Aortic valve stenosis (AVS) is a significant health concern affecting over 1.5 million Americans and millions more globally. Researchers at Mayo Clinic are exploring the use of a new drug called ataciguat to manage AVS. Results from preclinical and clinical studies, published in Circulation, show that ataciguat has the potential to significantly slow disease progression. The final step to establish the drug's long-term effectiveness and safety is a phase 3 trial, and efforts to launch that pivotal trial are soon to be underway with an industry partner.

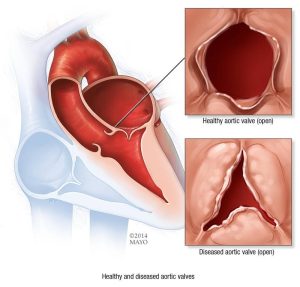

In AVS, calcium deposits build up and narrow the aortic valve, forcing the heart to work harder to move blood. The condition typically progresses over time, with symptoms like chest pain, shortness of breath and fatigue affecting people over age 65. The current standard of care - watchful waiting - often leads to reduced quality of life before the condition is severe enough for the patient to have a surgical or interventional valve replacement.

"This research represents a significant advancement in the treatment of aortic valve stenosis," says Jordan Miller, Ph.D., director of the Cardiovascular Disease and Aging Laboratory at Mayo Clinic. "Ataciguat has the potential to substantially delay or even prevent the need for valve replacement surgery, significantly improving the lives of millions."

Dr. Miller notes that the impact extends beyond simply delaying surgery. Younger patients with aggressive disease or congenital valve defects may develop symptoms in midlife. If a patient requires valve replacement before the age of 55, there is a more than 50% likelihood they will require multiple valve replacement surgeries over their lifetime due to recalcification of the implanted valve. Ataciguat, which slowed progression of native aortic valve calcification in the clinical trial, offers the potential for a once-in-a-lifetime procedure if they can reach the age of 65. The older a patient is, the less likely the implanted valve is to calcify.

Over the past decade, Mayo Clinic's research revealed that ataciguat reactivates a pathway crucial in preventing valvular calcification and stenosis. Preclinical studies in mice showed that this drug substantially slowed disease progression even when treatment began after the disease was established.

Clinical trials in patients with moderate AVS demonstrated that once-daily ataciguat dosing was well tolerated, with minimal side effects compared to placebo. This latest phase 2 trial in 23 patients showed a 69.8% reduction in aortic valve calcification progression at six months compared to placebo, and patients receiving ataciguat tended to maintain better heart muscle function. Crucially, the research team confirmed that - despite its profound effect on slowing valve calcification - ataciguat did not negatively impact bone formation.

This important finding is the result of a collaborative effort between Mayo Clinic, the National Institutes of Health, the University of Minnesota, and Sanofi Pharmaceuticals. The research was conducted under an innovative academic-industry partnership grant administered by the National Center for Accelerating Translational Sciences and a Minnesota Biotechnology and Genomics Partnership grant.

Mayo Clinic and Dr. Miller have a financial interest in the intellectual property referenced in this news release. Mayo Clinic will use any revenue it receives to support its not-for-profit mission in patient care, education and research.