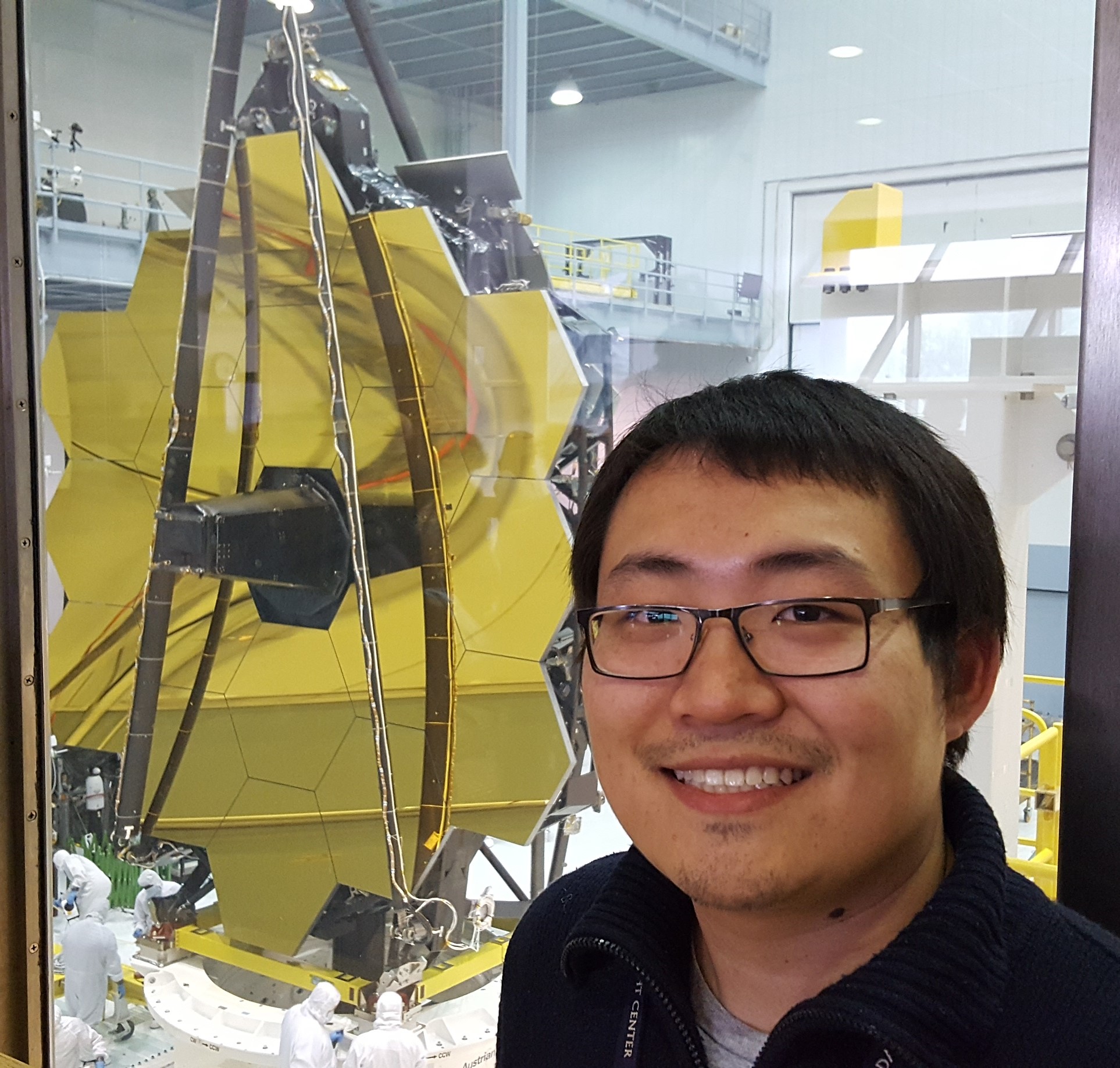

As team lead of the Instrument Design Laboratory, Kan Yang turns science concepts into engineering reality.

