Researchers from the University of Houston have reported a new device that can both efficiently capture solar energy and store it until it is needed, offering promise for applications ranging from power generation to distillation and desalination.

Unlike solar panels and solar cells, which rely on photovoltaic technology for the direct generation of electricity, the hybrid device captures heat from the sun and stores it as thermal energy. It addresses some of the issues that have stalled wider-scale adoption of solar power, suggesting an avenue for using solar energy around-the-clock, despite limited sunlight hours, cloudy days and other constraints.

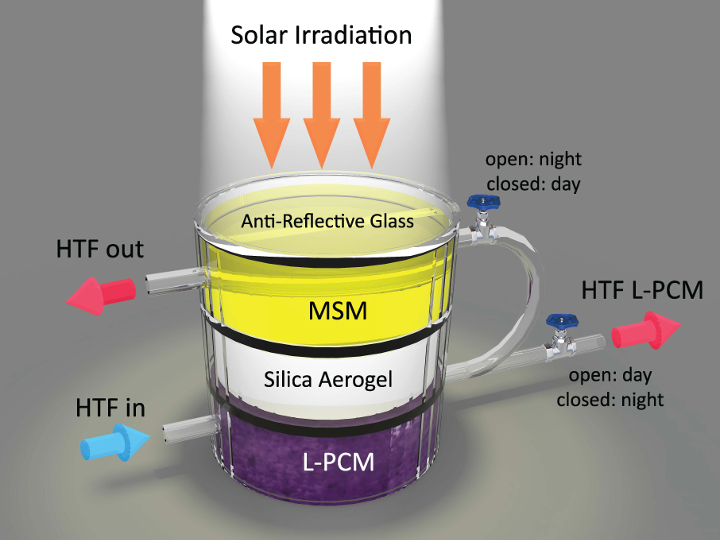

The work, described in a paper published Wednesday in Joule, combines molecular energy storage and latent heat storage to produce an integrated harvesting and storage device for potential 24/7 operation. The researchers report a harvesting efficiency of 73% at small-scale operation and as high as 90% at large-scale operation.

Up to 80% of stored energy was recovered at night, and the researchers said daytime recovery was even higher.

Hadi Ghasemi, Bill D. Cook Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering at UH and a corresponding author for the paper, said the high efficiency harvest is due, in part, to the ability of the device to capture the full spectrum of sunlight, harvesting it for immediate use and converting the excess into molecular energy storage.

The device was synthesized using norbornadiene-quadricyclane as the molecular storage material, an organic compound that the researchers said demonstrates high specific energy and exceptional heat release while remaining stable over extended storage times. Ghasemi said the same concept could be applied using different materials, allowing performance – including operating temperatures and efficiency – to be optimized.

T. Randall Lee, Cullen Distinguished University Chair professor of chemistry and a corresponding author, said the device offers improved efficiency in several ways: The solar energy is stored in molecular form rather than as heat, which dissipates over time, and the integrated system also reduces thermal losses because there is no need to transport the stored energy through piping lines.

"During the day, the solar thermal energy can be harvested at temperatures as high as 120 degrees centigrade (about 248 Fahrenheit)," said Lee, who also is a principle investigator for the Texas Center for Superconductivity at UH. "At night, when there is low or no solar irradiation, the stored energy is harvested by the molecular storage material, which can convert it from a lower energy molecule to a higher energy molecule."

That allows the stored energy to produce thermal energy at a higher temperature at night than during the day – boosting the amount of energy available even when the sun is not shining, he said.

In addition to Ghasemi and Lee, researchers involved with the work include first author Varun Kashyap, Siwakorn Sakunkaewkasem, Parham Jafari, Masoumeh Nazari, Bahareh Eslami, Sina Nazifi, Peyman Irajizad and Maria D. Marquez, all with UH.