Rochester political scientists explain why people do and don't exercise their right to vote-and the implications of that choice for democracy.

It's election season, when candidate lawn signs sprout in yards and political messaging seeps into news feeds. With early voting underway in a contentious presidential race, many Americans are preparing to visit their polling place to cast their ballot (and score their "I Voted" sticker). Some will party (or not) like it's 1907, if one can trust the Election Night in the Memorial Art Gallery at the University of Rochester.

Yet for other voters, Election Day is just another Tuesday.

What does voter turnout mean?

Technically, "voter turnout is the number of people who cast ballots in any given election," says Mayya Komisarchik, an assistant professor of political science at the University of Rochester.

In the United States, the voting-eligible population comprises citizens of the right age, who are not convicted of a felony-though this depends on state law-and not mentally incapacitated. "But it's hard to get that granular with numbers, so the voter turnout rate is typically calculated as the number of ballots cast divided by the voting-age population," she says. "If high turnout is the harbinger of a healthy democracy, we want a high percentage of voter turnout."

Since 1980, voter turnout for US presidential elections has fluctuated between 50 to 65 percent of eligible voters-with the exception of 2020, when it reached a record high of 67 percent. (Midterm elections draw significantly fewer voters.)

"Turnout in the US is not super-high relative to other democracies, like in Australia, where voting is compulsory with a fine for not participating," says Komisarchik.

Even without a slap on the wrist, why aren't more US citizens voting?

"Given that we're talking about 51 different electoral systems (each state plus Washington DC) with multi-pronged processes, various restrictions, and lots of contestation, the voter turnout rate doesn't surprise me," says James Druckman, the Martin Brewer Anderson Professor of Political Science. "States vary dramatically in terms of their registration laws, early voting policies, access to polls, even when absentee ballots are counted."

Scheduling is also a factor: In some places, local elections are timed to coincide with midterm or presidential ones, while in other places they are staggered in different years.

Add to this tangle the country's history of constricted ballot access and voter suppression, through legal means and otherwise: literacy tests with subjective scoring, character witnesses (also subjective), and recent challenges to the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965. The finer points of "electioneering" can even penalize distributing water at a polling line.

In the lead-up to Election Day, here are several key points about voter turnout and why it's important.

Voter "decline" is often really voter disenfranchisement.

