Elevated levels of lead have been found in samples of honey from hives downwind of the Notre-Dame Cathedral fire, collected three months after the April 2019 blaze.

In research outlined in Environmental Science & Technology Letters, scientists from UBC's Pacific Centre for Isotopic and Geochemical Research (PCIGR) analyzed concentrations of metals, including lead, in 36 honey samples collected from Parisian hives in July 2019.

While all the honey fell within the EU's allowable limits for safe consumption, honey from hives downwind of the Notre-Dame fire had average lead concentrations up to four times that of samples collected in the suburbs or countryside surrounding the city, and up to three and a half times the amount found in Parisian honey pre-dating the fire.

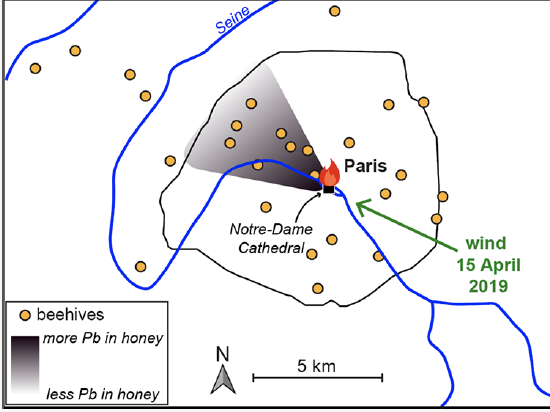

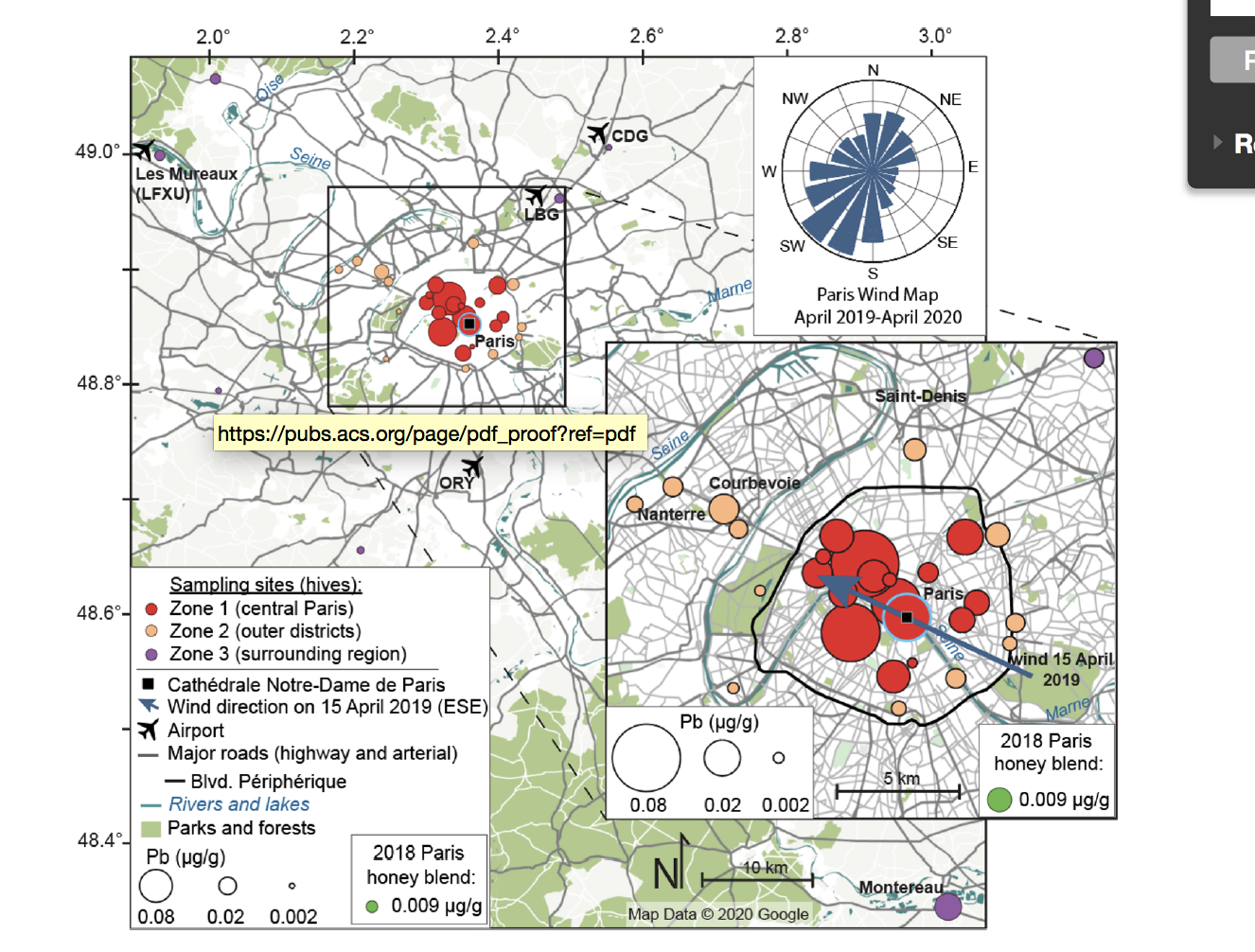

"Because of the way the wind was blowing the night the fire burned, the direction that the smoke plume traveled is well-defined. The elevated lead concentrations were measured in honey that was collected from beehives within that plume footprint," said Kate Smith, lead author of the study and PhD candidate at PCIGR.

Wind direction on the day of the fire, April 15, 2019.

Map showing sampling sites and wind direction on day of fire.

The researchers compared honey collected after the fire to a Parisian honey blend from 2018 and to samples from the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region collected in 2017. The highest concentration of lead, 0.08 micrograms per gram, was found in a sample from a hive located within five kilometres west of the cathedral. The pre-fire Parisian honey had 0.009 micrograms of lead per gram, and honey from the Rhône-Alpes had 0.002 to 0.009 micrograms of lead per gram. The EU's maximum allowable lead content is 0.10 micrograms per gram for syrups, sweeteners, and juices.

Cathedral roof and spire contained tonnes of lead

Lead was a common building material in Paris throughout the time of construction of Notre-Dame, which dates back to the 12th century. The cathedral's roof and spire contained several hundred tonnes of lead. While most of it simply melted in the fire, some flames reached temperatures high enough to aerosolize various lead oxides, and an estimated 180 tonnes of lead remain unaccounted for in the rubble.

