It's hard to imagine now, but for almost 1,000 years, pregnant women in England could avoid the death penalty just by virtue of being pregnant. A pregnant woman sentenced to death would receive a stay of execution until the baby was born. It was called "pleading the belly" and often resulted the death sentence being reduced to a less severe penalty once the pregnancy was over.

Author

Alice Neikirk

Program Convenor, Criminology, University of Newcastle

Of course, anyone could say they're pregnant without actually being with child. So how did courts determine whether it was true?

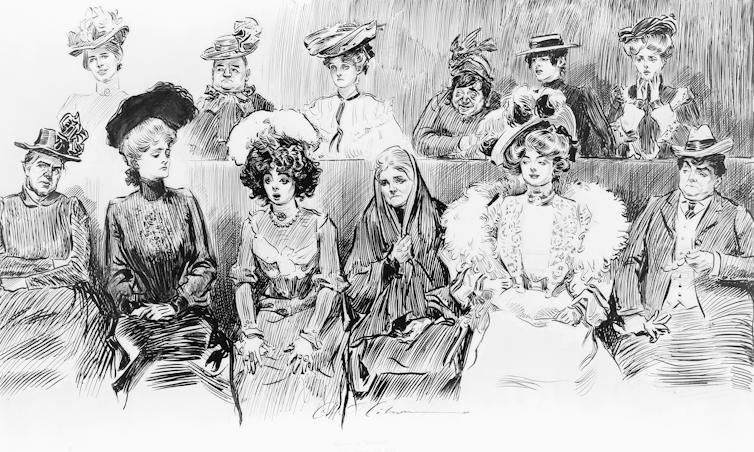

It was standard practice to assemble all-female juries, called "juries of matrons", to determine whether a woman was pregnant and could therefore avoid hanging for capital offences. These were also features of Australia's colonial legal system, with juries of matrons being used in trials until the early 1900s.

Exploring the history of these juries reveals how the roles of women in our legal systems have changed over time. It also shows a shift in beliefs about who is an expert in the female body, and who gets to make decisions about it.

Highly regarded medical experts

All-female juries existed as early as 1140 in England and persisted until 1931. Their role in the courts was highly regarded. They were medical experts. If they found the woman was "quick with child" (pregnant), their findings were not disputed.

In addition to determining whether a woman was pregnant, they helped evaluate inheritance claims, examined females to determine whether they bore the physical marks of witchcraft, and decide whether a woman accused of infanticide had given birth. They provided expert medical testimony for the courts but were not necessarily midwives.

These women were respectable, law-abiding women. Similar to their male counterparts, serving on a jury was a high-status privilege. There is evidence that from 1233 until 1435 in Newcastle upon Tyne, an official pool of matrons existed. They held an appointed position in the court.

Australia's first civilian jury

Historically, we tend think of juries as only being comprised of males, yet these all-female juries also existed in colonial America and in Australia and New Zealand until the early 1900s. In fact, Australia's first civilian jury was an all-female jury of matrons.

In 1789, Ann Davis was found guilty of stealing items of clothing. This theft was a capital offence. She "pleaded the belly".

An all-female jury of matrons was convened to assess her claims, marking the first time a civilian jury was used in Australia. More than 200 years ago, the 76-year-old forewoman of that jury found, "Gentlemen! She is as much with child as I am". Her plea unsuccessful, Davis became the first woman hung in Australia.

Another notable example of pleading the belly was Elizabeth McGree in South Australia. In 1883 she was charged with killing a man. The "powerfully built man" had been drinking with her husband that evening. After the husband passed out drunk, the man left the house, only to return in the early hours of the morning.

The forensic evidence demonstrated he kicked in the door, strangling McGree while also attempting to rape her. McGree's 12-year-old son hit the man on the head with a hammer in an effort to stop the assault. After the initial blow, McGree started to beat the man with the hammer (who got up after her son's first blow and wandered outside, promising not to touch her again) and stabbed him with a knife.

McGree was found guilty, despite the forensic evidence, largely because she allowed the man to drink liquor at the house with her husband. She was sentenced to hang.

Once found guilty, she pleaded the belly and a jury of matrons was called. They determined she was "quick with child", and she dodged the noose. She later gave birth to her child in Gladstone Prison. Her death sentence was commuted to ten years.

If the pregnancy resulted in birth, a reprieve from the noose was fairly common. This raised the concern among men that women might falsely plead the belly to avoid a capital offence. They worried a jury of matrons, being "naturally" sympathetic, might grant them a reprieve from death.

While there is scant evidence this was the case, to address this concern, the laws around pleading the belly stipulated this plea could only be made once. If a pregnant woman was granted a reprieve from death to have the baby, she could be executed for any future crime - even if pregnant.

Women "too irrational" for courts

By the late 1800s, suspicion that juries of matrons were "soft" and that women were abusing the belly plea merged with concerns that women were "too irrational, too burdened by suckling infants, too sexually ignorant or too easily corrupted by sexual knowledge" to have a role in courts.

These concerns, along with the rise of medical professionals and the invention of the stethoscope, shifted the balance of power away from the jury of matrons and towards male medical officers.

Who had expert knowledge of the female body shifted. Until this point, women determined whether the fetus was alive by examining the women and feeling for signs of fetal movement or "quickening". Quickening was considered the moment the fetus becomes animated with a soul, and thus fully human.

Now, the stethoscope could detect a fetal heartbeat. This was considered a more reliable method of establishing pregnancy.

The jury of matrons disappeared from the courts in Australia. It was another 50 years before women in Australia would be allowed to serve on juries. Progress, in terms of female representation, is rarely linear.

Juries of matrons were an extraordinary example of women having an official role in a justice system otherwise dominated by men. The examples of women pleading the belly provide a glimpse the role and interactions women had in Australia's early legal systems.

![]()

Alice Neikirk receives funding from the History Council of South Australia.