A Cornell-led collaboration devised a new method for designing metals and alloys that can withstand extreme impacts: introducing nanometer-scale speed bumps that suppress a fundamental transition that controls how metallic materials deform.

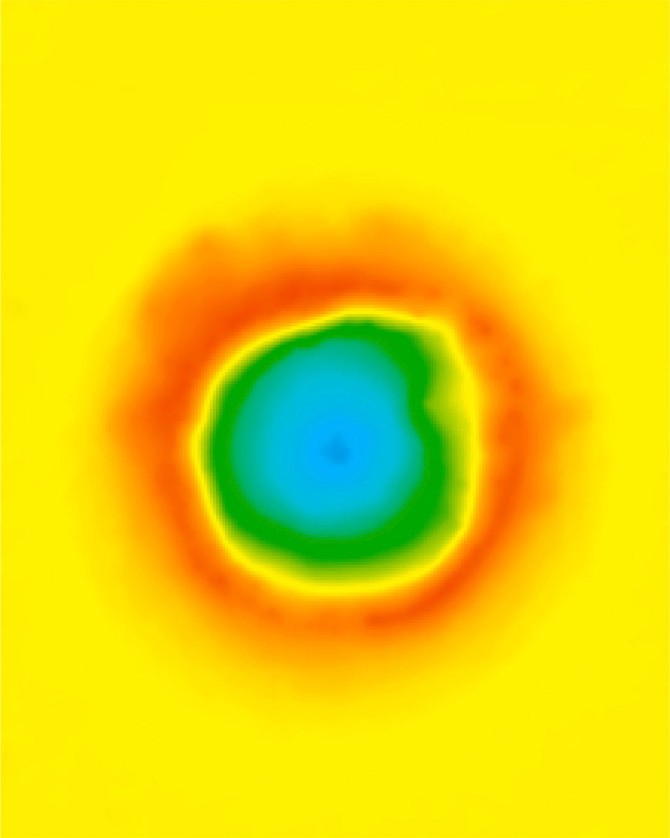

This laser confocal microscopy reconstruction shows the impression of a spherical microprojectile impact.

The findings, published March 5 in Communications Materials, could lead to the development of automobiles, aircraft and armor that can better endure high-speed impacts, extreme heat and stress.

The project was led by Mostafa Hassani, assistant professor in the Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering and in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering in Cornell Engineering, in collaboration with researchers from the Army Research Laboratory (ARL). The paper's co-lead authors were doctoral candidate Qi Tang and postdoctoral researcher Jianxiong Li.

When a metallic material is struck at an extremely high speed - think highway collisions and ballistic impacts - the material immediately ruptures and fails. The reason for that failure is embrittlement - the material loses ductility (the ability to bend without breaking) when deformed rapidly. However, embrittlement is a fickle process: If you take the same material and bend it slowly, it will deform but not break right way.

That malleable quality in metals is the result of tiny defects, or dislocations, that move through the crystalline grain until they encounter a barrier. During rapid, extreme strains, the dislocations accelerate - at speeds of kilometers per second - and begin interacting with lattice vibrations, or phonons, which create a substantial resistance. This is where a fundamental transition occurs - from a so-called thermally activated glide to a ballistic transport - leading to significant drag and, ultimately, embrittlement.

"What you really want in a metallic material is the ability to absorb energy. So one mechanism to absorb energy would be deformation or ductility. In this case, we hope that by suppressing the ballistic transport of dislocations, and, in turn, by preventing the embrittlement, we let the alloy deform, even under a very high rate of deformation, such as those that happen under impact or shock conditions," Hassani said. "To suppress ballistic dislocation transport and the resulting phonon drag, we use the concept of confining dislocations' motion, their glide, to nanometer scale."

Hassani's team worked with the ARL researchers to create a nanocrystalline alloy, copper-tantalum (Cu-3Ta). Nanocrystalline copper's grains are so small, the dislocations' movement would be inherently limited, and that movement was further confined by the inclusion of nanometer clusters of tantalum inside the grains.

To test the material, Hassani's lab used a custom-built tabletop platform that launches, via laser pulse, spherical microprojectiles that are 10 microns in size and reach speeds of up to 1 kilometer per second - faster than an airplane. The microprojectiles strike a target material, and the impact is recorded by a high-speed camera. The researchers ran the experiment with pure copper, then with copper-tantalum. They also repeated the experiment at a slower rate with a spherical tip that was gradually pushed into the substrate, indenting it.

The biggest challenge, however, was parsing the data. The key was to track the amount of energy used in each impact and indentation. Tang and Li developed a theoretical framework to separate the contributions of the two mechanisms - thermal activation at the low rate, and ballistic transport at the high rate.

"While we are measuring things at high rates - the impact and rebound velocities and particle size - how can we treat the data so that we can really isolate the contribution of dislocation-phonon drag and systematically suppress that contribution?" Hassani said.

In a conventional metal or alloy, dislocations can travel several dozen microns without any barriers. But in nanocrystalline copper-tantalum, the dislocations could barely move more than a few nanometers, which are 1,000 times smaller than a micron, before they were stopped in their tracks. Embrittlement was effectively suppressed.

"This is the first time we see a behavior like this at such a high rate. And this is just one microstructure, one composition that we have studied," Hassani said. "Can we tune the composition and microstructure to control dislocation-phonon drag? Can we predict the extent of dislocation-phonon interactions?"

Co-authors include Billy Hornbuckle, Anit Giri and Kristopher Darling with ARL.

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation and the Army Research Office.