Geologists have developed a new theory about the state of Earth billions of years ago after examining the very old rocks formed in the Earth's mantle below the continents.

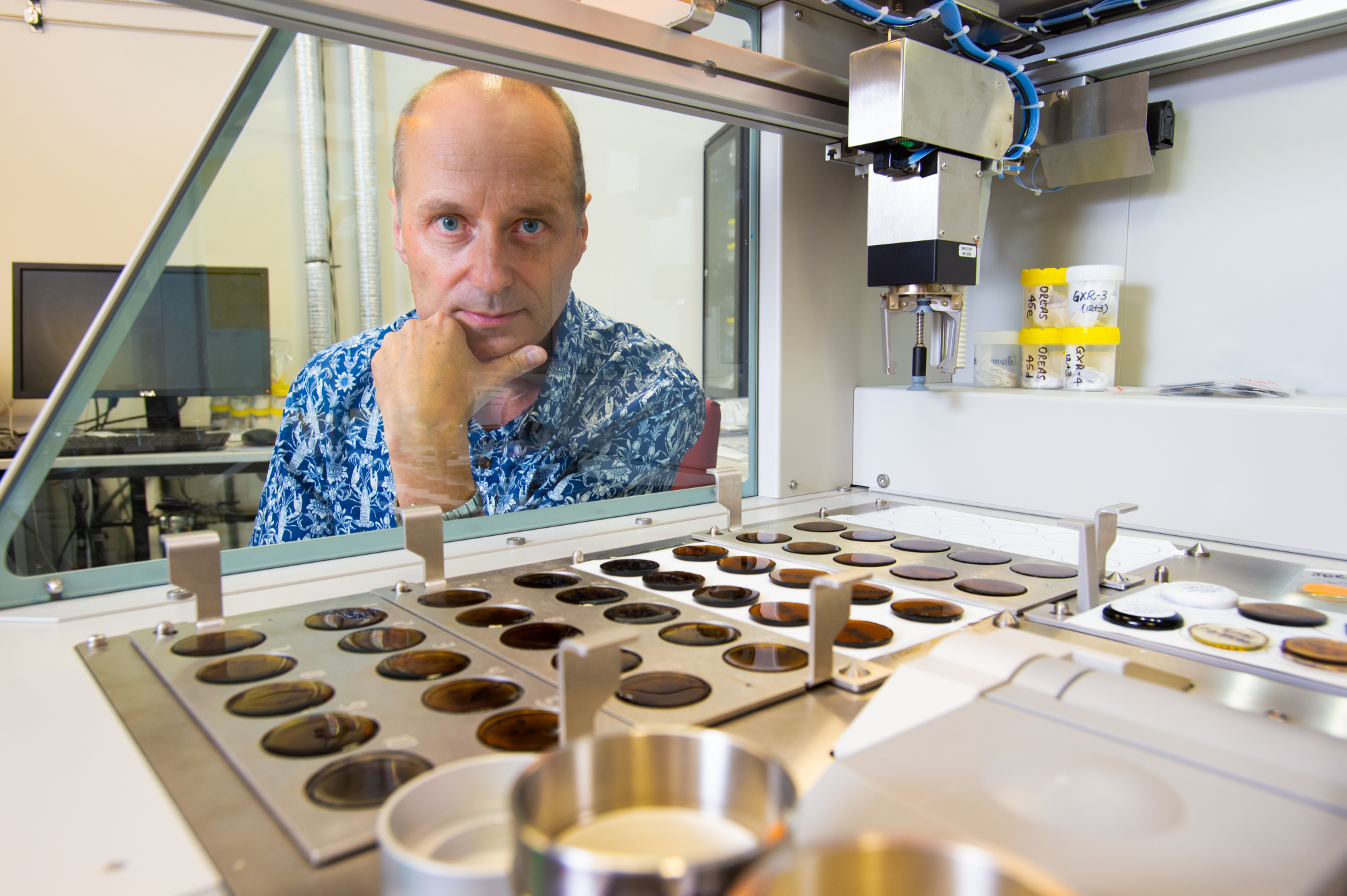

Assistant Professor Emma Tomlinson from Trinity College Dublin and QUT's Professor Balz Kamber have just published their research in leading international journal, Nature Communications.

The Earth's modern continents were built around a stable interior called a craton, and geologists believe that craton formation, some 2.5 - 3 billion years ago, was followed by the emergence of land masses. Little is known about how cratons and their supporting deep keels formed, but important clues can be found in ancient mantle samples. These samples of old mantle are available for study because volcanoes erupted them to the surface.

Dr Tomlinson said: "Many rocks from the mantle below old continents contain a surprising amount of silica – much more than is found in younger parts of the mantle.

"There is currently no scientific consensus about the reason for this."

The new research, which looks at the global data for old mantle peridotite, comes up with a new explanation for this observation.

Using the latest thermodynamic model, the research discovered that the unusual mineralogy developed when very hot molten rock - greater than 1700 degrees Celsius - interacted with older parts of the mantle. This caused silica-rich minerals to grow, some reaching many centimetres across, larger than in younger mantle.

"For more than 1 billion years, from 3.8 to 2.5 billion years ago, volcanoes also erupted very unusual lavas of very low viscosity – lava that was very thin, very hot and often contained variable levels of silica," Dr Tomlinson said.

Professor Kamber, from QUT's School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, said modelling suggested that the unusual lavas were in fact the molten rocks that interacted with the mantle at great depth and this interaction resulted in the variable level of silica.

"Both the silica-rich rocks in the deep mantle and the low viscosity volcanic rocks stopped being made by the Earth some 2.5 billion years ago. This timing is the boundary between the Archaean and Proterozoic eons – one of the most significant breaks in Earth's geological timescale," Professor Kamber said.

What caused this boundary remains unknown, but the research offers a new perspective.

"This may have been due to a change in how the mantle was flowing. Once the mantle started slowly turning over all the way down to the core (2900 km), the very high temperatures of the Archaean eon were no longer possible," Professor Kamber said.

The journal article, Depth-dependent peridotite-melt interaction and the origin of variable silica in the cratonic mantle, is available on request.