Newport, R.I., is known as a playground for the super-rich, an oceanside city where tourists gawk at opulent Gilded Age mansions, chase their oysters with a glass of bubbly, and gaze at yachts slipping in and out of the harbor. What many don't realize is that through much of the 18th century, Newport was the largest slave trade port in North America.

One of the city's most prominent early slave owners was Rhode Island Deputy Governor Jonathan Nichols, Jr., whose harbor-front mansion, now known as Hunter House, still stands. A merchant, Nichols' fortune came from the triangular trade: the selling of New England rum to buy African slaves, who were then sailed to the Caribbean and again sold for the sugar and molasses needed to make rum.

Today, the Georgian Colonial-style house is operated as a museum by the Preservation Society of Newport County, the same nonprofit that operates the Breakers and Elms mansions just across town.

In September 2020, MaryKate Smolenski (GRS'27) became a Preservation Society research fellow, and she was tasked with codesigning a new narrative and tour of the house that would be honest about its past and would delve into the lives of all its residents. Shuttered during the pandemic, Hunter House reopened in August.

Smolenski, a PhD candidate in American and New England studies, plans to research Revolutionary-era female loyalists and material culture at BU. She considers herself a social historian, interested in the lived experiences of everyday people, she says, "not just the white male owners." Through her research, she aims to give equal weight to the stories of the enslaved people, free people of color, women, and children who lived at the house, those whose stories are typically not told in the narratives of historic houses, or even in general history.

"It's important to accurately reflect Newport's past," she says. "There were a variety of religions and racial groups here in Newport-in fact, almost 15 percent of people were of African descent. We want visitors to hear stories of family tragedy and resistance and be able to find a connection to their own lives in some way. That makes a visit to Hunter House meaningful."

Help from the Vanderbilts

In the early 19th century, US Senator William Hunter purchased the house and lived in it the longest (hence the name). The original 1748 structure was expanded throughout its life, and also used as a home base for the French army during the Revolutionary War, as a convalescent home, and as a convent. In the 1940s, Hunter House was once again put up for sale, and a small group of concerned citizens, worried it would be torn down, bought the house to save it from demolition. Although the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 was not yet in existence, the group thought to create a long-term solution, looking at initiatives like Colonial Williamsburg and Old Sturbridge Village as models.

Hunter House was recently used as a filming location for Julian Fellows' new HBO drama The Gilded Age. One of the rooms was used as the Pennsylvania office of lawyer Tom Raikes.

The Preservation Society of Newport County was founded in August 1945 with the goal of raising funds and restoring Hunter House, and three years later, Newport grand dame Gladys Vanderbilt, Countess Széchenyi, stepped in and provided financial assistance. Her generosity allowed the Preservation Society to lead tours of the mansion and use the proceeds for the restoration work. The Preservation Society copied this model when it purchased the Elms, the Breakers, and other summer "cottages" in the years that followed. For almost 70 years, Hunter House, designated a National Historic Landmark in 1968, was open to tours, with a special focus on the furniture and decorative arts that filled the space.

Detective Work

Smolenski grew up in nearby Middletown, R.I., and led tours of the Breakers and other Newport mansions as a part-time job in high school and college. While earning her master's in history and museum studies at Tufts University, she applied to become a research fellow at Hunter House. The fellowship, which wrapped last month, included assessing its collection and designing a new guided tour.

Working with Catherine Doucette, another research fellow, Smolenski started by evaluating all the previous Hunter House research and tour scripts. For example, a tour script written in 1986 describes the role of resident Joseph Wanton, Jr., in the sea trade, but Smolenski and Doucette discovered that "sea trade" actually involved the transatlantic slave trade. They spoke to some of the home's previous research fellows and reviewed the first Hunter House exhibition, in 1953, put together by Ralph Carpenter, an enthusiastic collector who was dedicated to preserving Newport's Colonial furniture and architecture. They also created an online survey to poll past visitors, who overwhelmingly said they would like to learn more about the house's occupants, not hear just about furniture and crafts.

(left) This saw is believed to have been owned by Newport cabinetmaker Robert Lawton, Jr. It was donated to the Preservation Society by Ralph Carpenter, who directed the refurbishing and furnishing of Hunter House. (right) A sampler sewed in 1764 by the then 12-year-old Mary Emmes. At that time, needlepoint was a way for young girls to practice their alphabet and stitches. It is captioned with the verse "Care use with all thy power To Serve God every hour."

To uncover the story of who lived at Hunter House, Smolenski combed (both in person and virtually) wills, account books, bills of sale, financial documents, letters, photographs, and more at the Newport Historical Society, the Rhode Island Historical Society, the Rhode Island State Archives, and local libraries.

"Some of the documents that I viewed had been looked at in the past to learn more about the decorative arts of the house, such as probate inventories, but the names of the enslaved individuals were overlooked," Smolenski says. One example was the will and probate inventory of Nichols, the home's first owner. Previous researchers had noted what decorative arts Nichols owned at the time (two marble sideboards), but they failed to mention that the probate inventory also listed seven enslaved people: Cambridge, Toby, Joe, Lucas, Phyllis, Maude, and Dick.

