Male mastodons, extinct relatives of elephants that lived in North America more than 13,000 years ago, roamed hundreds of miles each year to find love.

The discovery, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is among the first studies of its kind to examine the annual migration patterns of the biggest extinct animals from the Pleistocene Epoch.

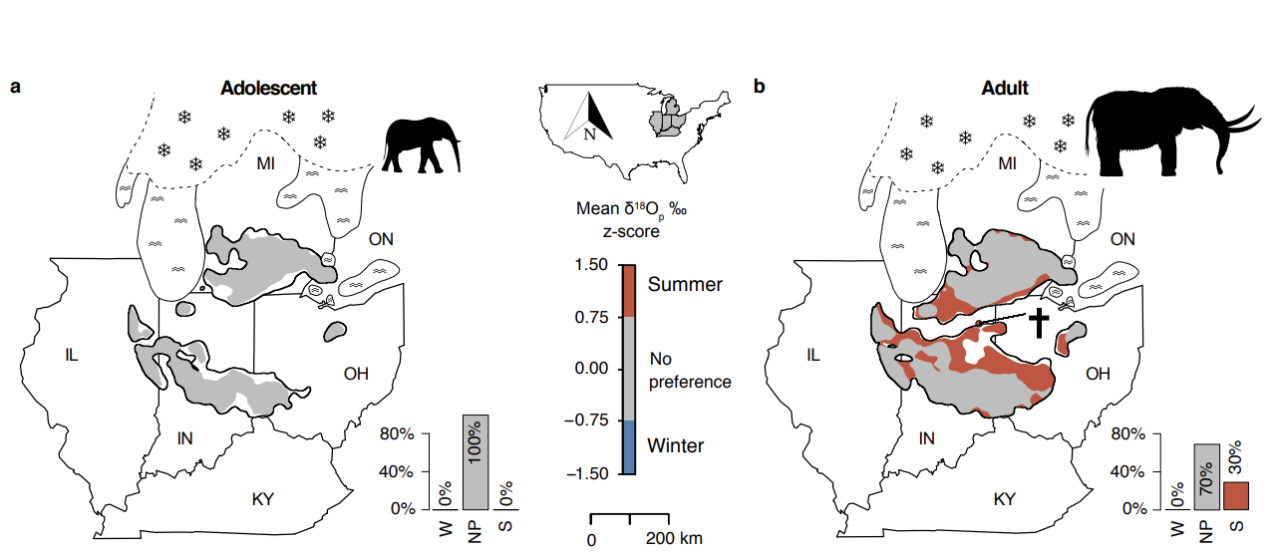

Using isotopic analysis of the tusk of a male mastodon discovered on a peat farm in Fort Wayne, Indiana, researchers were able to track changes in landscape use between his teenage and adult years. During the mastodon's early adolescence, he stuck to an area that included central Indiana and southwestern Ohio. After being kicked out of his maternal herd, his home range began to increase.

Researchers conducted an isotopic analysis on the tusks of a 13,000-year-old fossilized mastodon, on display at the University of Michigan, to track its seasonal migration over its lifetime. Photo/Eric Bronson/Michigan Photography

This behavior of male mastodons staying with the natal herd until adolescence and then striking out on their own is similar to that of male African elephants. The two species are separated by 24 million years of evolution. Previous studies of mastodon tusks have found evidence of nutritional stress in adolescents during the time they leave their natal herds, but this study is the first to document their subsequent nomadic lifestyles that came with growing up.

As an adult, the mastodon traveled an even larger territory, including repeated summer migrations to a mating ground in northeast Indiana. It was in this area, nearly 100 miles from his core range, where he died.

Researchers say the hulking animal, which boasts 9-foot tusks, was around 34 years old when it was impaled by the tusk of another male mastodon, probably during a dominance fight over access to females.

"In elephants, breeding males can experience a hormonally charged period called musth when they can become especially aggressive," said Joshua Miller, the study's first author and an assistant professor of geology in UC's College of Arts and Sciences.

"Males can get into brutal fights and even kill each other," Miller said. "There are many indications that mastodon males also experienced musth."

