Antidepressants can play a crucial role in improving the mental wellbeing of people with depression. For many, if not most patients however, getting the right medication is a matter of trial and error.

But WA Health researchers are now hopeful that with the help of a patient's DNA, they may soon be able to take the guesswork out of prescribing these drugs.

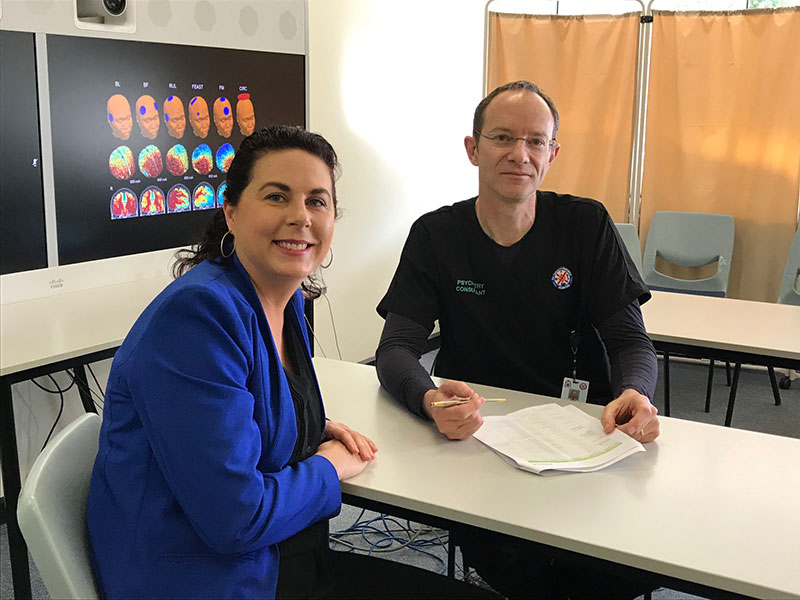

Office of Population Health Genomics Director Kristen Nowak, North Metropolitan Health Service psychiatrist Sean Hood and Clinical Lead for Primary Care Integration Dr Jacquie Garton-Smith are part of a new $2.95 million multi-centre investigation that will determine whether first-line medications have greater chance of succeeding if their prescription is guided by the patient's individual genetic make-up.

Professor Hood, who is also head of psychiatry at the University of Western Australia, reveals that around half of patients with moderate to severe depression report no benefit from first-line medications and that as many as two thirds fail to achieve long-term remission from their depressive symptoms.

"This is really concerning because it can often take weeks or months to get the right medication and dosage for a severely depressed patient," Professor Hood said.

"There is a risk that these patients might have a bad reaction to a medication or become really unwell and require hospitalisation. Many could abandon their medication altogether or even attempt suicide.

"That is why it is so important we get better at prescribing drugs that will be effective from the outset."

The study, which will also run in NSW and Victoria, will recruit patients who have been newly diagnosed with moderate to severe depression or who have had a relapse following remission from their condition.

On joining the trial, all participants will undergo a brain scan and provide a buccal swab (cells collected from inside the cheek).

These cells will be used in a multi-gene test, otherwise known as a pharmacogenomic (PG) test, which will survey around a dozen genes that are known to play a role in metabolism (a biochemical process that affects the way an individual processes medications).

Dr Nowak said the test essentially provided a small snapshot of the patient's DNA code.

The test would enable a customised report to be generated for every participant in the trial, indicating their likely response to different medications and dosage levels, based on their genetic profile.

A personalised treatment plan will also be prepared for each participant, but only half of these plans will be guided by patients' PG results – the rest will be developed following current standard-of-care guidelines only.

The treatment plans will be reviewed by a national panel of experts. Until week 12, neither the patient nor their treating doctor will know to which group they have been assigned.

The study will enable the researchers to assess whether patients given PG-guided care had significant earlier benefit over those receiving standard care.

The study will also evaluate the cost effectiveness of PG-guided care.

Dr Nowak said that although PG testing had been available for many years and there was growing recognition of its value, it had not been adopted widely for guiding medication choice and dosing.

"Given the time, cost and patient impacts of potentially having to try several medications – and the fact PG testing has now come right down in cost and turnaround times – we think there is real value in assessing the potential benefits of more personalised care," she said.

In addition to their main study questions, the researchers plan to investigate the effectiveness of using PG-guided treatment in conjunction with brain scans and also see if using artificial intelligence to analyse the study data can fine-tune their prescribing ability even further.

The trial, which has received funding from the Commonwealth Government's Medical Research Future Fund, will enrol 550 patients – 275 of whom will be from WA. They will be enrolled through two participating local hospitals – Sir Charles Gairdner and Hollywood Private.

Other WA collaborators on the project are the University of WA, medical insurer HBF Health Limited, mental health group Meeting for Minds, and the Perron Institute.

The study will begin in late 2020, once ethics and governance approvals are obtained locally and nationally.