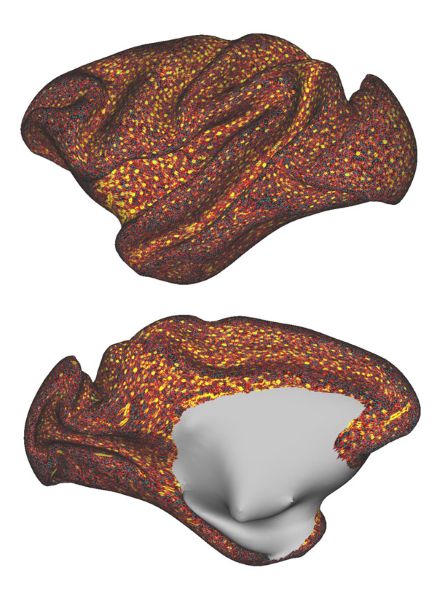

Figure 1: A high-resolution image showing the distribution of blood vessels in the macaque brain. Yellow circles indicate the sizes of vessels and cyan dots show the centers of vessels. © Reproduced from Ref. 1 and licensed under CC BY 4.0. © 2024 J. A Autio et al.

In the brain, not all blood flow is created equal. RIKEN researchers have developed a detailed cortical layer map of the blood vessels that weave through the brain of macaque monkeys. It reveals how blood supply is finely tuned to fuel critical functions such as perception and cognition1.

The network of blood vessels in the brain supplies the various brain regions with oxygen and nutrients. Determining the relationship between the brain's vascular network and its energy demands is important for understanding how the brain's inner workings might create vulnerabilities to stroke, Alzheimer's and other neurological diseases.

However, there is still much we don't understand about the architecture of the vascular network in the brain.

Now, Joonas Autio of the RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research and co-workers have mapped blood volume across cortical layers and the entire cortex of macaque monkeys by using high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging.

Their measurements revealed that the distribution of blood vessels is far from uniform, and that these variations align with neuroanatomical differences. The vasculature scales positively with neuron density, whereas layers and regions with higher synaptic densities exhibit relatively sparser vascularization.

In particular, blood vessels are concentrated in regions essential for sensory processing, particularly vision. In contrast, they are sparser in areas responsible for higher cognitive functions, such as abstract thinking and decision making.

This uneven distribution in the macaque brain probably reflects the prioritizing of more pressing, survival-driven tasks managed by the visual cortex and other regions processing external stimuli over more cognitive functions.

"Evolutionary pressures may have optimized the vascular architecture to support the high metabolic demands of visual processing," says Autio. "This was likely driven by the need for efficient foraging and competition in visually dominant environments."

These methodological developments could have clinical implications. A better understanding of how blood flow is distributed across different brain regions and layers could help unravel how vascular dysfunction impacts disorders linked to neurodegeneration and aging. The ability to map feeding arteries and draining veins with such precision also offers hope for developing targeted therapies for neurological conditions, Autio says.

The findings raise intriguing questions about human brains. While similar cortical layer vascular maps don't yet exist for people, Autio suspects that our brains might have denser vascular networks in regions associated with working memory and higher order functions, as humans tend to engage in more complex and sustained cognitive tasks than monkeys.

"This could provide a framework for understanding differences in brain function and energy needs across species," he says.

Joonas Autio (orange shirt in right back row) and his team have mapped blood vessel patterns in the primate brain, revealing how evolution optimized blood flow to fuel energy-intensive regions like the visual cortex. © 2025 RIKEN