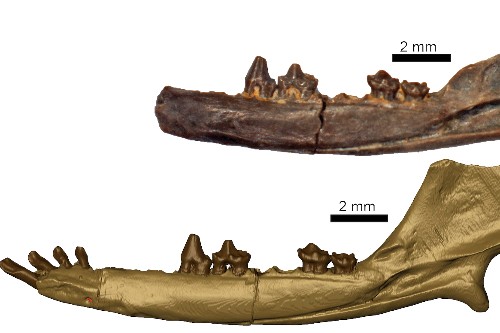

The jaw of the early mammal Morganucodon, showing the original fossil (top) and a 3D model with information from other specimens Dr Pam Gill

Kenneth Kermack (1919-2000), drawing from about 1980 Drawing by Tony Lee (UCL)

Francis Rex Parrington (1905-1981), shown in the 1960s Image discovered by German palaeontologist Walter G Kühne at Holwell, Somerset

The hunt for the world's most ancient mammals descended into academic warfare in the seventies, researchers from the University of Bristol have discovered.

In a study published today in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, Professor Mike Benton University of Bristol's School of Earth Sciences and Dr David Whiteside and Dr Pam Gill also of the School of Earth Sciences and Scientific Associates of the Natural History Museum suggest Professors from Cambridge and London Universities accused each other of bad behaviour as a dispute broke out over fossil rights.

Professor Rex Parrington from Cambridge University and Professor Kenneth Kermack from University College, London (UCL) were studying the world's oldest mammals, from the Triassic and Jurassic of south Wales, from rocks in caves and fissures about 200 million years old. However relations soured after Professor Parrington's team seemingly took four tons of clay rich in fossils that Professor Kermack had collected from quarries in South Wales.

The fossils were tiny teeth, jaws, and other bones from shrew-sized little animals that were the distant ancestors of humans, cats, and dogs. These fossils were hugely important for understanding how mammals originated, and especially the timing of all their special features such as warm-bloodedness, large brains, specialized teeth, parental care and milk.

"We spoke to Cambridge students of the time," said Professor Benton, lead author of the paper. "They reported that this pile of sediment was their main work for a long time. The students processed the clay in different chemicals to break it down and picked out teeth and jaw bones under the microscope. They got some excellent specimens, which Parrington was able to study.

"Kermack was furious and made his views clear that Parrington had stolen his rocks.

"Parrington meanwhile said that the pile of mud had been left to rot and should be available for study and he had done the right thing in sharing it with his students."

Dr Whiteside explained: "We spoke to other students from Cambridge and UCL at the time, and they helped us to piece together what had happened and why the dispute rumbled on.

"It seems that Kermack had been collecting his specimens from quarries in south Wales, and he used to bring back tons of sediment to be processed and the tiny teeth were picked out.

"He had apparently left a pile of four tons of clay with fossils at one of the quarries, and Parrington's team came down with a truck in 1966 and took most of it back to Cambridge."

"I was a PhD student with Professor Kermack in the 1970s," said Pam Gill. "I knew that relations were strained between my supervisor and Professor Parrington, but, by working on the fossil mammals in both their collections, I rather naïvely got caught in the cross-fire.

"This all matters because these locations in south Wales were nearly the only source of such ancient mammal fossils anywhere in the world, and palaeontologists around the world were waiting for the latest reports from Kermack or Parrington to understand these rather limited but rare clues about the earliest mammals.

"Now we have amazing fossils from China, Brazil, and other parts of the world, and it's hard to realise just how important those British fossils were at that time."

The first finds had been made about 1850 near Bristol and since then the fossils usually piled up very slowly. However, a German palaeontologist Walter G Kühne, a brilliant fossil finder, discovered many new fossil localities in the 1940s and 1950s and these provided the great horde of fossils which was the basis of the dispute between Kermack and Parrington.

"Digging into this history has been fascinating," concluded Professor Benton. "We had lived through the tail-end of the time of squabbles, and wanted to get the truth from both sides before it was all forgotten. We had no idea we would unearth such amazing stories, and that they are all true!"

The paper:

'Finding the world's oldest mammals: sieving, dialectical materialism, and squabbles' by Michael J. Benton, Pamela G. Gill, and David I. Whiteside in Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society (doi: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlad089).