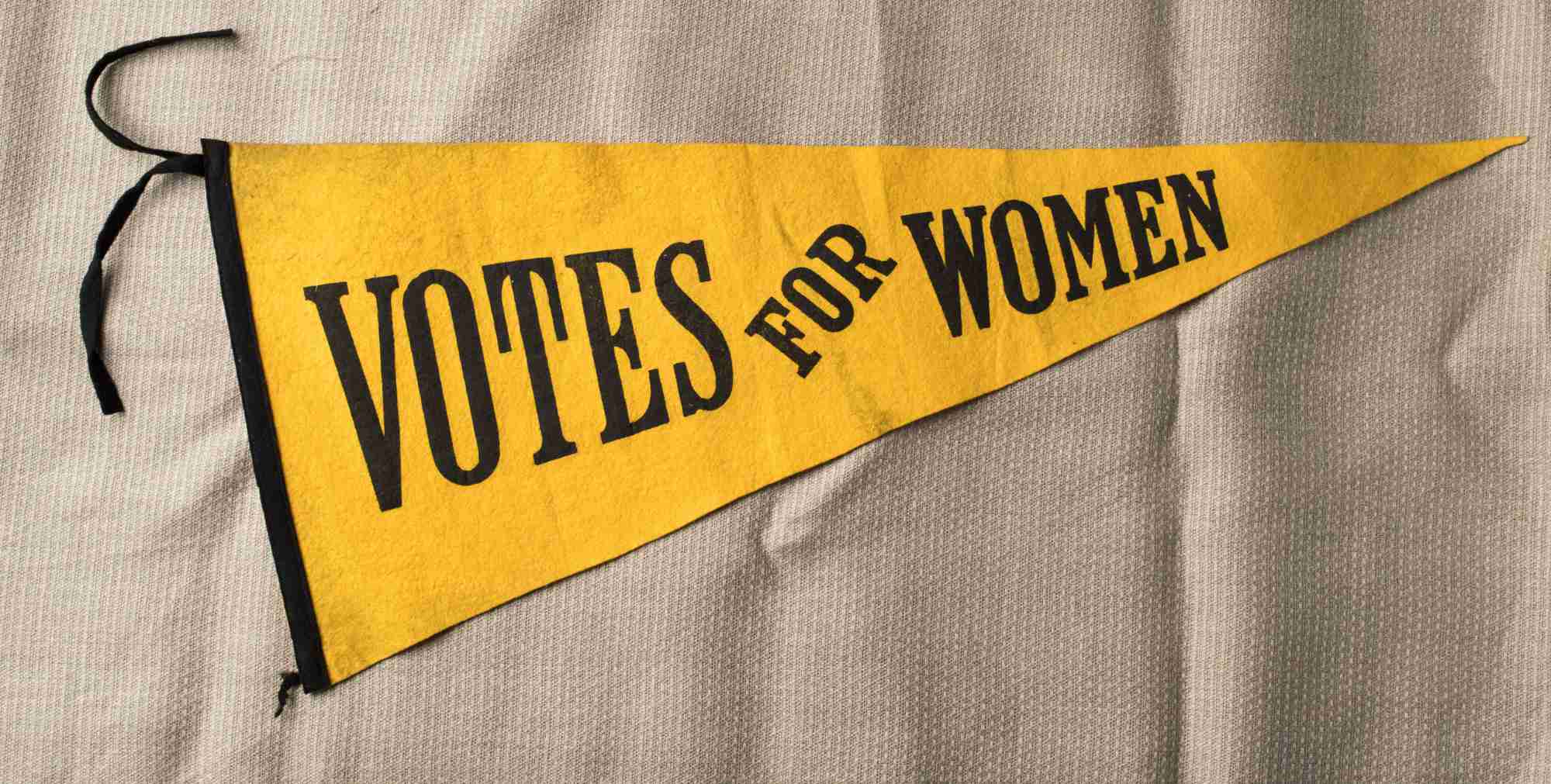

Extending the franchise-or giving more people the right to vote-is one way to influence voter turnout.

In 1870, the 15th Amendment to the US Constitution acknowledged the right of formerly enslaved African American men to vote. Fifty years later, in 1920, the 19th Amendment was ratified, legally guaranteeing American women the right to vote, a longstanding goal of the women's suffrage movement. (Susan B. Anthony was a key player in the movement. On November 5, 1872-well before the 19th Amendment's ratification-Anthony marched to the polls near her home in Rochester, New York, demanding to vote in the presidential election. She cast her vote, but was subsequently arrested, charged, and indicted.)

Conversely, disenfranchising people can also affect voter turnout.

"Because we often divide voters by the entire voting-age population, voter turnout appeared to decline through the 1970s, 80s, and 90s," says Druckman. "In reality, this is explained by the growing disenfranchisement rate of felons."

Only in Maine, Vermont, and Washington, DC, do people convicted of a felony never lose their right to vote. In other states, convicted felons are ineligible to vote either while incarcerated, for a period of time after release, or indefinitely.

When it comes to the calculus of voting, participation trumps "pivotality."

In US elections, some states are reliably "blue" or "red"-that is, the results of the state elections tend to be more Democratic or Republican, respectively. By contrast, "purple" or "swing" states are those where either the Democratic or Republican candidates could win a statewide election. In these so-called battleground states, the difference between winning and losing can come down to a few thousand-or even hundred-votes.

Why, then, would anyone in a blue or red state bother to cast a ballot, knowing their vote isn't pivotal to the election results? Is the act of voting an irrational one if you know your vote isn't pivotal?

