sun-Min Yu

Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Polymer Science and Engineering, UMass Amherst

- Steve Granick

Professor of Polymer Science and Engineering, UMass Amherst

As bioengineers , we became interested in the epithelial cells that make up human skin and the outer layer of people's intestinal tissues. These cells aren't known to be able to generate bioelectricity. Textbooks state that they primarily act as a barrier against pathogens and poisons; epithelial cells are thought to do their jobs passively, like how plastic wrapping protects food against spoilage.

To our surprise, however, we found that wounded epithelial cells can propagate electrical signals across dozens of cells that persist for several hours. In this newly published research, we were able to show that even epithelial cells use bioelectricity to coordinate with their neighbors when the emergency of an injury demands it. Understanding this unexpected twist in how the body operates may lead to improved treatments for wounds.

Discovering a new source of bioelectricity

Don't laugh: Our interest in this topic began with a gut feeling. Think of how your skin heals itself after a scratch. Epithelial cells may look silent and calm, but they're busy coordinating with each other to extrude damaged cells and replace them with new ones. We thought bioelectric signals might orchestrate this, so our intuition told us to search for them.

Almost all the vendors we contacted to obtain the instrument we needed to test our idea warned us not to try these experiments. Only one company agreed with reluctance. "Your experiment won't work," they insisted. If we made the attempt and found nothing worthwhile to study, they feared it would make their product look bad.

But we did our experiments anyway - with tantalizing results.

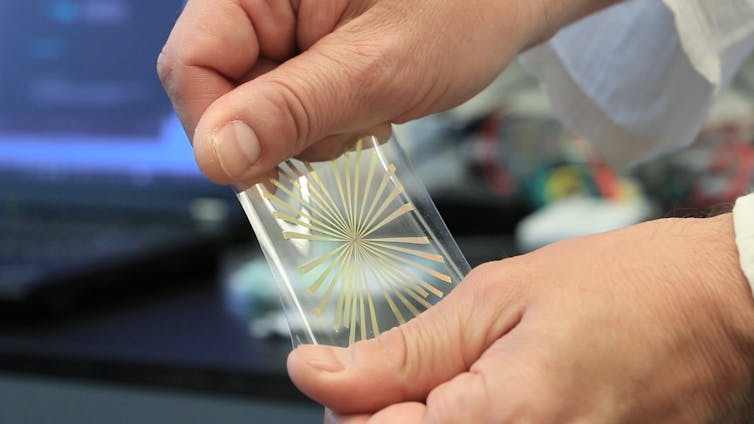

We grew a layer of epithelial cells on a chip patterned with what's called a microelectrode array - dozens of tiny electric wires that measure where bioelectric signals appear, how strong the signals are and how fast they travel from spot to spot. Then, we used a laser to zap a wound in one location and searched for electric signals on a different part of the cell layer.

Several hours of recording confirmed our intuition: When faced with the emergency need to repair themselves, bioelectrical signals appear when epithelial cells need a quick way to communicate over long distances.

We found that wounded epithelial cells can send bioelectric signals to neighboring cells over distances more than 40 times their body length with voltages similar to those of neurons. The shapes of these voltage spikes are also like those of neurons except about 1,000 times slower, indicating they might be a more primitive form of intercellular communication over long distances.

Powering the bioelectric generator

But how do epithelial cells generate bioelectricity?

We hypothesized that calcium ions might play a key role. Calcium ions show up prominently in any good biology textbook's list of major molecules that help cells function. Since calcium ions regulate the forces that contract cells, a function necessary to remove damaged cells after wounding, we hypothesized that calcium ions ought to be critical to bioelectricity.

To test our theory, we used a molecule called EDTA that tightly binds to calcium ions. When we added EDTA to the epithelial cells and so removed the calcium ions, we found that the voltage spikes were no longer present. This meant that calcium ions were likely necessary for epithelial cells to generate the bioelectric signals that guide wound healing.

We then blocked the ion channels that allow calcium and other positively charged ions to enter epithelial cells. As a result, the frequency and strength of the electrical signals that epithelial cells produce were reduced. These findings suggest that while calcium ions may play a particularly crucial role in allowing epithelial cells to produce bioelectricity, other molecules may also matter.

Further research can help identify those other ion channels and pathways that allow epithelial cells to generate bioelectricity.

Improving wound healing

Our discovery that epithelial cells can electrically speak up during a crisis without compromising their primary role as a barrier opens doors for new ways to treat wounds.

Previous work from other researchers had demonstrated that it's possible to enhance wound healing in skin and intestinal tissues by electrically stimulating them . But these studies used electrical frequencies many times higher than what we've found epithelial cells naturally produce. We wonder whether reevaluating and refining optimal electric stimulation conditions may help improve biomedical devices for wound healing.

Further down the road of possibility, we wonder whether electrically stimulating individual cells might offer even more healing potential. Currently, researchers have been electrically stimulating the whole tissue to treat injury. If we could direct these electrical signals to go specifically to where a remedy is needed, would stimulating individual cells be even more effective at treating wounds?

Our hope is that these findings could become a classic case of curiosity-driven science that leads to useful discovery. While our dream may carry a high risk of failure, it also offers potentially high rewards.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.