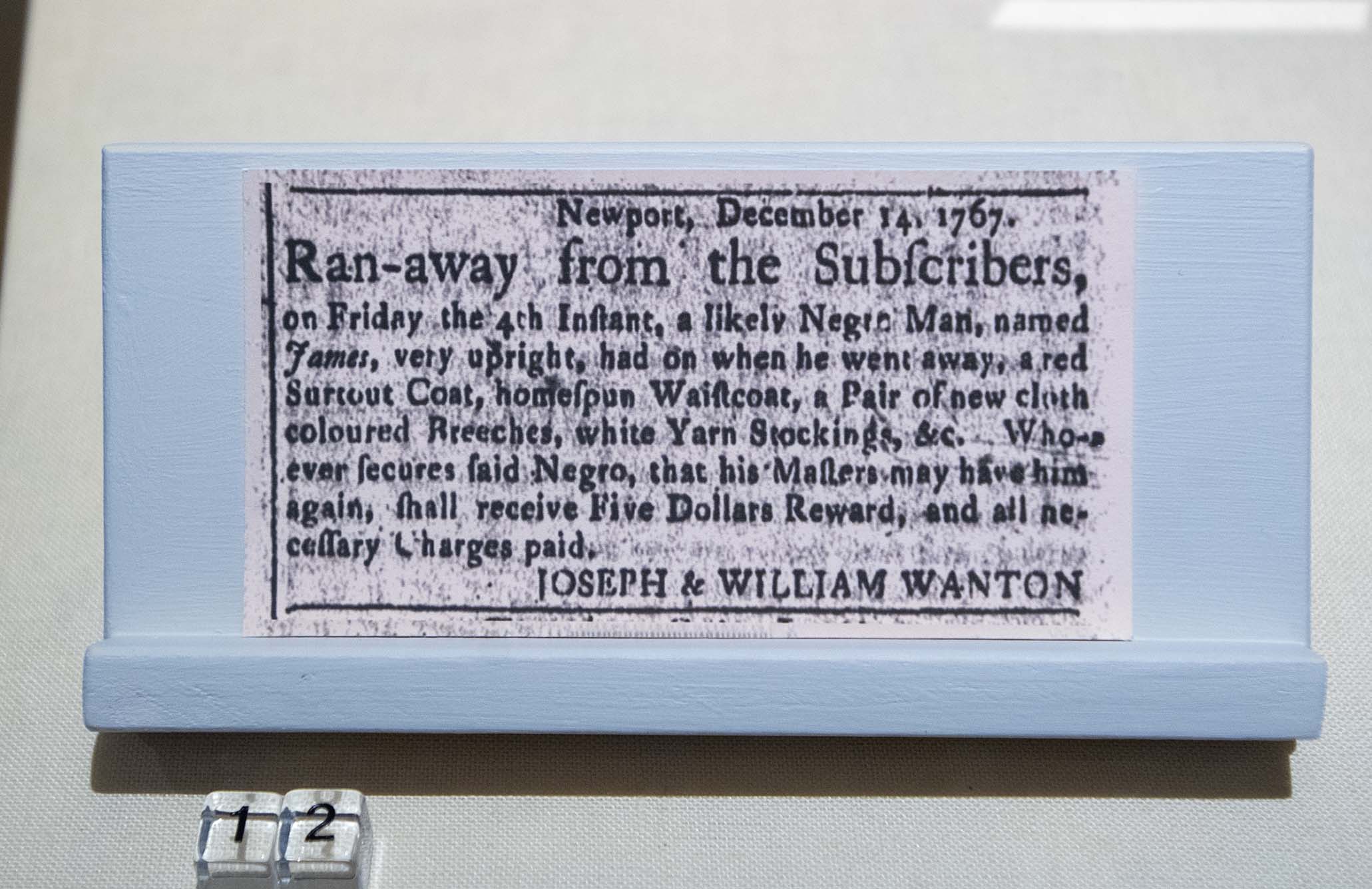

Nichols' enslaved men most likely worked on his wharf, she says, unloading cargo like tea and sugar, while the women would probably have performed the home's domestic work. Smolenski ultimately found records of eight slaves or free people of color not previously known to have lived at Hunter House. One nugget of information she came across was a bounty advertised in The Newport Mercury for a runaway slave named James (see image below).

Smolenski compares her work to that of a detective. "I really like going into the archive and reading through document after document just to find a little snippet," she says, "and then trying to pull together all these different sources to tell as full of a narrative as I can, and really honoring people whose voices were lost in the past."

A New Tour

Smolenski and Doucette ultimately decided to have their new 50-minute tour move chronologically through the house, as opposed to the many house museums that focus on one owner. They also decided to convert a room into a new orientation gallery, where visitors can find introductory texts, a timeline of ownership, and display cases with items such as china and silverware.

In the script of her new tour, Smolenski informs visitors of slavery's connection to some of the museum's displays, including its fine silver, paintings, and furniture. "What's interesting in regard to Newport is that [slave traders] brought a lot of children, unfortunately, mostly because they apprenticed them to learn all these crafts," she says. "And so enslaved craftspeople worked in every industry in Newport-stone carving, silversmithing, furniture-making. They were really skilled laborers, not working out on a larger plantation like in the South or in Rhode Island's Narragansett County plantations, but working in workshops in people's homes."

The Hunter House tour ends in an upstairs bedroom. There, tour guides ask visitors to look upward at an empty frame hanging above the fireplace, meant to signify that there are many stories of this house that have yet to be discovered, or sadly, have been lost forever.

"We tried to bring home on the tour that it was not this great peaceful past that sometimes people like to think," says Smolenski, who hopes to one day become a museum curator. "It was a difficult time for many people who lacked rights, freedom, and economic ability. And so we try to really honor that. And that's why we end with our empty frame. We tell a lot of new stories on the tour. But there's certainly still more left unsaid."

Smolenski's work was partially funded through a Dean F. Failey Grant from the Decorative Arts Trust.