Sleeping under the stars, food roasting over a crackling fire, a coffee pot perched on a burning log - such idealized scenes continue to drive demand for recreational camping, with some 40 million Americans expected to visit campgrounds this summer.

But it was a very different reality that captivated Martin Hogue, associate professor of landscape architecture in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, during his first camping experience in 2000 - one that launched more than a decade of research into camping culture, culminating in his latest book, "Making Camp: A Visual History of Camping's Most Essential Items and Activities."

At a commercial campground near Badlands National Park, a circled number on a map directed Hogue to one of more than 100 sites for tents and RVs. Guests could access restroom and laundry facilities, the internet and amenities including a convenience store, swimming pool, miniature golf course and even a dog park.

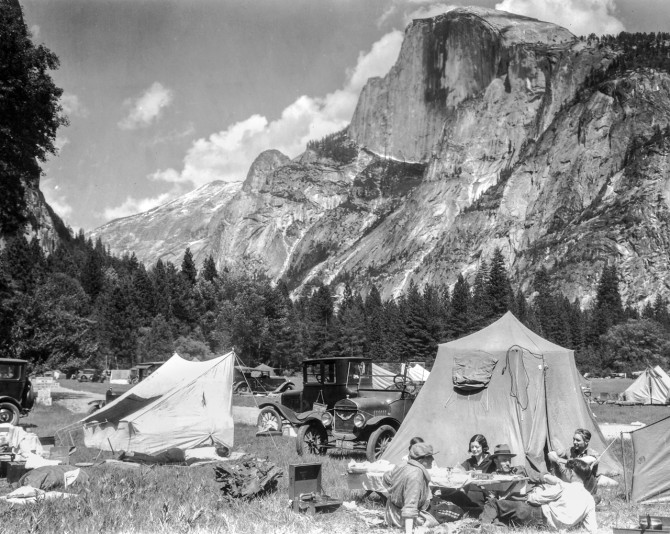

"Overflow Crowd of Campers in Stoneman Meadow," Yosemite National Park (1915), photographer unknown.

"There was a profound disconnect between the expectation of what I thought camping might be like - a mental image largely fueled by dramatic movie scenes depicting settlers on the Western range sleeping under the open night sky - and what the experience actually turned out to be," Hogue said. "I'm fascinated by that disparity."

In "Making Camp," Hogue explores campgrounds' history and evolution over 100 years as spatial settings - from open fields into often dense, highly structured spaces with infrastructure to manage vehicle traffic, utilities and trash.

Eight narratives examine key components used to "make" a camp and the camping experience, from tents and sleeping bags to elements in place when guests arrive: the campsite, fire pit, picnic table, campground map and systems for delivering water and disposing of garbage. Each narrative is accompanied by extensive image collections telling the story through photographs, architectural drawings, patents, paintings and advertisements.

Read perhaps by the light of a campfire or at a picnic table, the book aims to inspire reflection on the "intricacies, ironies and rewards of the camping experience with each trip," Hogue writes.

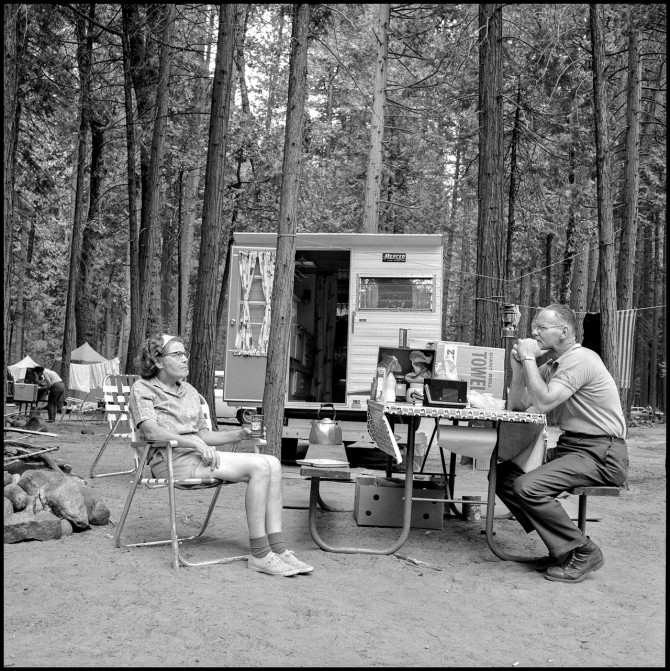

"Photograph of a Couple at their Campsite" (1965), Bruce Davidson, from "Yosemite Campers" series.

An early campsite from the Adirondacks, where recreational camping first took off after the Civil War, depicts the ideal of rugged self-sufficiency in nature: men outside a canvas tent cook over a fire built from felled trees. But by 1965, photographer Bruce Davidson presents a less romanticized experience: families lounge in lawn chairs outside camping trailers with coolers, gas grills and televisions; their campsites - at iconic Yosemite National Park, though they could be anywhere - separated by bedsheets.

Fast forward to 2008: a photo of a camper working at a laptop on a picnic table. Hogue notes that campsites at many state and national parks now are booked online six months in advance, a trend that raises concerns about equal access to an activity notably lacking in diversity.

While there's irony in "roughing it" with so many comforts from home, "Making Camp" makes clear that's nothing new. Early camps at Yosemite and Yellowstone National Park resembled modern "glamping," featuring hardwood floors and comfortable beds in tents erected a short distance from hotels. And an 1862 painting of a lakeside Adirondack camp - among the images that helped grow camping's popularity - shows a man in a formal dinner jacket drinking wine while hired guides catch and grill fish.

"Have we traveled so far," Hogue asks, "between then and now?"

Hogue previously explored camping's rituals in "Thirtyfour Campgrounds," a photographic survey of nearly 6,500 American campsites. More recently, as an artist in residence at Stone Quarry Hill Art Park in upstate New York, he created a summer camping program that is now entering its fifth season.

Modern recreational camping may represent a "carefully staged illusion of discovery and dwelling in the wilderness," Hogue writes. But as they thread poles through tents, lay out sleeping bags or light fires to cook outdoors (even the most charred hotdog invariably tastes better, he joked), campers seeking a closer connection to nature retain an important participatory role.

"You may have to squint a bit to not see your neighbors, to not be aware of how urban some of the largest campgrounds are," Hogue said. "But you're still allowed a degree of agency that gives you the sense that you're making something. It's those little rituals that enable you to claim the site and the experience that add meaning to being out there."