A team of scientists including the University of Toronto's Bart Ripperda and Braden Gail - assistant professor and graduate student, respectively, at the Canadian Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics in the Faculty of Arts & Science - have made the first-ever detection of a mid-infrared (mid-IR) flare from the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way Galaxy.

Known as Sgr A* - pronounced "Sagittarius A star" - the supermassive black hole is four million times the mass of the sun and is known to exhibit flares that can be observed in multiple wavelengths, allowing scientists to see different views of the same flare and understand the mechanisms and timelines behind flare emissions.

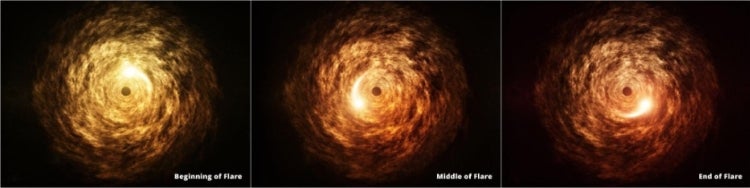

However, mid-infrared observations had eluded scientists for decades - until April 6, 2024, when scientists using the James Webb Space Telescope detected a flare lasting about 40 minutes.

The observation , which will be outlined in Astrophysical Journal Letters, could help fill a gap in scientists' understanding of what causes flares and address questions about whether their theoretical models are complete.

"The flare observed at the centre of the Milky Way Galaxy with JWST was so well-monitored that we are not just able to infer the properties of the radiation, but we can learn something about the electrons that orbit the black hole and emit the photons," Ripperda said. "The data is so rich that we could really test our theories of how these flares work via simulations."

Infrared light is a type of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths longer than visible light, but shorter than radio waves. The mid-IR part of the electromagnetic spectrum allows astronomers to observe objects like flares that are often difficult to observe in other wavelengths due to impenetrable dust.

Scientists aren't 100 per cent certain as to why flares occur, so they rely on models and simulations that they compare with observations to try to understand what causes them. Many simulations suggest the flares in Sgr A* are caused by the interaction of magnetic field lines in its turbulent accretion disk.

When two magnetic field lines approach each other, they can connect to each other and release a large amount of their energy. A byproduct of this magnetic reconnection is synchrotron radiation emitted by moving electrons. The emission seen in the flare intensifies as energized electrons travel along the supermassive black hole's magnetic field lines at close to the speed of light.

Gail, who ran simulations on a Canadian supercomputer, said this line of research enables scientists to "prove the fundamental physics of how supermassive black holes accrete material" - a process that's known to reshape and evolve galaxies. "The recent mid-infrared observation, in addition to existing near-infrared, X-ray and radio, are all critical pieces in solving this puzzle," Gail said. "Discovering the change in spectral index is particularly important in understanding how emitted energy from these flares evolve over time, helping us better understand and model the processes related to their creation and evolution."

Joseph Michail, one of the lead authors of the new paper and a post-doctoral fellow at the Center for Astrophysics, Harvard & Smithsonian, added Sgr A*'s flares evolve rapidly, and that not all the changes can be detected at every wavelength. "For over 20 years, we've known what happens in the radio and near-infrared ranges, but the connection between them was never 100 per cent clear," Michail said. "This new observation in mid-IR fills in that gap."