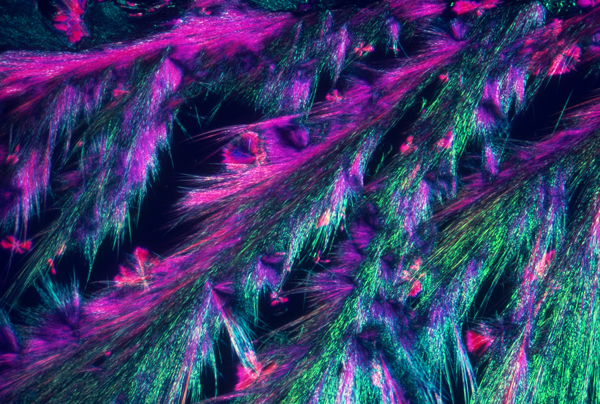

Figure 1: Polarized light micrograph of crystals of the amino acid tyrosine. RIKEN researchers have found that limiting the dietary intake of tyrosine in female adult fruit flies improves their starvation resistance and longevity. © M. I. WALKER/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Feeding female fruit flies a diet low in the amino acid tyrosine improves their ability to endure food shortage, reduces their reproductive output, and causes them to live longer, RIKEN researchers have found1. The findings could have implications for how diet affects human longevity and reproduction.

Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins, which are in turn essential for many cellular processes. They are classed as non-essential if the body can make them or as essential if they can only be obtained from food.

Restricting protein intake, and thereby reducing the intake of essential amino acids, is known to trigger various metabolic and behavioral changes, such as slowing the metabolic rate and increasing lifespan. But less is known about what role non-essential amino acids play in this scenario.

Previous research on fruit-fly larvae has suggested that reducing dietary intake of the non-essential amino acid tyrosine has significant effects. But researchers from RIKEN and the University of Tokyo wanted to further explore this effect in adult flies.

Among non-essential amino acids, tyrosine is unique in that it is the only one that is produced from an essential amino acid, phenylalanine.

Tyrosine plays a crucial role in the production of neurotransmitters and hormones. "Tyrosine is also converted into the neurotransmitter dopamine," explains Fumiaki Obata of the RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research. "So tyrosine is very important."

Obata and his team fed adult female fruit flies a range of diets that were each low in one specific non-essential amino acid.

The fruit flies on the low-tyrosine diet lived longer than those on diets with normal levels of tyrosine. The tyrosine-starved flies also had smaller ovaries and lower fertility. Furthermore, they changed their dietary preferences toward foods that were higher in protein, suggesting they were adapting better to the starvation conditions.

However, these changes were only seen when the tyrosine-deprived flies were on the low-amino-acid diet; they didn't show any of the same starvation responses when they were put on a normal diet that deprived them only of tyrosine.

Obata was surprised by the results. "Because tyrosine can be manufactured in the body, I wasn't expecting to see such an impact from dietary restrictions," he says. "Halving the amount of tyrosine in their diets triggers something beneficial for them."

Obata and his team now intend to investigate whether other animals such as mammals show similar effects when deprived of tyrosine.