(Photo illustration by Emily Faith Morgan, University Communications)

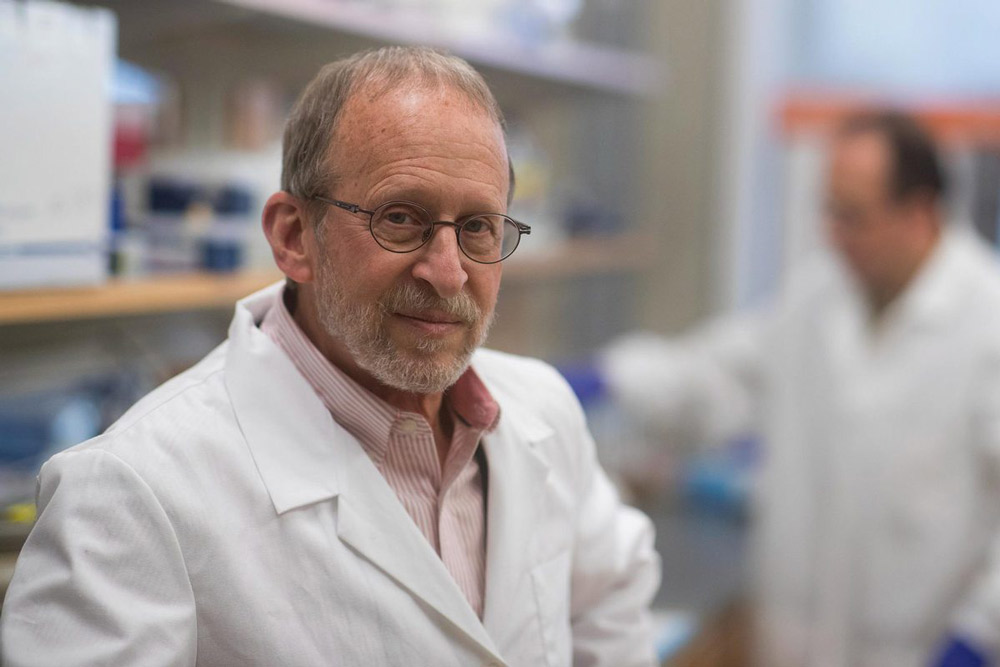

University of Virginia biology professor George Bloom is receiving revived interest lately in an old paper. Eleven years ago, he was part of a research team that illuminated the Alzheimer's brain target that a new and exciting - but not yet approved - drug called Donanemab now acts upon.

Compared to placebo, Donanemab slowed the clinical decline of Alzheimer's by 35% and resulted in 40% less decline in "the ability to perform activities of daily living," according to a press announcement.

What's more, nearly half of the experimental group was reported to have had no clinical decline after a year.

George Bloom is a biologist and UVA Health researcher who has studied the target Donanemab acts upon. (UVA Health photo)

The drug has raised hope for individuals and families who have loved ones in early stages of the disease or who are at risk for Alzheimer's. Optimism pushed Ely Lilly and Co. stock to an all-time high.

To Bloom, the target seems right. And he is rooting for the drug in whatever ways it can help people. But, he said, "Alzheimer's defects at the cellular and molecular levels start appearing 20 years before the symptoms of the disease are obvious. By then, you have massive brain damage."

A drug administered at that stage, Bloom said, is like "going deer hunting, and you pull the trigger after the deer has left the scene."

Bloom and his neurologist peer at UVA Health, Dr. Anelyssa D'Abreu, talked to UVA Today about Donanemab and the nature of Alzheimer's, as well as about why looking at an increasingly younger target audience may be worthwhile.

Donanemab: Where's the Data?

"So far we only have the press release. The data has not been published," said D'Abreu, an assistant professor of neurology in the School of Medicine who specializes in geriatrics. "So, it is hard to completely understand all the findings."

Donanemab isn't a pill, but rather a monoclonal antibody, which is a targeted therapy derived from one parent cell. You may have heard of monoclonal antibodies in regard to cancer treatment or as a COVID-19 therapy. The therapy is delivered as a blood infusion.

In the case of Donanemab, the target is the protein that makes up amyloid plaques. These misfolded proteins bunch up between nerve cells, disrupting cognition, which eventually leads to the death of neurons in the brain.

"The exciting result is that the drug slowed down the progression of the disease when compared to placebo," D'Abreu said. "The concerning issue is the side-effect profile."

Swelling of the brain occurred in about a fourth of the experimental group, with about a fourth of those patients experiencing symptoms. Two patients died from abnormalities attributable to the drug. A third died after having previously experienced brain abnormalities.

That doesn't mean the drug won't be approved, however. "It has a similar mechanism of action of Aducanumab and Lecanemab, two other Alzheimer's drugs that have received accelerated approval by the FDA," the doctor said.

Dr. Anelyssa D'Abreu is a UVA Health geriatric neurologist and an assistant professor in the School of Medicine. She is optimistic about the drug, though like many others, would like to see more data. (UVA Health photo)

So far, Lilly has held its data on Donanemab close to the vest, apparently for competitive reasons, the UVA experts said.