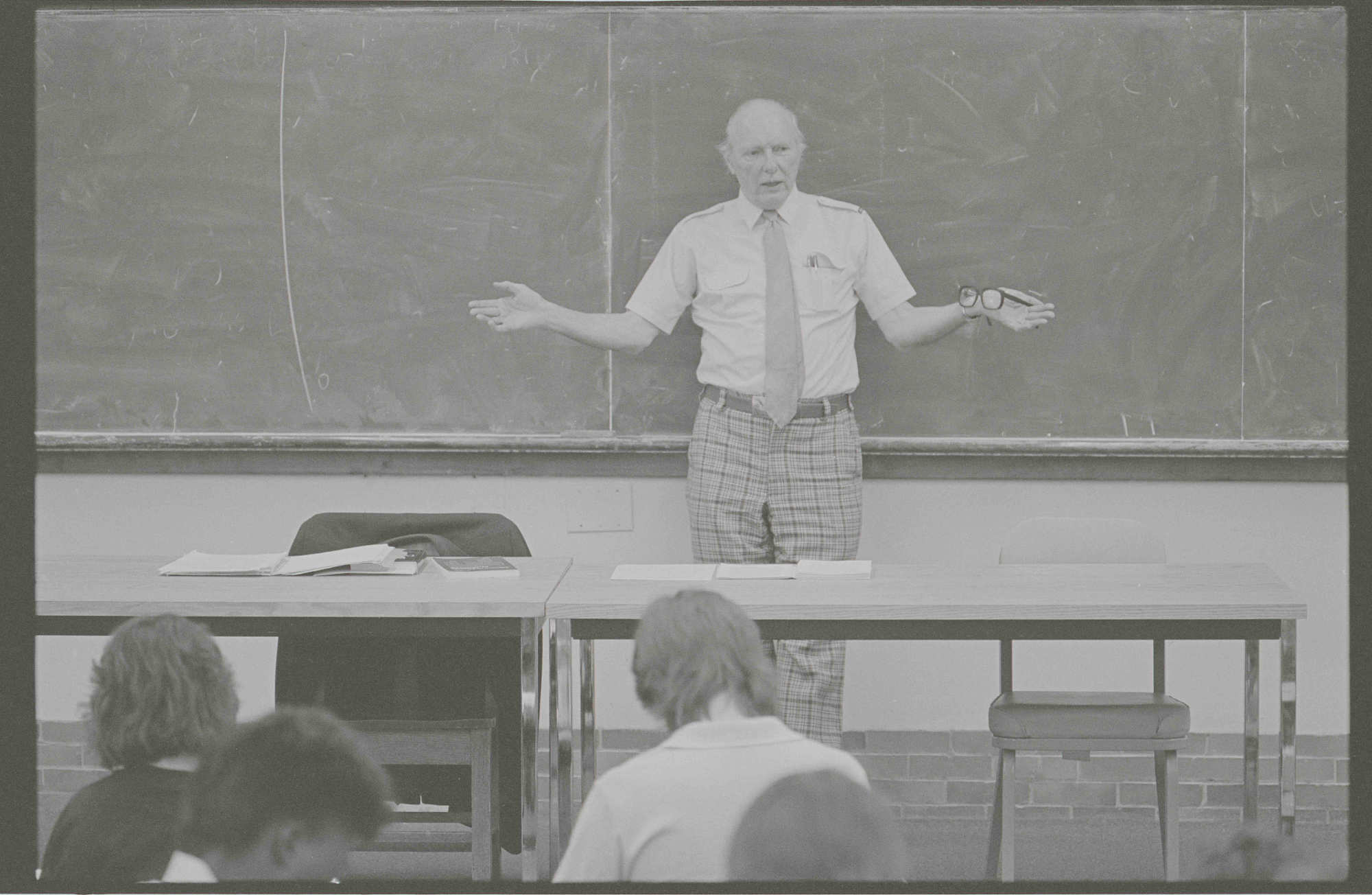

Enter the rational choice theory, a scientific model of political behavior that assumes people make decisions based on their calculations of costs and benefits. William Riker, an American political scientist at the University of Rochester from 1962 to 1993, is considered the founder of rational choice theory. He used economic and game-theoretic approaches to develop mathematical models of politics, including the Riker-Ordeshook theory of the calculus of voting. In doing so, he founded an entirely new subfield of political science in the 1960s-one that continues to influence the discipline today.

"Rational choice theory is an umbrella term for considering instrumental motivations that voters might have. In other words, what compels a person to vote?" explains Scott Tyson, an associate professor of political science at Rochester.

Those motivations could vary anywhere from getting personal satisfaction from participating in the democratic process to thinking your vote will make the difference in a particular election. The latter "is a narrower definition of instrumentality," says Tyson. "What is the likelihood that I am pivotal in this election? If my vote is pivotal for Candidate A, that means half of all voters will vote for Candidate B. And that means that public opinion is more divided than I thought. So, when my vote 'matters' the most, my knowledge that it's 'right' may be the least secure."

Voting behavior has evolved from private decision to team sport.

"More recently, voting has taken on an event-based, participatory aspect," says Tyson. There's a difference between attending a concert or game in person versus streaming it on YouTube. "It's just not the same," he says. Likewise with voting today.

The aforementioned Riker-Ordeshook model of political science-also called the paradox of voting-ascribes most of the benefit of voting to the act itself, rather than to the outcome of the election. Even when a voter knows they won't change the outcome, they still get some value from the act-whether that's securing the coveted "I Voted" sticker or posting a selfie on social media (after clearing the electioneering zone, of course).

According to Tyson, today's political advertisements reinforce the notion of voting behavior as a team sport or stadium concert, rather than reflective decision-making. "Very few ads seem designed to persuade independent voters to cast their vote one way or another," he says. "Instead, they seem to ask: 'Are you going to turn out for your candidate on Election Day? Will we see you in the arena?'"

From drizzle to deluge, the weather forecast matters for voter turnout.

"On a rainy and cold day, people are less likely to stand outside the polling place in long lines," says Komisarchik. And when handing out water and snacks is perceived as risky, people may not wait outside on sweltering Tuesdays, either.

