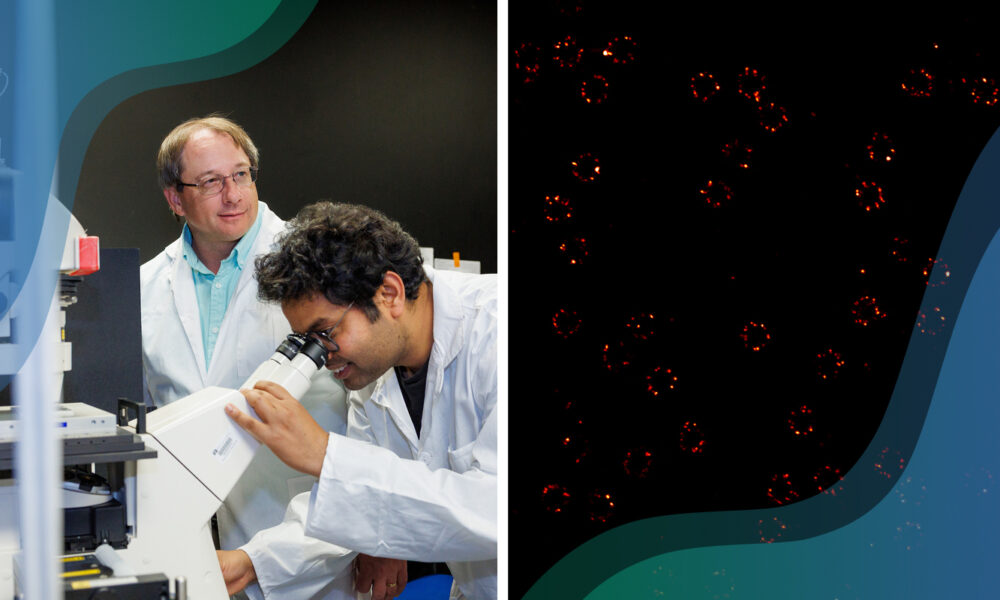

Texas A&M University researchers work with experts from EMBL Imaging Centre to uncover how molecules navigate the nuclear pore complex

Summary

- Cells must precisely coordinate how molecules pass in and out of the nucleus, similar to how a city regulates traffic to prevent traffic jams and collisions.

- New research from Texas A&M University has shed light on how molecules are imported and exported across the nuclear envelope, through structures known as nuclear pore complexes.

- The EMBL Imaging Centre supported the study with an advanced imaging method called MINFLUX, allowing researchers to precisely track this import/export process.

Just as cities must carefully manage the flow of cars in and out of downtown, cells regulate the movement of molecules in and out of the nucleus. This microscopic metropolis relies on intricate gateways - nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) - within the nuclear envelope - to control its molecular traffic. New research from Siegfried Musser's team at the Texas A&M University College of Medicine is shedding light on how this system operates with exquisite selectivity and control - discoveries that could lead to new insights into conditions such as neurodegenerative diseases and cancers.

Musser and his team have been investigating how molecules move through the pores of the double-membrane enveloping the nucleus quickly and efficiently without colliding or becoming congested. The team recently published a study in the journal Nature that revealed new insights into molecular transport.

The study required an advanced imaging technique called MINFLUX, which the EMBL Imaging Centre (IC) provided.

Using MINFLUX, the researchers tracked molecular movements in milliseconds and in 3D at an unprecedented scale: about 100,000 times smaller than the width of a human hair. Their findings show that import (the process of molecules entering the nucleus) and export (the process of molecules leaving) occur in overlapping highways within the nuclear pore complex. This challenges a previous hypothesis that these processes may take place in separate lanes.

A surprising traffic system

"When we started out, we considered two possibilities," Musser explained. "One, that import and export used distinct pathways, eliminating the risk of traffic jams; and two, that transport occurs through the same channel, but collisions were avoided as molecules manoeuvred around each other."

Their recent findings pointed to the second scenario. Molecules move through narrow conduits in both directions, weaving around one another rather than following a divided highway. Moreover, they only use a small cross-section of the pore diameter, migrating near the walls of the channel and absent from the centre. Even more surprisingly, movement within the NPC is about 1,000 times slower than in an open solution - like moving through maple syrup - due to a network of disordered proteins that occlude the pore.

