4 min read

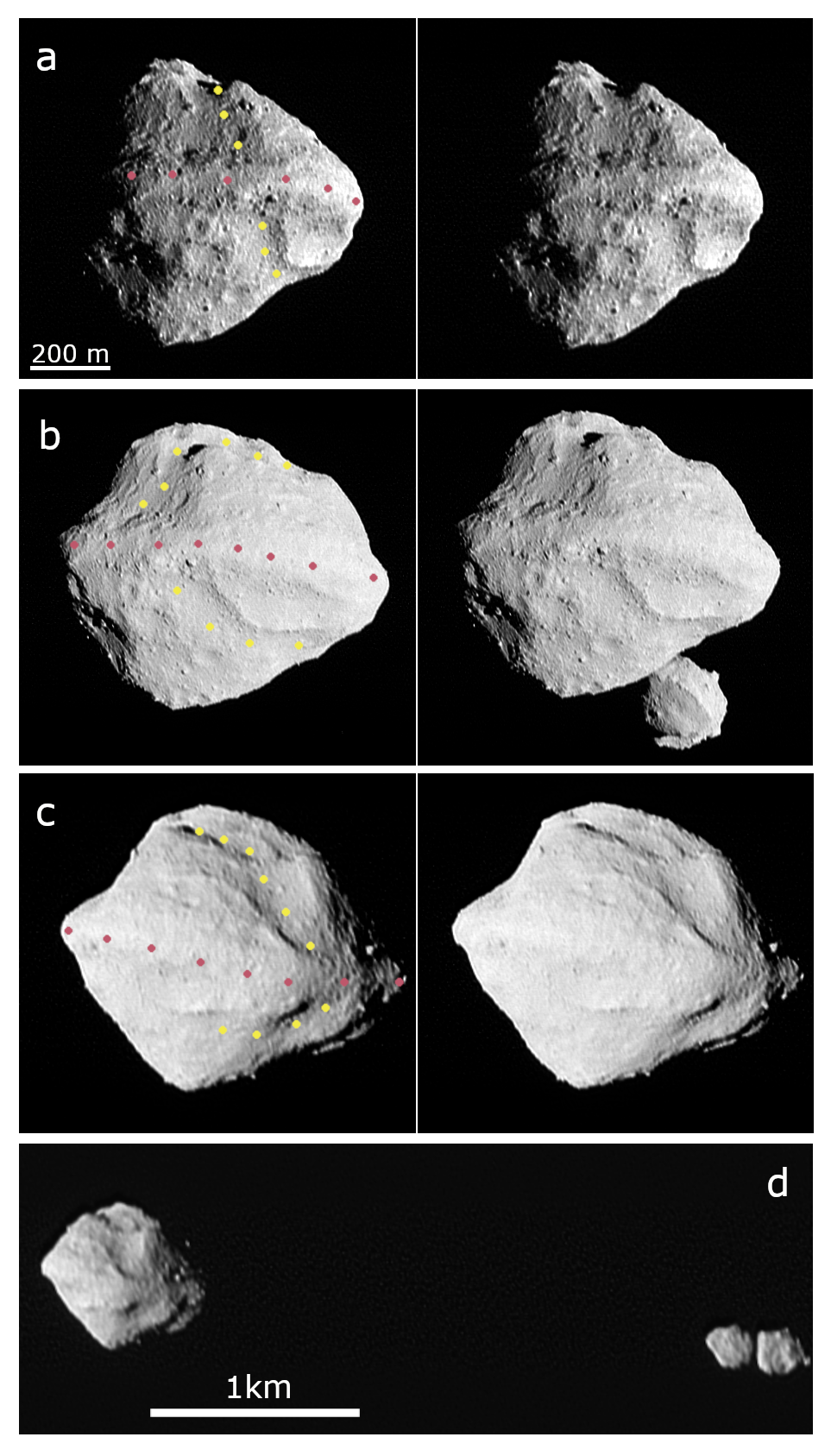

Images from the November 2023 flyby of asteroid Dinkinesh by NASA's Lucy spacecraft show a trough on Dinkinesh where a large piece - about a quarter of the asteroid - suddenly shifted, a ridge, and a separate contact binary satellite (now known as Selam). Scientists say this complicated structure shows that Dinkinesh and Selam have significant internal strength and a complex, dynamic history.

"We want to understand the strengths of small bodies in our solar system because that's critical for understanding how planets like Earth got here," said Hal Levison, Lucy principal investigator at the Boulder, Colorado, branch of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas. "Basically, the planets formed when zillions of smaller objects orbiting the Sun, like asteroids, ran into each other. How objects behave when they hit each other, whether they break apart or stick together, has a lot to do with their strength and internal structure." Levison is lead author of a paper on these observations published May 29 in Nature.

Researchers think that Dinkinesh is revealing its internal structure by how it has responded to stress. Over millions of years rotating in the sunlight, the tiny forces coming from the thermal radiation emitted from the asteroid's warm surface generated a small torque that caused Dinkinesh to gradually rotate faster, building up centrifugal stresses until part of the asteroid shifted into a more elongated shape. This event likely caused debris to enter into a close orbit, which became the raw material that produced the ridge and satellite.

If Dinkinesh were much weaker, more like a fluid pile of sand, its particles would have gradually moved toward the equator and flown off into orbit as it spun faster. However, the images suggest that it was able to hold together longer, more like a rock, with more strength than a fluid, eventually giving way under stress and fragmenting into large pieces. (Although the amount of strength needed to fragment a small asteroid like Dinkinesh is miniscule compared to most rocks on Earth.)

"The trough suggests an abrupt failure, more an earthquake with a gradual buildup of stress and then a sudden release, instead of a slow process like a sand dune forming," said Keith Noll of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, project scientist for Lucy and a co-author of the paper.

"These features tell us that Dinkinesh has some strength, and they let us do a little historical reconstruction to see how this asteroid evolved," said Levison. "It broke, things moved apart and formed a disk of material during that failure, some of which rained back onto the surface to make the ridge."

The researchers think some of the material in the disk formed the moon Selam, which is actually two objects touching each other, a configuration called a contact binary. Details of how this unusual moon formed remain mysterious.

Dinkinesh and its satellite are the first two of 11 asteroids that Lucy's team plans to explore over its 12-year journey. After skimming the inner edge of the main asteroid belt, Lucy is now heading back toward Earth for a gravity assist in December 2024. That close flyby will propel the spacecraft back through the main asteroid belt, where it will observe asteroid Donaldjohanson in 2025, and then on to the first of the encounters with the Trojan asteroids that lead and trail Jupiter in its orbit of the Sun beginning in 2027.

Lucy's principal investigator is based out of the Boulder, Colorado, branch of Southwest Research Institute, headquartered in San Antonio. NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, provides overall mission management, systems engineering, and safety and mission assurance. Lockheed Martin Space in Littleton, Colorado, built and operates the spacecraft. Lucy is the 13th mission in NASA's Discovery Program. NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, manages the Discovery Program for the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington.