The mechanisms we use to sense quantity are located in our pupils. This is the result of a study conducted by the School of Psychology of the University of Sydney, in collaboration with the Universities of Pisa and Florence (Italy), recently published in Nature Communications.

"When we look around, we spontaneously perceive the form, size, movement and colour of a scene. Equally spontaneously, we perceive the number of items before us. This ability, shared with most other animals, is an evolutionary fundamental: it reveals immediately important quantities, such as how many apples there are on the tree, or how many enemies are attacking," said co-author, Professor David Burr from the Universities of Sydney and Florence.

Information about numbers is so important that it is thought most species have a dedicated 'number sense', Professor Burr, from the School of Psychology said.

Given the importance of the spontaneous perception of quantity, the scientists asked if it may be revealed by a primitive, automatic physiological response.

The pupil light reflex is probably the most automatic physiological response: it constricts in light and dilates in darkness. "Recent research from our laboratory shows that pupil size is also regulated by cognitive and perceptual factors," said senior author Professor Paola Binda from the University of Pisa.

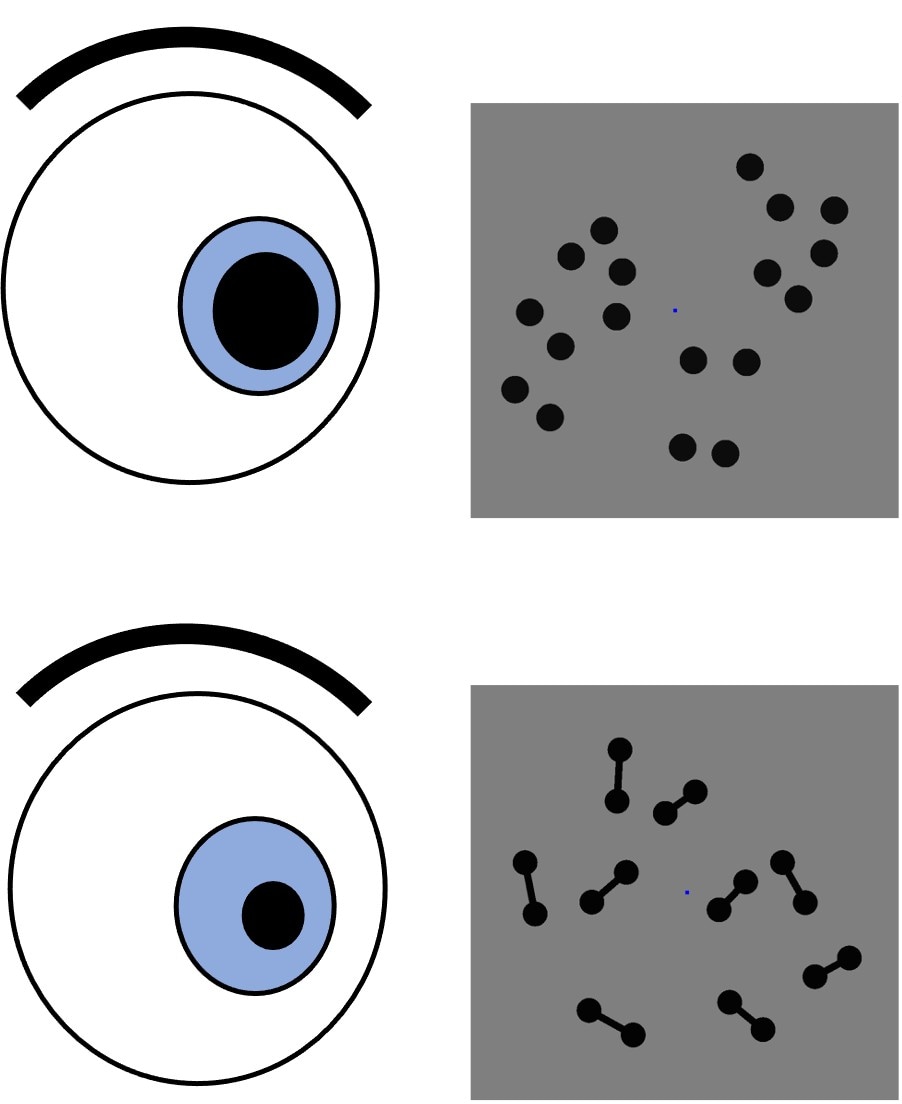

Figure 1.

The present study took advantage of this discovery. To a group of adult participants, the researchers presented images with a variable number of dots (18 or 24), which were either isolated, or connected by lines (see Fig1). Connecting the dots into dumbbell shapes causes the dots to appear fewer (although they are the same number), a well-known illusion. The participants observed the patterns passively, without paying special attention to the number of objects in them, or any other attribute.

Even though the number of pixels (black or white) were the same for all patterns, the diameter of participants' pupils varied according to the perceived number of dots; they were greatest when the perceived number was high, and least when it was low.

"This result shows that numerical information is intrinsically related to perception," said Dr Elisa Castaldi from Florence University. "This could have important, practical implications. For example, this ability is compromised in dyscalculia which is a dysfunction in mathematical learning, so our experiment may be useful in early identification of this condition in very young children. It is very simple: subjects simply look at a screen without making any active response, and their pupillary response is measured remotely."

The researchers intermittently worked from pubs due to COVID restrictions. L-R: Antonella Pomè, Paola Binda and David Burr working at the Orzo Bruno (Brown Barley) pub in Pisa.

The research results from a network of excellence between the Universities of Sydney, Pisa and Florence, and the National Research Council of Pisa. It was financed by two European Research Council grants, a Marie Curie Fellowship, and an ARC Discovery Grant.