While the urgent reduction of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gas emissions is needed to curb climate change, there is broad agreement by the scientific community for the need to remove CO2 already in the atmosphere. An article published in Frontiers in Climate, by an international team of researchers, including two University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa oceanographers, explains the need to assess the potential of ocean iron fertilization (OIF) as a low-cost, scalable and rapidly deployable method of marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR).

"Open ocean iron addition experiments have been done before and we know that this might not work at the scale needed to meaningfully reduce atmospheric CO2," said Angelicque White, a UH oceanography professor. "Inaction however is not a path forward, and it is far deadlier than any open ocean OIF. The climate crisis cannot be ignored, and Hawaiʻi has already been impacted—sea level rise, ocean acidification and ocean warming are all pressures we feel close to home. Rational, ethical, responsible and transparent science is needed to determine if mCDR will buy us time; assuming of course that we also reduce emissions."

What is ocean iron fertilization?

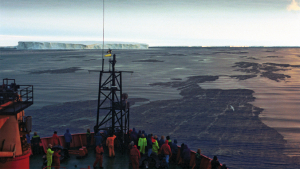

OIF is a technique that adds small amounts of iron, an essential element for life, to the ocean's surface to promote the growth of marine plants, or phytoplankton. This growth removes CO2 from the atmosphere, and as plankton die or are eaten, transfers some of that carbon as sinking particles for storage in the deep ocean. While large amounts of iron naturally enter the ocean, OIF is an effort that could speed up that process.

"We still have a lot to learn about what happens if we add iron to the ocean—how long will it remain in ocean water, what kinds of plankton it will stimulate, and how much carbon storage this can actually yield," said Nick Hawco, assistant professor in oceanography at UH Mānoa. "Similar to how we test new medicines in clinical trials, some of these questions can only be answered with carefully controlled ocean trials."

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine identified OIF as an emerging climate solution, and more than 400 scientists signed onto a letter calling for expanded mCDR research.

"This is the first time in over a decade that the marine scientific community has come together to endorse a specific research plan for ocean iron," said lead author, Ken Buesseler, executive director of the Exploring Ocean Iron Solutions program, and Senior Scientist in the Marine Chemistry and Geochemistry Department at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

In the study, researchers focus on five key activities: field studies in the northeast Pacific Ocean; regional, global, and field study modeling; testing various forms of iron and delivery methods, which have differing advantages and disadvantages; advancing monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) for carbon and eMRV (which focuses on examining ecological changes); and advancing social science and governance efforts to go hand in hand with the physical science efforts.

Portions of this content courtesy of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.