"This is the worst-case scenario - two-way traffic in narrower conduits," Musser said. "What we discovered was an unexpected combination of these possibilities, so we actually don't know the full answer, and it's more complicated than we initially thought."

Avoiding gridlock

Despite the slow movement, NPC transport does not appear to be affected by crowding, seemingly successfully avoiding congestion.

"NPCs may be designed to be expressed in numbers such that they don't need to operate at capacity," Musser said. "This, in itself, could limit the deleterious effects of competition and clogging."

Rather than passing directly through the middle of the NPC, molecules seemingly move through one of eight distinct transport channels, each confined to a single spoke within the peripheral annulus, suggesting a structural mechanism that aids in traffic regulation.

"Yeast nuclear pores have long been observed to have a 'central plug,' but the nature of this material remains unknown," Musser said. "In humans, such a 'central plug' has not been readily observed, but functional compartmentalisation is a very real possibility and the pore centre could be the primary path of mRNA export."

Observing traffic jams on the nano-scale

To visualise the movement of molecules through the NPCs, the researchers needed a method that let them track individual molecules at high resolution across time. According to Sebastian Schnorrenberg, Application Specialist at the EMBL IC, MINFLUX is currently the light microscopy method that offers the highest spatial and temporal resolution, up to ten times more accurate for tracking than previous methods. It also allows researchers to track molecules significantly longer compared to other microscopy techniques.

"This meant we could obtain significantly more data points and achieve higher accuracy in tracking cargo molecules than was possible with previous technologies," said Schnorrenberg. While the Musser group previously published studies using conventional single-particle tracking methods, MINFLUX allowed them to analyse the import/export process much more precisely and provide new biological insights.

"On a personal level, it was one of the most technologically challenging user projects I have worked on," said Schnorrenberg. "During the course of the project, we had to solve various problems and develop new ways to combine different approaches, some of which we had never attempted before."

For processing and analysing the MINFLUX data, the researchers were supported by Ziqiang Huang, Image Analysis Specialist at EMBL IC. "MINFLUX provides the ability to track nuclear pore transport at nanometer spatial resolution and millisecond temporal resolution," said Huang.

"This project is also a great example of where we aim to develop our service in the EMBL IC long term," said Schnorrenberg. "MINFLUX not only enables the tracking of individual molecules in cells but could theoretically also be used to visualise structural changes in proteins, thus allowing us to observe proteins in action. I personally find this extremely exciting."

Implications for disease and future research

The NPC plays a crucial role in cellular function, and its dysfunction has been linked to numerous diseases, including progressive brain diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Alzheimer's disease and Huntington's disease. In addition, increased NPC trafficking rates are known to be important for cancerous growth. While targeting specific NPC regions might present a potential therapeutic strategy for unclogging 'blocked' pores or knocking down trafficking rates, Musser cautions that NPC transport is a fundamental cellular function, and interfering with various aspects of function could cause significant side effects.

"It is important to distinguish between effects that occur at the pore (transport) from effects that occur away from the pore (transport complex assembly and disassembly)," Musser said. "I suspect that most nuclear transport links to disease fall into the latter category, but this doesn't imply that all do, and some certainly do not." For example, mutations in the c9orf72 gene, which is associated with ALS and frontotemporal dementia, can lead to aggregates that block NPCs.

Looking ahead, Musser and his primary collaborator, Abhishek Sau, PhD, Assistant Research Scientist and Facility Manager for the Texas A&M Joint Microscopy Lab, will continue working with their team in Germany (EMBL IC and Abberior Instruments) to determine whether different cargo molecules - such as large ribosomal subunits and mRNA - use distinct transport pathways or share a common route. Also on the horizon is the possibility of adapting MINFLUX for real-time imaging in live cells, which could provide an even clearer picture of nuclear transport dynamics.

This study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, offers a new perspective on how cells efficiently manage molecular traffic, providing crucial insights into cellular function and disease. The nucleus may be a microscopic metropolis, but thanks to the NPC, its traffic control system remains remarkably efficient.

This article is adapted from a press release from Texas A&M University , authored by Joana Rocha.