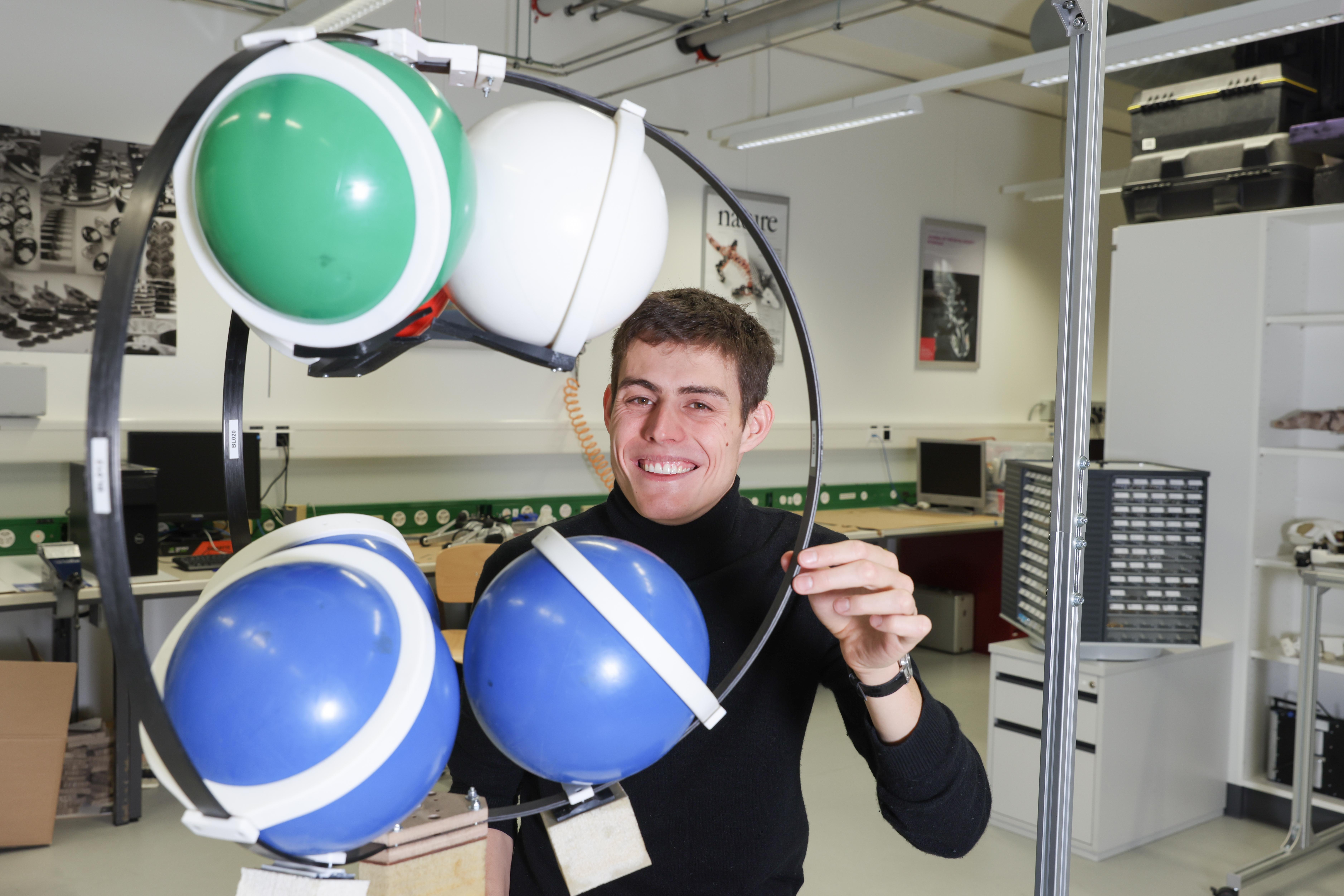

Lucas Froissart carries out tests on the RTS site © Alain Herzog 2022 EPFL

EPFL engineering student Lucas Froissart designed an exoskeleton capable of propelling robot explorers into subsurface tunnels on the moon.

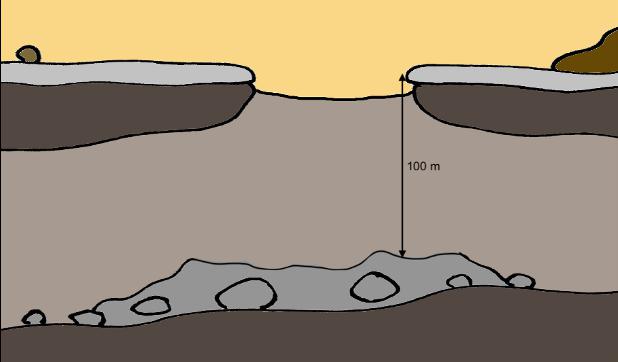

A hundred meters below the surface of the moon lie caves untouched by humans. They were discovered about ten years ago, but space agencies want to send robots to investigate these mysterious cavities before astronauts venture in. "On the moon's surface, the temperature is 150 degrees above zero during the day and 150 degrees below zero at night," says Lucas Froissart, who recently completed a Master's degree in mechanical engineering at EPFL. "In these subterranean caves, which can be reached through natural, vertical pits, the temperature is -30 degrees and there's no radiation. Since the climate is constant and tolerable for human beings, these tunnels could conceivably serve as base camps."

Round robots

During his Master's program, Froissart landed an internship at the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). Because of the pandemic, however, he couldn't go to Tokyo. He ended up doing his internship work in Professor Auke Ijspeert's lab, collaborating with his Japanese colleagues by video conference.

Froissart's instructions were brief: he had six months to design a mechanism capable of propelling six explorer robots through the lunar tunnels. "I didn't even get to see what these robots looked like. I was just told that they were like a gymnastic ball in terms of weight, size and rigidity," he says. So Froissart bought some gymnastic balls and set to work building an exoskeleton that could hold six robots.

How high the drop?

"The exoskeleton is designed to be dropped into a lunar pit, which is about 100 meters long," says Froissart. "When it touches the ground, three explorer robots are propelled at a 45-degree angle in order to go as far as possible into the cave. The other three are released on the spot to collect immediate data." His system tests had to take into account not only the height of the fall, but also the weightlessness and lack of air resistance on the moon. Froissart calculated that he had to drop his exoskeleton from a height of 20 meters on Earth in order to simulate lunar conditions.

Froissart found the ideal testing location while walking on the EPFL campus: the RTS construction site next door. After apprising the construction manager of his project, he was allowed to use one of the scaffolds to drop his exoskeleton. "The site workers even made me a sandpit with a ton and a half of sand to receive it," he says. A few hundred tests later, he was finally successful, as the balls were propelled several meters the moment the structure hit the ground. He received positive feedback from JAXA, which planned to pursue his work. "We may see it on the moon in a few years' time," he says.

Froissart, who always wanted to work in the space industry, recently found a job building satellites and rocket nose cones in Zurich: "My experience with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency landed me this job."