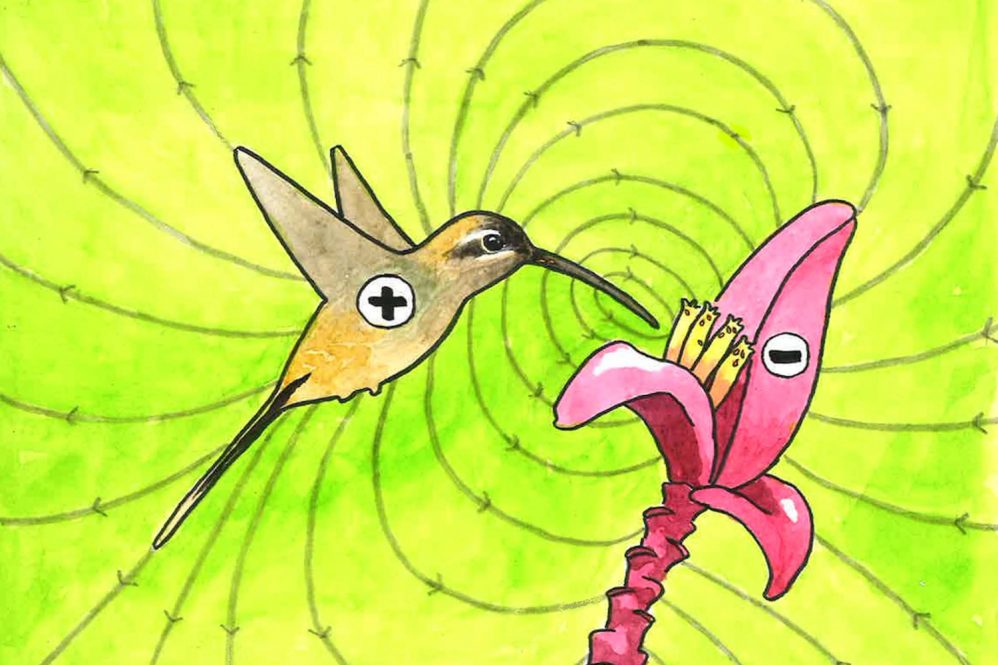

A fascinating example of how some creatures sense and rely on electric fields for survival

(Illustration courtesy of Marley Peifer)

Mites who hitchhike on the beaks of hummingbirds use a surprising method to help them on their journey: electricity.

These hummingbird flower mites feed on nectar and live within specific flowers for their species. When it is time to seek out a new flower, they hitch a ride via hummingbirds, but for years researchers have not been sure exactly how these tiny, crawling arachnids quickly disembark at the right flower. Researchers, including Carlos Garcia-Robledo, associate professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, are closer to answering these questions, and they published their results in PNAS.

Garcia-Robledo studies aspects of the evolutionary and life histories of organisms and how they respond to climate change, including this puzzling behavior.

"When hummingbirds visit multiple flowers, you usually see the mites going down their beaks only when they touch the first flower," says Garcia-Robledo. "I thought that was interesting and wondered why the mites were not going to the second or third flower."

For years, researchers have proposed that the mites use a smell signal, but after some experimentation to test this theory, Garcia-Robledo was not convinced.

"I knew that it was not maybe the smell that played a major role in this because if you bring the mites to a laboratory, they don't care much about smells of flowers and so on. I knew it had to be something else."

Then, after reading a story about research into how ticks are pulled onto clothing by static electricity, and a chance lunch meeting while working at the La Selva Research Station in Costa Rica, everything came together.

"I was reminded of the weird observation about the mites, and I thought maybe something electrostatic was happening there," he says. "These mites are so tiny that they live at another level of perception, so of course, even little electric fields are important for them. This could help explain the mystery of how they can be fast enough to hitchhike on this family of birds."

Just by chance, Garcia-Robledo was having lunch with friends and co-authors Konstantine Manser and Diego Dierick. Manser was at the time a Ph.D. student at the University of Bristol in the laboratory that produced the tick static research. Diego Dierick is a scientist at the Organization for Tropical Studies, and an electronics whiz collaborating in many projects at La Selva Research Station. Garcia-Robledo proposed they test his theory on the hitchhiking hummingbird flower mites.

"Diego and Kosta said that it was super easy and that we should try. We built the devices the next day and brought the first mite from a flower to test it. We turned on the device, and instantaneously, they started to respond. That's how we figured out that they were using static electricity," says Garcia-Robledo.

With that immediate success, the researchers were inspired to experiment further with a power source that only generated static electricity and test whether the mites were attracted to statics or the frequency that it was transmitting. They discovered that when the field was only static electricity, the mites did not respond, yet they did when the field was modulated.

"The mites respond to the bouncing of a signal that is associated with the size, geometry, and vibration of the hummingbirds, which reach frequencies between 20 and 160 Hz," Garcia-Robledo says.

As the hummingbirds beat their wings, they generate a charge, and their bodies become supercharged. So, just like how you may get a small static shock after walking across a room and touching a door handle, the first flower seems to be the one where mites have the electric potential to embark or disembark quickly.

In another experiment, Garcia-Robledo tested how the mites recognize very small positive electrical charges. He experimented with a very simple and effective device composed of a glass tube, and wire where the wire would be touched by either an aluminum or copper plate to generate a charge. The glass tube held the mite, and when the device was charged, the mites responded by running toward the positive pole at both higher and lower electrical fields, but only when it was transmitting a frequency of 120 Hz.

"You just charge the little arena, and then instantaneously, the mite is attracted only if you have this little bounce of the signal, and they go to the positive charge even if you have these super tiny charges. The little bounce the second that you touch, it is enough for them to know where to go, and they just go," says Garcia-Robledo.

Each of the 19 mite species at La Selva is attracted to specific set of flowers, and they somehow know when they have arrived at the right flower and that it's time to jump on or hop off their hummingbird shuttle.

"We think that there may be some specificity in the electric signals or different charges for flowers," says Garcia-Robledo. "That's one possibility. We found that there is a structure in the front legs that they used to perceive these electric charges and frequencies. The next step is that we have many of these mites, and they have different structures, and different species of mites have different structures in their legs. Potentially, they can detect different frequencies."

Besides signaling when to get off, these electric charges help the mites quickly board their speedy chaperones. Just like the study looking at how ticks hitch a statically charged ride onto clothing, the mites are pulled up from the flower to the hummingbird beaks via the bird's positive charge.

"When the mites are attracted by that electric field, we found they are one of the fastest terrestrial organisms for a few milliseconds," Garcia-Robledo says. "This is the most surprising thing because the mites were not just responding to electrostatics, they are responding to an actual signal generated by an organism. That was super surprising. This may be the first kind of like case where these organisms are using, at the same time, electricity to locate organisms that they are using for transportation, but also for transportation itself."

Funding was provided by the National Science Foundation, Dimensions of Biodiversity – 1737778 and Organismal Responses to Climate change – 2222328.