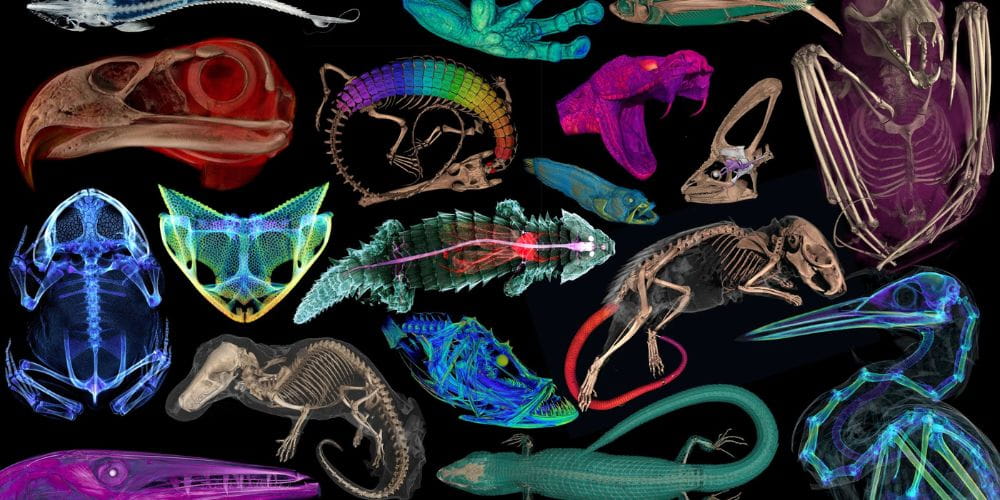

With the help of 16 grants from the National Science Foundation, researchers have painstakingly taken computed topography (CT) scans of more than 13,000 individual specimens to create 3D images of more than half of all the world's animal groups, including mammals, fishes, amphibians and reptiles.

The research team, made of members from The University of Texas at Arlington and 25 other institutions, are now a quarter of the way through inputting nearly 30,000 media files to the open-source repository MorphoSource. This will allow researchers and scholars to share findings and improve access to material critical for scientific discovery.

"Thanks to this exciting openVertebrate project, also called oVert, anyone—scientists, researchers, students, teachers, artists—can now look online to research the anatomy of just about any animal imaginable without leaving home," said Gregory Pandelis, collections manager of UT Arlington's Amphibian and Reptile Diversity Research Center. "This will help reduce wear and tear on many rare specimens while increasing access to them at the same time."

A summary of the project has just been published in the peer-reviewed journal BioScience reviewing the specimens that have been scanned to date and offering a glimpse of how the data might be used in the future.

For example, one research team has used the data to conclude that Spinosaurus, a massive dinosaur that was larger than Tyrannosaurus rex and thought to be aquatic, would have actually been a poor swimmer, and thus likely stayed on land. Another study revealed that frogs have evolved to gain and lose the ability to grow teeth more than any other animal.

The value of oVert extends beyond scientific inquiry. Artists are using the 3D models to create realistic animal replicas. Photographs of oVert specimens have been displayed as part of museum exhibits. In addition, specimens have been incorporated into virtual reality headsets that allow users to interact with the animals.

Educators also are able to use oVert models in their classrooms. From the outset of the project, the research team placed a strong emphasis on K-12 outreach, organizing workshops where teachers could learn how to use the data in their classrooms.

"As a kid who loved all things science- and nature-related and had a particular interest in skeletal anatomy, I would go through great pains to collect, preserve and study skulls and other specimens for my childhood natural history collection, the start of my scientific inspiration," Pandelis said. "Realizing that you could study these things digitally with just a few clicks on a computer was eye-opening for me, and it opened up the path to my current research using CT scans of snake specimens to study their skull evolution. Now, this wealth of data has been opened and made publicly accessible to anyone who has a professional, recreational or educational interest in anatomy and morphology. Natural history specimens have never been so accessible and impactful."

In the next phase of the research project, the team will be creating sophisticated tools to analyze the data collected. Since researchers have never had digital access to so many 3D natural history specimens before, it will take further developments in machine learning and supercomputing to use them to their full potential.

For a video snapshot of the project, watch this two-minute video.