Name: Kan Yang

Title: Team Lead of the Instrument Design Laboratory

Formal Job Classification: Technical Manager

Organization: Instrument Systems and Technology Division, Engineering and Technology Directorate (Code 550)

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard?

I work with a team of scientists and engineers to design space flight instrument concepts. I love seeing the newest ideas from scientists and having a say in a technical design that matches their scientific vision.

What is your educational background?

In 2008, I got a bachelor's in science and engineering from the University of Michigan. In 2010, I got a master's in aerospace engineering from the University of Maryland.

Why did you come to Goddard?

I came to Goddard in 2010 because I always wanted to work for NASA. When I was a kid, I watched documentaries about the Hubble Space Telescope being assembled. I saw the people working in the clean room and wanted to be one of the technicians in clean room suits assembling the telescope. Also, I've always been fascinated by astronomy, ever since my parents took me to an observatory at a young age to see Comet Hale-Bopp hanging in the sky.

What are the highlights of your initial thermal work at Goddard?

I started at Goddard as a thermal engineer doing thermal analysis of the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) satellite. I moved on to the Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer (LADEE) mission where I analyzed the temperatures of the satellite sitting within the rocket at NASA's Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia. We launched at the end of summer, which can get hot, so we were concerned about whether the HVAC system could keep the satellite cool enough on the launch pad. After LADEE launched, we noticed a specific instrument heating up more than expected so we had to analyze how to change our operational methods at the Moon to prevent overheating, all while the satellite was already on the way from the Earth to the Moon. This also occurred during the 2013 government shut down: a no-pressure-at-all type of situation!

What was one of your most exciting moments working on the James Webb Space Telescope?

I have spent the bulk of my career working on thermal analyses for the James Webb Space Telescope. For six years, I had one task: to take the "cold" half of the telescope, which contained the large mirrors and sensitive instruments, and figure out how to cool it down to the temperatures it would see in space, about minus 240 degrees Celsius (or about minus 400 degrees Fahrenheit), so that we could test it here on Earth in the conditions it would see in space.

We tested James Webb at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston in the largest thermal vacuum chamber in the world. It is eight stories tall and 55 feet wide. It took about 100 days to execute this test, including cooling it to negative 240 degrees Celsius, doing our optical and thermal check-outs at this temperature, then heating it back to room temperature. During our testing, we were hit by Hurricane Harvey. We rode out the storm for five days, including all 51 inches of rain: the most rain Houston had ever had. We worried about losing power. Our tests are under vacuum, like in space, and if we had lost power, the vacuum pumps would no longer work and the rapid increase in pressure would have damaged the telescope. We very luckily we did not lose power! We were also worried because we use liquid nitrogen to cool the thermal vacuum chamber and we constantly needed trucks to deliver and replenish the liquid nitrogen, since there was only a limited amount that could be stored next to the test chamber. Truck drivers heroically drove through the flooded streets to deliver us the necessary liquid nitrogen before we ran out.

How do you handle such on the job pressure?

I always work with a great team. You can make much better decisions when you can talk with your team and listen to their perspectives. Once we have good technical judgement and can develop a plan for a way forward, it gives everyone a sense of calm. I was also fortunate to have been mentored by some incredible individuals at Goddard, and to have worked on projects with great leadership and project management, like on James Webb. Receiving valuable advice from these mentors and observing great leadership in action has allowed me to grow as an individual and more easily handle on-the-job pressures.

You became deputy team lead of the Instrument Design Laboratory (IDL) in 2019. How did you maintain the IDL's collaborative dynamic through the pandemic?

In 2019, I became the deputy team lead because I wanted to expand my horizons into a more systems engineering-type role, and the IDL offered a great opportunity to do so. In 2022, I became the team lead. The IDL began in 1999 at Goddard and gives engineering realism to scientists' ideas. We can accomplish this through instrument design studies, where the scientists and engineers dedicate time to closely collaborate with each other and design an instrument which can make the scientist's intended measurement from space.