Extreme weather events can impact voting behavior even more profoundly. "Sometimes there are natural disasters right around Election Day, like tornadoes, where officials need to consolidate voting places as shelters," says Komisarchik. For example, during the Super Tuesday Democratic Party presidential primaries in 2020, severe tornadoes in Nashville, Tennessee, forced the closing and consolidating of polling stations, leaving voters and election officials scrambling to navigate both dangerous conditions and thorny logistics.

Younger people tend to vote less (sorry, Bernie).

"Voting habituates," says Druckman. "The key determinant of voting in any given election is whether you have voted before."

So, which voters reliably show up to exercise their civic duty?

"In general, the people who are most likely to turn out-and turn out in most elections, from presidential to midterms to primaries to local races-are college-educated suburban homeowners," says Komisarchik. "They are stakeholders, who have lived somewhere for a long time and put down roots."

Turnout rates also increase along with voters' level of education.

Younger voters between ages 18 and 29, conversely, tend to vote less. "This is the bane of Bernie Sanders' campaign. If your life is in flux without a fixed address, you're less likely to vote."

People over the age of 45 are the highest-propensity voter, Komisarchik says. And despite efforts to enforce (and protect) the Voting Rights Act, "racial gaps do persist. By and large, it's still the case that white voters are most likely to turn out." Data shows that the most significant drop-off is for Hispanic voters, specifically for midterm elections.

Low voter turnout used to benefit Republicans. Now it favors Democrats.

"Political scientists used to think that low-turnout elections were marginally better for the Republican party," says Komisarchik. "Historically, it was the case that all college-educated homeowner suburban votes were Republican. But in the Trump years, there has been a realignment and those places now tend to go Democrat."

One of the largest advertising investments late in Trump's campaign, she notes, has been anti-transgender attack ads. Komisarchik says, "That does not look like an effort to win back suburban voters who value affordable childcare or accessible health care."

This realignment will likely persist for a while, she says, with political, societal, and historical implications still playing out in real-time.

Same-day registration boosts voter turnout.

Same-day registration allows voters to register and vote at the same time, usually on Election Day itself. This voting option, currently available in 23 states and Washington, DC, is the strategy that "consistently has the most positive impact, from what I've seen," says Komisarchik.

For states without this option, campaigns should try the opposite tactic. According to Komisarchik, research on voter turnout suggests that one way to reduce the "mental load" for voters is to encourage them to make a written plan in advance.

"This includes when they will vote, the confirmed location of their polling place, and how they will get to the polls. Providing them with rides, registration information, and other means to reduce their 'mental load' will also help," she says.

Without a paper trail, trust in elections and democracy suffers.

If voting migrated online for convenience, would turnout improve? Maybe-but don't count on seeing a ballot box icon next to the Amazon button on your home screen.

"The tricky thing about voting is that if we removed all logistics and other 'costs,' it would be easier," Komisarchik allows. "People could vote from the convenience of their homes. However, we also need elections to be secure, auditable, and verifiable-with a 'paper trail.' Cybersecurity experts tell us that the most secure way to vote is on paper."

The tangible evidence of a paper trail makes it more difficult for a foreign power or bad actors to interfere, she explains, while simplifying post-election audits. "They would have to break into polling stations and steal the physical ballots, as opposed to remotely hacking a server. In a world of eroding trust and mounting disinformation, paper ballots actually give us security."

Meet your experts

James Druckman

Martin Brewer Anderson Professor of Political Science

Martin Brewer Anderson Professor of Political Science

An expert in political behavior and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Druckman studies public opinion formation, political polarization, political and scientific communication, political psychology, and experimental and survey methods. He has published approximately 200 articles and book chapters. His latest coauthored book, Partisan Hostility and American Democracy: Explaining Political Divisions and When They Matter (University of Chicago), was published in 2024.

Mayya Komisarchik

Assistant Professor of Political Science

Assistant Professor of Political Science

Komisarchik's research interests cover representation, voting rights, race and ethnic politics, policing, immigration, and political incorporation. Her recent work has addressed changing electoral rules in southern counties in the wake of the Voting Rights Act, the lasting effects of Japanese-American internment, representativeness in policing, and the political incorporation of immigrants to the United States. Her work appears in the American Journal of Political Science and the Journal of Politics.

Scott Tyson

Associate Professor of Political Science

Associate Professor of Political Science

Tyson's research focuses on formal political theory, political economy, conflict, authoritarian politics, external validity, and experimental design. He has authored or coauthored scholarly articles that have appeared in the Journal of Politics, American Journal of Political Science, American Political Science Review, Political Science Research and Methods, and PS: Political Science and Politics.