"The fact that the Notre-Dame spire was loaded with lead was absolutely a unique research opportunity," said co-author Dominique Weis, director of the PCIGR. "We were able to show that honey is also a helpful tracer for environmental pollution during an acute pollution event like the Notre-Dame fire. It is no surprise, since increased amounts of lead in dust or topsoil, both of which were observed in neighbourhoods downwind of the Notre-Dame fire, are a strong indicator of increased amounts of lead in honey."

Because honey bees forage within a two- to three-kilometer radius of their hive, honey can provide a useful localized snapshot of the environment. As the bees forage, they collect dust and airborne particles, which make their way into the honey.

Hives on Notre-Dame sacristy rooftop.

Photo of Notre-Dame hives featuring co-author Sibyle Moulin and scaffolding in background.

Photo of some fire damage and melted Pb (lead) that oozed out of a hole in the wall.

Smith and Weis worked with Parisian apiary company Beeopic, which manages around 350 hives throughout the city, and collected the samples for this study. Honey was sampled directly from each individual hive and sent to the PCIGR's clean laboratory for testing.

This study marks the first time this method of heavy-metal analysis using honey has been used in a megacity, and one with a history of lead use dating back for millennia. It came out of previous work by Smith and Weis, in which they measured trace amounts of metals in honey from urban beehives in six Metro Vancouver neighbourhoods, demonstrating the use of bees as an effective biomonitor.

"The highest levels of lead that we detected were the equivalent of 80 drops of water in an Olympic sized swimming pool," said Weis. "So even if the lead is relatively elevated, it's still very low. It's actually not higher than what we see in honey from downtown Vancouver. In a city as young as Vancouver, we are able to trace sources of the metal using distinct isotopic signatures. In Paris, however, the long history of lead use throughout the city made the interpretations more challenging. This provides an important consideration for future lead sourcing studies in very old cities."

"Honey Maps the Pb Fallout from the 2019 Fire at Notre-Dame Cathedral, Paris: A Geochemical Perspective" was published July 23 in Environmental Science & Technology Letters.