Until 2020, the IDL did everything in-person, performing conceptual design studies sort of like a "Skunk Works." We had a team of up to 30 people working in a room on the same design and engineering solution to realize the scientists' vision. When the pandemic hit, the then-team lead and I had to figure out how to do the same work virtually. Virtual collaborative engineering is hard. We spent a lot of time on video chats discussing what processes would work best to effectively communicate the information among all the engineers.

We had two challenges. First, how do you replace hallway conversations and in-person interactions with something as regimented as a virtual meeting, where only one person can talk effectively at a time? Second, how do you make sure that each engineering discipline engineer's concerns are heard by everyone?

We set up a lot of channels and virtual chat rooms for engineers to communicate directly with each other. We had to carefully plan times where we would speak about a particular topic, and make sure the discussions didn't overlap or that the same engineer had to be in two different conversations at the same time. I felt like a wedding planner. Our IDL leadership team had to listen to everyone's concerns and capture their design decisions, and then relay those effectively to the entire team so that we were all on the same page. We found new ways of working with each other that we had never thought about in the 21-year history of the laboratory before the pandemic. Since we are now working in a hybrid environment, our new tools still apply.

What are some of your proudest moments as team lead of the IDL?

I am very proud of the sheer variety of instruments we have been able to design for Goddard, ranging from astronaut-deployed instruments for the Artemis Moon missions, to the next generation of large space-based telescopes, instruments that monitor Earth's changing climate, and an astronaut-operated instrument within the International Space Station.

One of the coolest instruments we developed was a chemical sensor for a probe that will drop into Saturn's atmosphere. Another fascinating instrument will measure the ice particles shooting out of geysers from one of Saturn's ice-covered moons, Enceladus, which is a candidate destination for the search for life elsewhere in the solar system.

What are your goals as the vice-chair of the Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) Employee Resource Group?

Our major goals for AANHPI Employee Resource Group (ERG) are threefold: we aim to increase diversity in leadership, tackle specific issues and challenges affecting AANHPI employees, and showcase our pride in our heritage with events and celebrations. Regarding leadership, we encourage our AANHPI workforce to join leadership programs and have invited leaders within the AANHPI community to speak to their career journey, one of whom was a former state senator from Hawaii. Regarding challenges, we work to eradicate barriers which prevent diverse candidates from advancing in their careers, and recommend focus areas to senior leadership to address AANHPI-specific concerns. Regarding events, we host a few celebrations and educational offerings at Goddard and across NASA each year. This may take the form of inviting chefs to give cooking demonstrations, planning dance performances, or welcoming speakers to share their stories and traditions. We feel this is a wonderful way to connect with our colleagues and honor the cultural richness of our NASA workforce. I feel very fortunate to be working with an amazing ERG chair to achieve these goals, as well as with outstanding individuals in our leadership team and ERG membership.

When you do outreach, what is your message?

I do outreach at elementary schools, high schools, middle schools, and colleges. I tell them that even though the emphasis is on STEM, NASA needs all sorts of people from diverse backgrounds. What's truly important is that you are passionate about what you do. You do not have to be an engineer or scientist to work at NASA. Also, not everyone at NASA looks or thinks the same. We need different opinions to make NASA effective.

Is there anyone you want to thank?

I'd like to thank my parents. When I was 3, my parents and I immigrated to this country from China. We came with hardly anything. It is through their extreme hard work that I was able to pursue my dreams and have the life that I have right now.

I'd also like to thank my wife. She is always diligent and supportive of our family, and encourages us to become our best, authentic selves. Our family continues to thrive because of the sacrifices that she makes.

What do you do for fun?

I have a 5-year-old and really enjoy being a dad. I love seeing things from his perspective.

I also enjoy traveling and cooking many different foods. I make some pretty good pasta sauce, and after years of tweaking my fried rice recipe, I think I've found the key to a delicious one. My wife, who is of Colombian heritage, is also teaching me how to cook Colombian food.

What is your "six-word memoir"? A six-word memoir describes something in just six words.

Be kind and do great things.