Saber-tooth cats often conjure images of fearsome predators. But of the nearly 100 unique 'types' of saber-tooths that wandered the earth, researchers have determined that was not always the case.

Larisa DeSantis, paleontologist and associate professor of biological sciences, along with a team of international collaborators led by Christine Janis, professor of earth science at the University of Bristol (UK) have found that the anatomy of the animal Thylacosmilus atrox - a jaguar-sized cat popularly known as the 'marsupial saber-tooth' - suggests it was not nearly as vicious as other creatures with a similar appearance like the North American species Smilodon fatalis, a placental carnivore.

"These saber-tooth marsupial predators are bizarre! What this research teaches us is that we need to look beyond the massive sabers of these creatures, and when we do, we learn that the sabers of Thylacosmilus may have had different functions than that of the best known saber-tooth cats of North America," said DeSantis.

The article, "An eye for a tooth: Thylacosmilus was not a marsupial 'saber-tooth predator'" was published online in the journal PeerJ on June 26.

Despite the apparent similarity of marsupial saber-tooths and saber-tooth cats, marsupial saber-tooths were more closely related to kangaroos and possums than saber-tooth cats. Marsupial saber-tooths were known as the standard-bearers of convergent evolution - the independent evolution of unique organisms resulting in similar traits. Bats, birds and butterflies are three living species that represent the convergent evolution of flight. Each has wings despite not sharing a common ancestor that flew.

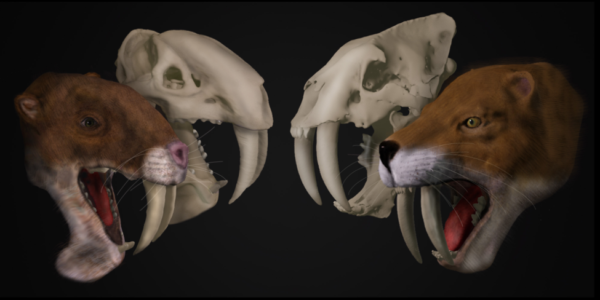

The researchers performed a series of statistical comparisons on the skull and teeth of the marsupial saber-tooth against living big cat species and a selection of saber-toothed cat fossils. Their comparisons, along with biomechanical and detailed dental studies were used to confirm the collaborators' hypothesis that while remains of the marsupial saber-tooth may appear similar to other saber-tooth cats, it was a very different animal indeed.

"Previous studies by other researchers have shown Thylacosmilus to have had a weaker bite than Smilodon," said contributing author Stephan Lautenschlager, lecturer in paleobiology at the University of Birmingham (UK). "But what we can show is there was probably a difference in behavior between the two species: Thylacosmilus' skull and canines are weaker in a stabbing action than those of Smilodon but are stronger in a 'pull-back' type of action. This suggests that Thylacosmilus was not using its canines to kill with, but perhaps instead to open carcasses."

"It has impressive canines, for sure: but if you look at the whole picture of its anatomy, lots of things simply don't add up," said Janis. "For example, it just about lacks incisors, which big cats today use to get meat off the bone, and its lower jaws were not fused together." In addition, the canines of Thylacosmilus were different from the teeth of other saber-toothed mammals, being triangular like a claw rather than flat like a blade.

"Putting all of the jigsaw puzzle pieces together, Thylacomilus may have been ripping open carcasses with their massive canines and subsequently slurping out the guts of their prey," said DeSantis.

"The near lack of incisors, soft food eating evidenced by the microscopic wear patterns on their teeth and other features provide cause for this sort of interpretation."

"The skull superficially looks rather like that of a saber-toothed placental," said Borja Figueirido, a professor in the department of ecology and geology at the University of Málaga (Spain) and a co-author of the paper. "But if you actually quantify things, it becomes clear that Thylacosmilus' skull was different in many details from any known carnivorous mammal, past or present."

"It's a bit of a mystery as to what this animal was actually doing," said Janis. "But it's clear that it wasn't just a marsupial version of a saber-toothed cat like Smilodon".

Researchers are continuing to put the pieces together with clues from the present-day Argentinian plains where the marsupial saber-tooth roamed five million years ago. In the ecosystem of the past, predators of the day were huge, flightless "terror birds", leaving researchers to try to understand the role of mammals at that time.