Morgan Botrel and Roxane Maranger

Credit: Félix Hilt

Canada has more lakes than any country in the world - more than 900,000 - and its population depends on them for drinking water, water to irrigate crops, and water in which to fish, swim, and boat on.

But Canadian lakes and their watersheds are under pressure: with the climate changing, farming intensifying, and cities and industry expanding, pollutants are increasingly infiltrating aquatic habitats, threatening the health of lakes and the ecosystem services they provide.

Which lakes are being used? What conditions are they in, are they under threat and if so, from what human activities? To answer these questions, a team of biologists at Université de Montréal combined three national datasets to come up with a first-ever "social-ecological" map of the overall health of Canadian lakes.

Their study, which looked at 659 lakes in 12 southern Canadian ecozones, is published in the journal Facets.

Led by professor Roxane Maranger with then-members from her lab - Andréanne Dupont, Morgan Botrel and Nicolas St Gelais - the scientists analyzed information collected from three independent national datasets: the NSERC Canadian Lake Pulse Network (2019), the World Wildlife Fund Canada'a Watershed Reports (2017) and Statistics Canada's Survey on the Importance of Nature to Canadians (1996).

The first set, in which first student author Dupont participated as part of a national collaborative effort, provided data on the biophysical and chemical characteristics of lakes. The second evaluated the level of threats to the lakes' health, and the third established what recreational uses Canadians were making of their lakes, corrected for current population densities.

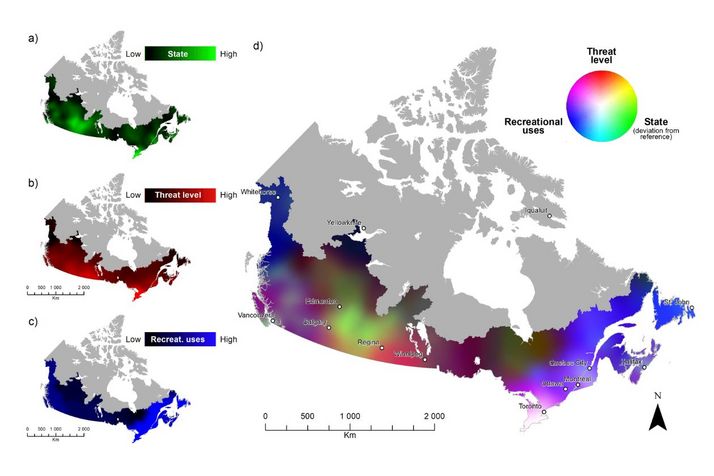

Using a colour-coded mapping technique, the scientists were able to identify regions where lakes were altered, threatened, and used: primarily around dense urban areas of southern Ontario and Quebec, and major cities on the East and West coasts. Lakes in the Prairie Provinces were altered and threatened, but seemingly less used, the researchers found.

Threats include pollution, climate change, invasive species, overuse of water, and loss of natural habitat. The highest overall threat levels were found around the Great Lakes and the southern part of the Prairies. Regions within the St. Lawrence River watershed were the only ones affected by water overuse in the assessment used. Pollution was a widespread threat, especially along the U.S. border.

When lakes with impacted watersheds were compared to healthy ones within their region, two early warning signals of human pressure emerged: nitrogen pollution from agricultural fertilizers and sewage, and chloride from road salt. Combined with information on threats and recreational use, a portrait emerged of the lakes' altered states.

On the composite map the UdeM researchers developed, colours get lighter the more a region's lakes are problematic:

- The dominant colour in eastern Canada changes from purple in the northern regions to magenta in the south, reflecting high use of the lakes there (given the colour blue) through recreational activities like power-boating.

- In Quebec (in the Lower St. Lawrence watershed between Montreal and Quebec City) and in Nova Scotia (around Halifax), colours tend to light cyan, indicating high recreational use combined with an altered ecology and a moderate level of threats.

- The tip of highly populated southern Ontario, home to 20 per cent of Canada's population, appears in white, indicating that lakes there are "altered, threatened and intensively used," according to the study.

- In Western Canada, similar colour gradients as in the East emerged - around Vancouver and Victoria, most notably, and Saskatoon and Edmonton - but shades tended to be darker, suggesting the threats of agriculture and urbanization outweighed low recreational use.

- In southern Manitoba, colours vary from orange to red, suggesting that despite the strong presence of threats, lakes sampled there have suffered minimal alteration. In southern Saskatchewan, however, the dominant colour is yellow, indicating significant levels of threat and alteration.

- In northern Canada (Quebec, Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta and the Northwest Territories) the main colour is dark brown, indicating "a low level of threat, little to no recreational use, and low levels of lake alteration," the study concludes.

"This work is novel for many reasons," said Maranger, who holds a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in aquatic ecosystem science and sustainability.

"First, our study respects that the healthy state of a lake varies across different regions in Canada. This is important as understanding whether a lake is altered or not, needs to be placed in its regional context," she said.

"Second, it shows that increasing nitrogen and chloride concentrations are clear indicators of human activities. Nitrogen pollution, from agricultural fertilizer run off and sewage, contributes to nutrient over-enrichment of lakes and the formation of harmful algal blooms, while chloride from road salt reduces the potability of water and the affects organisms that can reside in the lake.

"Third, ours is the first study of its kind that combines social information - the recreational use of lakes - with the ecological state of lakes and their future threats, thus providing a quantitative global portrait of the health of Canada's lakes on a national scale."

The approach she and her colleagues in UdeM's Department of Biological Sciences have taken with their new study should have benefits beyond simply the scientific community, Maranger added.

"What we've produced is very adaptable, easy to understand, and could be used by stakeholders and managers at the regional and local levels to determine priority sites for conservation and restoration," she said.

"And with it, they can also more effectively communicate the state of overall lake health in their areas to the people who live there - and encourage them to change how they go about putting the lakes to use."

About this study

"A social-ecological geography of southern Canadian Lakes," by Andréanne Dupont et al, was published Nov. 16, 2023 in Facets.