When Letora Anderson was in graduate school, she would return home to Baton Rouge every break to visit her mother.

And each time, the now-assistant professor of landscape architecture at The University of Texas at Arlington grew disheartened as she saw her neighborhood become more run-down.

Dr. Anderson was raised in the Gus Young section of Baton Rouge, a tight-knit neighborhood named after Gustav Young, a prominent civil rights leader and one of the first Black Americans registered to vote in East Baton Rouge Parish in 1932. Seeing the tentacles of decay increasingly take over this historical area would set her on a course that would change her life.

"That experience made me ask myself, 'What mechanisms caused certain areas to decline while others didn't?'" Anderson said. "In my field now, I've been able to provide solutions for cities to help with any issues they've been dealing with through design, urban planning or community engagement."

Those trips back home inspired her to pursue a degree in landscape architecture and help revitalize struggling communities like Gus Young.

Anderson, a city planner before moving into higher education, teaches and conducts research in UTA's Landscape Architecture program in the College of Architecture, Planning and Public Affairs. Her research focuses on planning and designing neighborhoods by preserving their cultural, historical and social identities, while reconnecting residents to natural surroundings, promoting fairness in community involvement and supporting local growth.

Her dedication to enhancing communities can be seen in several Dallas neighborhoods. In South Oak Cliff, for example, she recently engaged in a partnership with the Trust For Public Land to create South Oak Cliff Renaissance Park, transforming a once-overgrown lot known for attracting criminal elements into a fully solar-powered park on 1.8 acres.

Since the park's completion, crime rates have dropped, and the outdoor space is utilized regularly by residents to safely enjoy exercise and recreation.

"This project is a perfect example of what is achievable when we return resources to the community," Anderson said.

In the classroom, she implores her aspiring landscape architects to delve into the histories of the communities they work and to reach a deep understanding of residents' needs now and in the years to come. To emphasize the lesson, she led her students to the Garden of Eden.

Located near downtown Fort Worth and Haltom City along the Trinity River, the Garden of Eden neighborhood was established by freed slaves who fled Kentucky and Tennessee around 1860. It became home to 54 families. Today, about 20 families, all descendants of the original settlers, still live there.

Much like the Gus Young neighborhood of her youth, the Garden of Eden community struggled with decline for many years due to environmental and societal disruptions such as urbanization and industrialization. Anderson tasked her students with engaging with its residents and gathering data such as how the land is being used now and how it can be utilized in the future to better serve the community.

"Going out there helps my students understand what systems have been in place that allow for a community to be dismantled," Anderson said. "And it helps residents understand where their community is now, where it's heading and how it can plan for the future.

For Anderson, her future as a landscape architect wasn't always clear. Early on, she struggled to find her footing. She said he often felt alone in a field with few other Black professionals, even experiencing imposter syndrome, a phenomenon where the person persistently doubts their accomplishments and feels like a fraud. According to the American Society of Landscape Architects, barely 2% of landscape architects are Black.

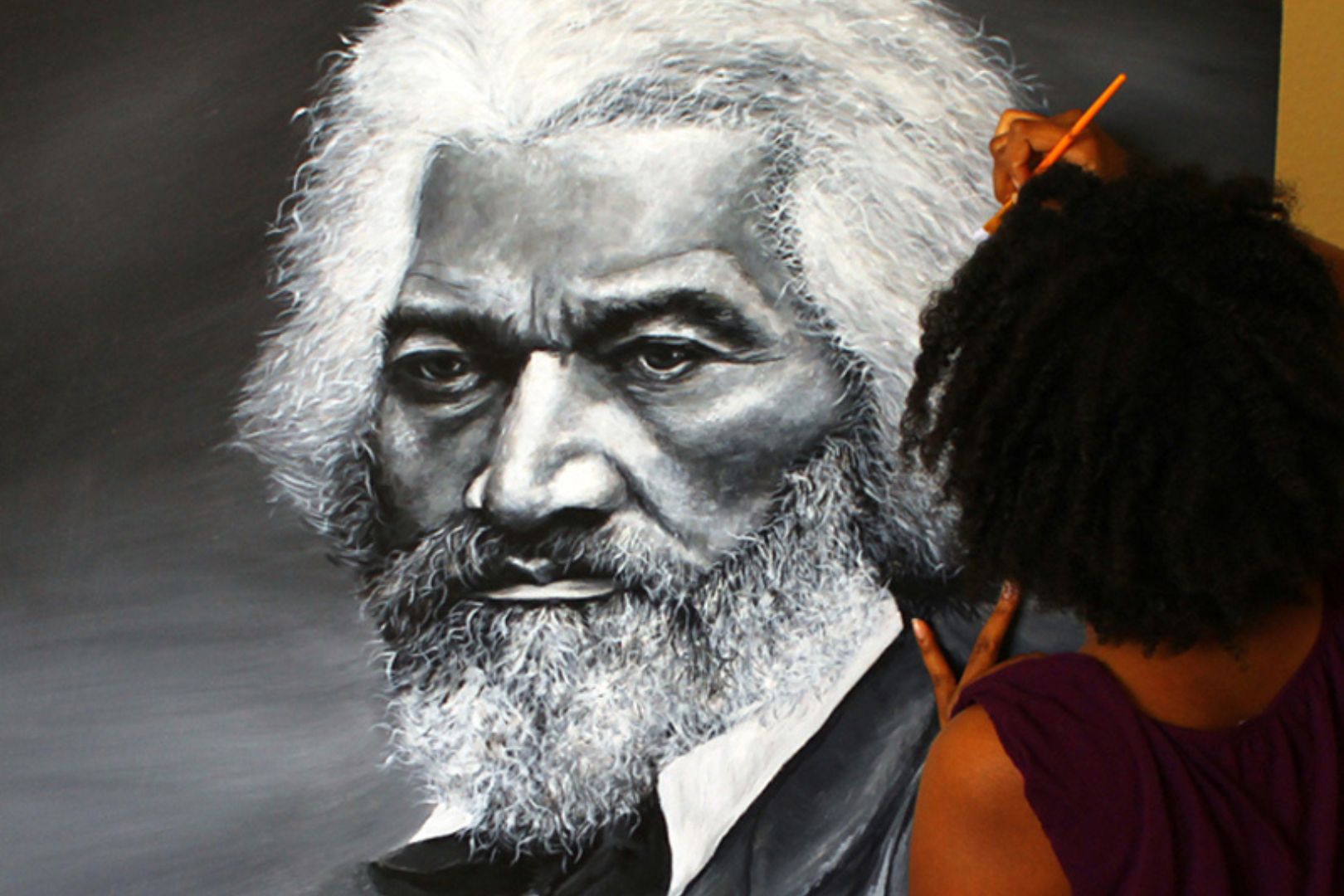

During a difficult period, Anderson, who is also an accomplished artist, sought inspiration and motivation by putting brush to canvas. She started painting portraits of prominent Black Americans like Frederick Douglass, George Washington Carver and Martin Luther King Jr.

"I wanted to focus on people who inspired me: Black Americans who made history and paved the way for me to be in the position I am in now," Anderson said. "Painting them helped me believe in myself during a low time."

As Anderson continues to mentor the next generation of landscape architects at UTA, she hopes to instill in her students the knowledge and compassion that will pave their way to revive commumnites and improve people's lives.

"I try to make them understand that each community is unique—they all have histories and issues," Anderson said. "Students have to contextualize that and make a space that works and honors those residents. I also want them to make the most out of their careers—I want them to find their passion and run with it."