On paper it is recycled, but in reality enormous quantities of plastic waste from the Netherlands end up in Asian seas. Researchers from the Leiden Institute of Environmental Sciences charted the fate of plastic food packaging waste from the Netherlands. They published their results on July 8 in the scientific journal Resources, Conservation & Recycling.

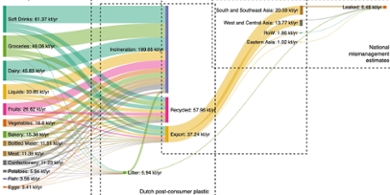

The core of the problem with plastic waste: we produce far more plastic than we can process in our recycling facilities. We, therefore, ship a considerable amount of the waste to countries outside the EU. 'We count these exports as part of the recycled share, but in practice they can end up in landfills or be mismanaged. There, the environment has free rein to drag the plastic into the oceans' explains the lead author Nicolas Navarre.

Complex trade patterns mapped for the first time

'It used to be sent to China, but they banned the import of plastic waste because the quality was too poor to be recycled. Now we largely send it to Turkey and Malaysia but they simply are not equipped to handle our waste either.' Navarre analyzed these complex trade patterns and estimates that over 38 kilotons of plastic waste from Dutch food packaging ends up outside the EU every year and estimates that around 13 kilotons of it ends up in the oceans. Nevertheless, countries are increasingly weary of importing plastic waste. After imported plastic waste was found dumped on its beaches, Turkish authorities have followed China and banned the import plastic waste. 'We'll likely move this problem to another country again' warns Navarre.

Surprisingly little plastic from vegetables, much more from soft drinks

Navarre considered where plastic goes, but also where it comes from. He investigated Dutch food packaging because it makes up over 50% of Dutch plastic waste and detailed estimates of plastic use across the entire Dutch diet had not been attempted yet. Navarre found that in the Netherlands we use 2.1 kilos of plastic for every hundred kilos of food. 'That is certainly not all bad, plastic has many advantages like reducing food waste. For example, fruits and vegetables stay fresh longer.' Although it is precisely this packaging that has a bad image among consumers, Navarre finds that its share in the waste mountain is surprisingly small. The biggest chunk of waste comes from soft drink packaging. 'What we've contributed with our work, is a clear understanding of where the waste comes from. This knowledge should help us find better solutions to our plastic problem and prevent the waste from even existing in the first place.'

Navarre adds that proper recycling remains an important solution, 'but we need to address the problem from different angles as well' says Navarre. 'We'll need more transparent government policies and innovations to reduce how much plastic we use in the first place.'

Text: Rianne Lindhout

Photo: Plastic waste in Turkey © Caner Ozkan, Greenpeace