UC assistant professor of geology Joshua Miller examines a fossilized mastodon at the Cincinnati Museum Center. Miller found tooth marks on the skeleton's scapula suggesting a predator such as a dire wolf fed on the mastodon. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

The mastodon specimen, on display at the Indiana State Museum, is nicknamed Fred after Fred Buesching, owner of the Indiana peat farm where Buesching's grandson discovered the fossils in 1998.

Miller said he is curious how mastodons lived alongside other Pleistocene megafauna, particularly the far bigger woolly mammoths that also wandered North America. While mastodons were believed to eat leaves and twigs, mammoths were mostly grazers like today's African elephants.

"We'd love to understand more about how they coexisted. One possibility is that differences in how they used landscapes were important for minimizing negative interactions," Miller said. "Did they share the same mating areas? Or was it too dangerous to have both mastodons and mammoths in musth at the same time and place?"

To learn about the travels of Fred the mastodon, researchers examined his tusks - modified teeth that grow throughout life. They took multiple tusk samples from Fred's adolescence and adulthood to track the mastodon's seasonal movements.

In particular, the team studied strontium and oxygen isotopes in the tusks. Strontium is one of the most common elements on Earth. But the ratio of two of its isotopes varies across space, largely depending on the composition of local geology. Likewise, studying changes in oxygen isotopes throughout the tusk can identify the season (for example, summer or winter) during which different portions of tusk were grown.

Together, the two isotopes can be used to turn different tusk layers into what amounts to a GPS track that records where he was during different seasons.

"This is the first time it's been clearly shown that mastodons had a regular, annual pattern of migration and that it was connected with mating behavior," said Daniel Fisher, co-lead author of the study and a paleontologist with the University of Michigan.

Using isotopic analysis from a tusk, researchers were able to track the seasonal movements of the mastodon across what is now Ohio, Indiana, Michigan and Illinois. Researchers believe mastodons might have traveled hundreds of miles to find mates.

Study co-author Brooke Crowley, UC professor of geology and anthropology, has used isotopic analysis to learn the habitat needs of rare, elusive wildlife such as jaguars, far-ranging animals such as caribou and birds of prey and extinct animals such as mammoths and mastodons.

UC assistant professor Joshua Miller worked with a team of researchers that revealed the seasonal movements of an Ice Age mastodon that died more than 13,000 years ago. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

"While the American mastodon was the first vertebrate fossil species to be recognized in North America, nearly 300 years ago, this impressive study shows how new aspects of an extinct animal's paleobiology can still be uncovered through the use of innovative methods," said Glenn Storrs, curator of vertebrate paleontology for the Cincinnati Museum Center, which also has a fossilized mastodon on display.

"[Miller] and his colleagues have brought to bear new analytical tools that allow remarkable insight into the social and mating behaviors, as well as the potential migration patterns, of a long dead resident of the Midwest," Storrs said. "It's exciting to think that, as demonstrated in this research, this particular mastodon may even have visited Cincinnati over 10,000 years ago."

Researchers said similar tools could be used to study how the historic movements of elephants or other species have changed over centuries in the face of human development.

"This geochemical tool is a really powerful method for better understanding the behavior of still-living animals," UC's Crowley said. "It isn't possible to observe everything an individual animal does. Animals today may behave in ways that differ from what they would do if they lived in environments that weren't filled with alien plants, introduced animals that compete for food or in landscapes dissected by roads, farms and cities."

The study was a collaboration among the University of Cincinnati, the University of Michigan and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. The project was supported by the National Science Foundation, the UC Office of Research, the University of Michigan and the Minihaha Foundation of Leo, Indiana.

Featured image at top: UC research collaborators Brooke Crowley, Joshua Miller and Bledar Konomi used an isotopic analysis to track the seasonal movements of an extinct mastodon during the Ice Age more than 13,000 years ago. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing & Brand

Bledar Konomi, left, associate professor of mathematical sciences, Brooke Crowley, associate professor of geology and anthropology, and Joshua Miller, assistant professor of geology, collaborated on a study examining the seasonal migration of Ice Age megafauna. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand