5 min read

New findings using data from NASA's IXPE (Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer) mission offer unprecedented insight into the shape and nature of a structure important to black holes called a corona.

A corona is a shifting plasma region that is part of the flow of matter onto a black hole, about which scientists have only a theoretical understanding. The new results reveal the corona's shape for the first time, and may aid scientists' understanding of the corona's role in feeding and sustaining black holes.

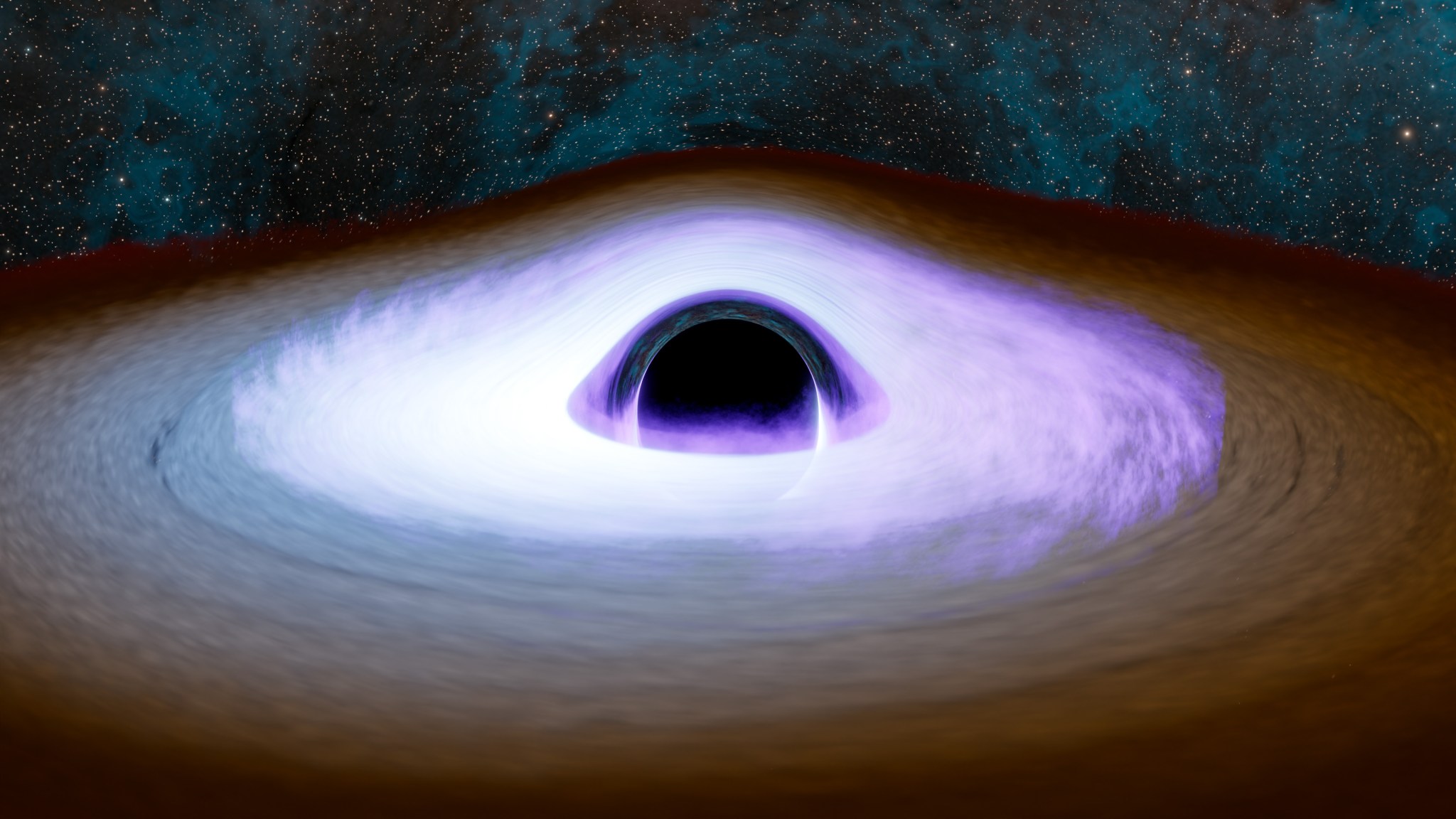

Many black holes, so named because not even light can escape their titanic gravity, are surrounded by accretion disks, debris-cluttered whirlpools of gas. Some black holes also have relativistic jets - ultra-powerful outbursts of matter hurled into space at high speed by black holes that are actively eating material in their surroundings.

Less well known, perhaps, is that snacking black holes, much like Earth's Sun and other stars, also possess a superheated corona. While the Sun's corona, which is the star's outermost atmosphere, burns at roughly 1.8 million degrees Fahrenheit, the temperature of a black hole corona is estimated at billions of degrees.

Astrophysicists previously identified coronae among stellar-mass black holes - those formed by a star's collapse - and supermassive black holes such as the one at the heart of the Milky Way galaxy.

"Scientists have long speculated on the makeup and geometry of the corona," said Lynne Saade, a postdoctoral researcher at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, and lead author of the new findings. "Is it a sphere above and below the black hole, or an atmosphere generated by the accretion disk, or perhaps plasma located at the base of the jets?"

Enter IXPE, which specializes in X-ray polarization, the characteristic of light that helps map the shape and structure of even the most powerful energy sources, illuminating their inner workings even when the objects are too small, bright, or distant to see directly. Just as we can safely observe the Sun's corona during a total solar eclipse, IXPE provides the means to clearly study the black hole's accretion geometry, or the shape and structure of its accretion disk and related structures, including the corona.

"X-ray polarization provides a new way to examine black hole accretion geometry," Saade said. "If the accretion geometry of black holes is similar regardless of mass, we expect the same to be true of their polarization properties."

IXPE demonstrated that, among all black holes for which coronal properties could be directly measured via polarization, the corona was found to be extended in the same direction as the accretion disk - providing, for the first time, clues to the corona's shape and clear evidence of its relationship to the accretion disk. The results rule out the possibility that the corona is shaped like a lamppost hovering over the disk.

The research team studied data from IXPE's observations of 12 black holes, among them Cygnus X-1 and Cygnus X-3, stellar-mass binary black hole systems about 7,000 and 37,000 light-years from Earth, respectively, and LMC X-1 and LMC X-3, stellar-mass black holes in the Large Magellanic Cloud more than 165,000 light-years away. IXPE also observed a number of supermassive black holes, including the one at the center of the Circinus galaxy, 13 million light-years from Earth, and those in galaxies NGC 1068 and NGC 4151, 47 million light-years away and nearly 62 million light-years away, respectively.

Stellar mass black holes typically have a mass roughly 10 to 30 times that of Earth's Sun, whereas supermassive black holes may have a mass that is millions to tens of billions of times larger. Despite these vast differences in scale, IXPE data suggests both types of black holes create accretion disks of similar geometry.

That's surprising, said Marshall astrophysicist Philip Kaaret, principal investigator for the IXPE mission, because the way the two types are fed is completely different.

"Stellar-mass black holes rip mass from their companion stars, whereas supermassive black holes devour everything around them," he said. "Yet the accretion mechanism functions much the same way."

That's an exciting prospect, Saade said, because it suggests that studies of stellar-mass black holes - typically much closer to Earth than their much more massive cousins - can help shed new light on properties of supermassive black holes as well.

The team next hopes to make additional examinations of both types.

Saade anticipates there's much more to glean from X-ray studies of these behemoths. "IXPE has provided the first opportunity in a long time for X-ray astronomy to reveal the underlying processes of accretion and unlock new findings about black holes," she said.

The complete findings are available in the latest issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

More about IXPE

IXPE, which continues to provide unprecedented data enabling groundbreaking discoveries about celestial objects across the universe, is a joint NASA and Italian Space Agency mission with partners and science collaborators in 12 countries. IXPE is led by Marshall. Ball Aerospace, headquartered in Broomfield, Colorado, manages spacecraft operations together with the University of Colorado's Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics in Boulder.